Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - begin learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

Linguistic reorganisation of States

1.0 Introduction

The integration of the princely states into the Indian Union produced a patchwork of different categories of state structures. The political units devised by 1950, in many cases, lacked economic viability or a suitable administrative machinery. The reorganisation of states came to the fore almost immediately. Language was made the basis of this reorganisation based on the Congress Party resolution of 1920 in Nagpur Session and its subsequent reaffirmation in 1927, 1937, 1938 and 1945-46.

In January, 1953 the All India Congress Committee at its Hyderabad session again adopted a resolution recommending the internal division of India primarily on a linguistic basis.

2.0 The States Reorganisation Commission

In December 1953, the Government of India appointed the States Reorganisation Commission to examine 'objectively and dispassionately' the problem of the reorganisation of States of the Indian Union.

The States Reorganisation Commission adopted a rational and balanced approach for the reorganisation of Indian states. Its mandate was:

- To recognise linguistic homogeneity as important factor but not to consider it as an exclusive and binding principle;

- To ensure that communicational, educational and cultural needs of different language groups are adequately met;

- Where satisfactory conditions exist, and the balance of economic, political and administrative considerations favour composite States, to continue them with the necessary safeguards to ensure that all sections enjoy equal rights and opportunities;

- To repudiate the 'home land' concept by upholding equal opportunities and equal rights for all citizens throughout the length and breadth of the Union;

- To reject the theory of 'one language one State' and finally,

- To the extent that realisation of unilinguism at State level would tend to breed a particularistic feeling, to counter balance that feeling by positive measures calculated to give a deeper content to Indian nationalism; to promote greater inter-play of different regional cultures, and inter- State cooperation and accord; and to reinforce the links between the Centre and the States in order to secure a greater coordinated working of national policies and programmes.

The Government of India examined this report in detail and proposed the reorganisation of India into 15 States and 7 Territories. Finally the Parliament passed the States Reorganisation Act, 1956 reorganising India into 14 States and 6 Union Territories from 1st November, 1956.

As result of this reorganisation, a very large area and population was brought under a similar administrative pattern. All States, covering 98 percent area and population of India, now had a similar judicial, legislative and executive structure as the chief components of the Republic. Only a small portion as the Union Territories was left under the Central guidance. The anomaly of the institution of Rajpramukh was removed, ending the last hereditary and feudal association with the administration as head of a State. The territorial contiguity was another major achievement.

Various blocks of territories, existing as enclaves and exclaves, even after the integration of States, were merged with the contiguous units; excepting the one anomaly in respect of Himachal Pradesh which was still left in two major blocks. Most of the reorganised States were larger in area and population than before; Madras and Bihar lost some areas while Assam, Orissa, Uttar Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir underwent no change. Certain former States like Hyderabad, Coorg, Bhopal, Saurashtra, Kachchh, Madhya Bharat, Vindhya Pradesh, Ajmer-Mewar and PEPSU lost their identities as such. All the Union Territories had the same boundaries as those existing before the Reorganisation.

There were very little boundary changes, old boundaries of different levels had been maintained. The number of States, as reorganised, was less than recommended by the Commission or proposed by the Government.

3.0 The Language Problem

The language problem was the most divisive issue in the first twenty years of independent India, and it created the apprehension among many that the political and cultural unity of the country was in danger. This controversy became most virulent when it took the form of opposition to Hindi and tended to create conflict between Hindi-speaking and non-Hindi speaking regions of the country. The issue of a national language was resolved when the Constitution-makers virtually accepted all the major languages as 'languages of India' or India's national languages.

However, the country's official work could not be carried on in so many languages. There had to be one common language in which the central government would carry on its work and maintain contact with the state governments. Only two languages were available for the purpose of official communication English and Hindi. The Constituent Assembly heatedly debated which one should be selected.

However, in fact, the choice had already been made in the pre-independence period by the leadership of the national movement, which was convinced that English would not continue to be the all-India medium of communication in free India.

Hindi or Hindustani, the other candidate for the status of the official or link language, had already played this role during the nationalist struggle, especially during the phase of mass mobilization. Leaders from non-Hindi speaking regions had accepted Hindi because it was considered to be the most widely spoken and understood language in the country. Lokamanya Tilak, Gandhiji, C. Rajagopalachari, Subhash Bose, and Sardar Patel were some of Hindi's enthusiastic supporters.

Sharp differences marked the initial debates as the problem of the official language. This question was highly politicized from the beginning. The question of Hindi or Hindustani was soon resolved, though with a great deal of acrimony. Gandhiji and Nehru both supported Hindustani, written in Devnagari or Urdu script. Though many supporters of Hindi disagreed, they had tended to accept the Gandhi-Nehru viewpoint. However, once Partition was announced, these champions of Hindi were emboldened, especially as the protagonists of Pakistan had claimed Urdu as the language of Muslims and of Pakistan. The votaries of Hindi now branded Urdu 'as a symbol of secession'. They demanded that Hindi in Devnagari script be made the national language. Their demand split the Congress party down the middle. In the end, the Congress Legislative Party decided for Hindi against Hindustani by 78 to 77 votes even though Nehru and Azad fought for Hindustani.

The case for Hindi basically rested on the fact that it was the language of the largest number, though not of the majority, of the people of India, it was also understood at least in the urban areas of most of northern India from Bengal to Punjab and in Maharashtra and Gujarat. The critics of Hindi talked about it being less developed than other languages as a literary language and as a language of science and politics.

However, their main fear was that Hindi's adoption, as the official language would place non-Hindi areas, especially South India, at a disadvantage in the educational and economic spheres, and particularly in competition for appointments in government and the public sector. Such opponents tended to argue that imposition of Hindi on non-Hindi areas would lead to their economic, political, social, and cultural domination by Hindi areas.

3.1 The Official Language Commission

In 1956, the Report of the Official Language Commission, set up in 1955 in terms of a constitutional provision, recommended that Hindi should start progressively replacing English in various functions of the central government with effective change taking place in 1965. Its two members from West Bengal and Tamil Nadu, Professor Suniti Kumar Chatterjee and

P. Subbarayan, however, dissented, accusing the members of the Commission of suffering from a pro-Hindi bias, and asked for the continuation of English. A special Joint Committee of the Parliament reviewed the Commission's Report. To implement the recommendations of the Joint Committee, the President issued an order in April 1960 stating that after 1965 Hindi would be the principal official language but that English would continue as the associate official language without any restriction being placed on its use. Hindi would also become an alternative medium for the Union Public Commission examinations after some time, but for the present, it would be introduced in the examinations as a qualifying subject. In accordance with the President's directive, the central government took a series of steps to promote Hindi.

All these measures aroused suspicion and anxiety in the non-Hindi areas and groups. Nor were the Hindi leaders satisfied.

In 1957, Dr Lohia's Samyukta Socialist Party and the Jan Sangh launched a militant movement, which continued for nearly two years, for the immediate replacement of English by Hindi. One of the agitational methods adapted by the followers of Lohia on a large scale was to deface English signboards of shops and in other places.

Lal Bahadur Shastri, Nehru's successor as prime minister, was unfortunately not sensitive enough to the opinion of non-Hindi groups. Instead of taking effective steps to counter their fears of Hindi becoming the sole official language, he declared that he was considering making Hindi an alternative medium in public service examinations. This meant that while non-Hindi speakers could still compete in the all-India services in English, the Hindi speakers would have the advantage of being able to use their mother tongue.

3.2 The agitation in South India

As 26 January 1965 approached, a fear psychosis gripped the non-Hindi areas, especially Tamil Nadu, creating a strong anti-Hindi movement. On 17 January, the DMK organized the Madras State Anti-Hindi Conference, which gave a call for observing 26 January as a day of mourning. Students, concerned for their careers and apprehensive that they would be outstripped by Hindi-speakers in the all-India services, were the most active in organizing a widespread agitation and mobilizing public opinion. They raised and popularized the slogan: 'Hindi never, English ever.' They also demanded amendment of the Constitution. The students' agitation soon developed into state-wide unrest.

The Congress leadership failed to gauge the depth of the popular feeling and the widespread character of the movement and instead of negotiating with the students, made an effort to repress it. Widespread rioting and violence followed in the early weeks of February leading to large-scale destruction of railways and other union property. So strong was the anti-Hindi feeling that several Tamil youth, including four students, burned themselves to death in protest against the official language policy. Two Tamil ministers, C. Subramaniam and Alagesan, resigned from the Union Cabinet. The agitation continued for about two months, taking a toll of over sixty lives through police firings.

The agitation forced both the Madras and the Union governments and the Congress party to revise their stand. They now decided to yield to the intense public mood in the South, change their policy, and accept the major demands of the agitators. The Congress Working Committee announced a series of steps which were to form the basis for a central enactment embodying concessions and which led to the withdrawal of the Hindi agitation. This enactment was delayed because of the Indo-Pak war of 1965, which silenced all dissension in the country.

In 1967, Indira Gandhi moved a bill to amend the 1963 Official language Act. The Lok Sabha adopted the bill on 16th December 1967 by 205 to 41 votes. The Act provided that the use of English as an associate language will continue in addition to Hindi for official work at the centre; and for communication between the Centre and non Hindi speaking states, English will continue till the non-Hindi states wanted it.

4.0 Tamil Nation and DMK

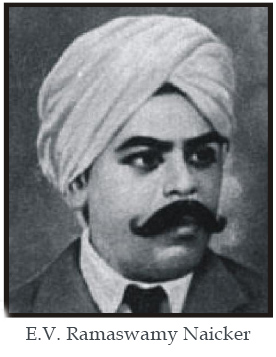

The DMK emerged in the fifties as a party and a movement that thrived on strong caste, regional, and even secessionist sentiments. It was the heir to two strands of the pre-independence period movements in Tamil Nadu : the non-Brahmin movement, which had led to the formation of the pro-British Justice party in 1920, and the strongly reformist anti-caste, anti-religion Self-Respect Movement led by E.V. Ramaswamy Naicker, popularly known as Periyar (Great Sage). In 1944, Naicker and C.N. Annadurai established Dravida Kazhagam (Federation) or DK which split in 1949 when Annadurai founded the Dravida Munnetra (Progressive) Kazhagam (DMK). But, significantly, in contrast to the Justice party and Naicker, Annadurai had taken up a strongly anti-imperialist, pro-nationalist position before 1947.

Annadurai was a brilliant writer, a skillful orator and an excellent organizer. Along with

M. Karunanidhi and M.G. Ramachandran (MGR) and other film personalities-actors, directors and writers-Annadurai used dramas, films, journals, pamphlets and other mass media to reach out to the people and over time succeeded in building up a mass base, especially among the youth with a rural background, and a vibrant political organization.

The DMK was strongly anti-Brahmin, anti-North and anti-Aryan- southern Brahmins and North Indians being seen as Aryans, all other South Indians as Dravidas. It raised the slogan of opposition to the cultural, economic and political domination of the South by the North. Naicker and others had earlier in 1938 organized a movement against the decision of the Congress ministry to introduce Hindi in Madras schools, labelling it to be an aspect of Brahmanical North Indian cultural domination. DMK also decided to oppose what it described as expansion of Hindi 'imperialism' in the South.

Its main demand, however, was for a homeland for the Dravidas in the form of a separate independent South Indian state-Dravidnadu or Dravidasthan- consisting of Tamil Nadu, Andhra, Karnataka and Kerala.

During the fifties and sixties, however, there were several developments that gradually led to a change in the basic political thrust of DMK. Naicker gave up his opposition to Congress when in 1954, Kamaraj, a non-Brahmin, displaced C. Rajagopalachari as the dominant leader of Congress in Tamil Nadu and became the chief minister.

DMK leadership too gradually lessened its hostility to Brahmins and started underplaying its anti-Brahmin rhetoric.

There was also a gradual change in DMK's secessionist plank as it began to participate in elections and in parliamentary politics. That a change was coming became visible when, in the 1962 elections it entered into an alliance with Swatantra and CPI and did not make a separate Dravidnadu a campaign issue though it was still a part of its manifesto. Later still, during the India-China war, it rallied to the national cause, fully supported the government, and suspended all propaganda for secession.

A further and final change came when, as a result of Nehru's determination to deal firmly with any secessionist movement, the 16th Constitutional Amendment was passed in 1962 declaring the advocacy of secession a crime and requiring every candidate to parliament or state assembly to swear 'allegiance to the Constitution' and to 'uphold the sovereignty and integrity of India.' The DMK immediately amended its Constitution and gave up the demand for secession. From secessionism it now shifted to the demands for greater state autonomy, more powers to the states, while limiting the powers of the central government, an end to the domination and unfair treatment of the South by the Hindi-speaking North, and allocation of greater central economic resources for the development of Tamil Nadu. It also further softened its anti-Brahmin stance and declared itself to be a party of all Tamils, which would accommodate Tamil Brahmins.

After Annadurai's death in February 1969, M. Karunanidhi became the chief minister. In 1972, the DMK split, with MGR forming the All-India Anna DMK (AIADMK). The two-party system now emerged in Tamil Nadu, but operated between the two Dravida parties, with both parties alternating in power in the state since then.

5.0 NORTH EASTERN UNION

Soon after India's independence, some of the Christian missionaries and other foreigners started promoting sentiment in favour of separate and independent states in north-eastern India. The virtual absence of any political or cultural contact of the tribals in the North-East with the political life of the rest of India was also a striking difference. The struggle for independence had little impact among the tribals of the North-East. To quote Jawaharlal Nehru: 'the essence of our struggle for freedom was the unleashing of a liberating force in India. This force did not even affect the frontier people in one of the most important tribal areas.' Again: 'thus, they never experienced a sensation of being in a country called India and they were hardly influenced by the struggle for freedom or other movements in India. Their chief experience of outsiders was that of British officers and Christian missionaries who generally tried to make them anti-Indian.'

The tribal policy of the Government of India, inspired by Jawaharlal Nehru was therefore even more relevant to the tribal people of the North-East. 'All this North-East border area deserves our special attention,' Nehru said in October 1952, 'not only the governments, but of the people of India. Our contacts with them will do us good and will do them good also. They add to the strength, variety and cultural richness of India.'

A reflection of this policy was in the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution, which applied only to the tribal areas of Assam. The Sixth Schedule offered a fair degree of self-government to the tribal people by providing for autonomous districts and the creation of district and regional councils, which would exercise some of the legislative and judicial functions within the overall jurisdiction of the Assam legislature and the parliament. The objective of the Sixth Schedule was to enable tribals to live according to their own ways. The Government of India also expressed its willingness to further amend the constitutional provisions relating to the tribal people if it was found necessary to do so with a view to promote further autonomy. However, this did not mean, Nehru clarified that the government would countenance secession from India or independence by any area or region, or would tolerate violence in the promotion of any demands.

Nehru's and Verrier Elwin's policies were implemented best of all in the North-East Frontier Agency or NEFA, which was created in 1948 out of the border areas of Assam. NEFA was established as a Union Territory outside the jurisdiction of Assam and placed under a special administration. From the beginning, the administration was manned by a special cadre of officers who were asked to implement specially designed developmental policies without disturbing the social and cultural pattern of the life of the people. As a British anthropologist who spent nearly all his life studying the tribal people and their condition wrote in 1967, 'A measure of isolation combined with a sympathetic and imaginative policy of a progressive administration has here created a situation unparalleled in other parts of India.'

NEFA was named Arunachal Pradesh and granted the status of a separate state in 1987. While NEFA was developing comfortably, and in harmony with the rest of the country, problems developed in the other tribal areas, which were part of Assam administratively. The problems arose because the hill tribes of Assam had no cultural affinity with the Assamese and Bengali residents of the plains. The tribals were afraid of losing their identities and being assimilated by what was, with some justification, seen to be a policy of Assamization.

Soon, resentment against the Assam government began to mount and a demand for a separate hill state arose among some sections of the tribal people in the mid-fifties. However, this demand was not pressed with vigour; nor did the Government of India encourage it, for it felt that the future of the hill tribes was intimately connected with Assam though further steps towards greater autonomy could be envisaged.

However, the demand gained greater strength when the Assamese leaders moved in 1960 towards making Assamese the sole official language of the state. In 1960, various political parties of the hill areas merged into the All Party Hill Leaders Conference (APHLC) and again demanded a separate state within the Indian union. The passage of the Assam Official Language Act, making Assamese the official language of the state, and thus the refusal of the demand for the use of the tribal languages in administration, led to an immediate and strong reaction in the tribal districts. There were hartals and demonstrations, and a major agitation developed. In the 1962 elections, the advocates of a separate state, who decided to boycott the State Assembly, won the overwhelming majority of the Assembly seats from the tribal areas.

Prolonged discussions and negotiations followed. Several commissions and committees examined the issue. Finally, in 1969, through a constitutional amendment, Meghalaya was carved out of Assam as 'a state within a state', which had complete autonomy except for law and order which remained a function of the Assam government. Meghalaya also shared Assam's High Court, Public Service Commission and Governor. Finally, as a part of the reorganization of the North-East, Meghalaya became a separate state in 1972, incorporating the Garo, Khasi and Jaintia tribes.

Simultaneously, the Union Territories of Manipur and Tripura were granted statehood. The transition to statehood in the case of Meghalaya, Manipur, Tripura and Arunachal Pradesh was quite smooth. Trouble arose in the case of Nagaland and Mizoram where secessionist and insurrectionary movements developed.

5.1 Nagaland

The Nagas were the inhabitants of the Naga Hills along the North-East frontier on the Assam-Burma border. They numbered nearly 500,000 in 1961, constituted less than 0.1 per cent of India's population, and consisted of many separate tribes speaking different languages. The British had isolated the Nagas from the rest of the country and left them more or less undisturbed though Christian missionary activity was permitted, and which had led to the growth of a small-educated stratum.

Immediately after independence, the Government of India followed a policy of integrating the Naga areas with the State of Assam and India as a whole. A section of the Naga leadership, however, opposed such integration and rose in rebellion under the leadership of A.Z. Phizo, demanding separation from India and complete independence. They were encouraged in this move by some of the British officials and missionaries. In 1955, these separatist Nagas declared the formation of an independent government and the launching of a violent insurrection.

The Government of India responded with a two-track policy in line with Jawaharlal Nehru's wider approach towards the tribal people. On the one hand, the Government of India made it clear that it would firmly oppose the secessionist demand for the independence of Naga areas and would not tolerate recourse to violence. Towards a violent secessionist movement, it would firmly follow a policy of suppression and non-negotiations. As Nehru put it, 'It does not help in dealing with tough people to have weak nerves.' Consequently, when one section of the Nagas organized an armed struggle for independence, the Government of India replied by sending its army to Nagaland in early 1956 to restore peace and order.

On the other hand, Nehru realized that while strong and quick military action would make it clear that the rebels were in a no-win situation, total physical suppression was neither possible nor desirable, for the objective had to be the conciliation and winning over of the Naga people. Nehru was wedded to a 'friendly approach'. Even while encouraging the Nagas to integrate with the rest of the country 'in mind and spirit', he favoured their right to maintain their autonomy in cultural and other matters. He was, therefore, willing to go a long way to win over the Nagas by granting them a large degree of autonomy. Refusing to negotiate with Phizo or his supporters as long as they did not give up their demand for independence or the armed rebellion, he carried on prolonged negotiations with the more moderate, non-violent and non-secessionist Naga leaders, who realized that they could not hope to get a larger degree of autonomy or a more sympathetic leader to settle with than Nehru.

In fact, once the back of the armed rebellion was broken by the middle of 1957, the more moderate Naga leaders headed by Dr Imkongliba Ao came to the fore. They negotiated for the creation of the State of Nagaland within the Indian union. The Government of India accepted their demand through a series of intermediate steps, and the State of Nagaland came into existence in 1963. A further step forward was taken in the integration of the Indian nation. In addition, politics in Nagaland since then followed, for better or worse, the pattern of politics in the other states of the union.

With the formation of Nagaland as a state, the back of rebellion was broken as the rebels lost much of their popular support. Though the insurgency has been brought under control, sporadic guerilla activity by Naga rebels trained in China, Pakistan, and Burma and periodic terrorist attacks continue till this day.

We may also refer to one other feature of the Naga situation. Even though the record of the Indian army in Nagaland has been on the whole clean, especially if the difficult conditions under which they operate are kept in view, it has not been without blemish. Its behaviour has been sometimes improper and in rare cases even brutal. Too many times innocent people have suffered. Then it has also paid a heavy price through the loss of its soldiers and officers in guerilla attacks.

5.2 Mizoram

A situation similar to that in Nagaland developed few years later in the autonomous Mizo district of the North-East. Secessionist demands backed by some British officials had grown there in 1947 but had failed to get much support from the youthful Mizo leadership, which concentrated instead on the issues of democratization of Mizo society, economic development and adequate representation of Mizos in the Assam legislature. However, unhappiness with the Assam government's relief measures during the famine of 1959 and the passage of the Act in 1961, making Assamese the official language of the state, led to the formation of the Mizo National Front (MNF), with Laldenga as president.

While participating in electoral politics, the MNF created a military wing, which received arms and ammunition and military training from East Pakistan and China. On March 1966, the MNF declared independence from India, proclaimed a military uprising, and attacked military and civilian targets. The Government of India responded with immediate massive counter-insurgency measures by the army. Within a few weeks the insurrection was crushed and government control restored, though stray guerilla activity continued. Most of the hardcore Mizo leaders escaped to East Pakistan.

In 1973, after the less extremist Mizo leaders had scaled-down their demand to that of a separate state of Mizoram within the Indian union, the Mizo district of Assam was separated from Assam and as Mizoram given the status of a Union Territory. Mizo insurgency gained some renewed strength in the late seventies but was again effectively dealt with by Indian armed forces. Having decimated the ranks of the separatist insurgents, the Government of India, continuing to follow the Nehruvian tribal policy, was now willing to show consideration, offer liberal terms.

A settlement was finally arrived at in 1986. Laldenga and the MNF agreed to abandon underground violent activities, surrender before the Indian authorities along with their arms, and re-enter the political mainstream of India.

The other state where an exception was made to the linguistic principle was Punjab. In 1956, the states of PEPSU had been merged with Punjab, which, however, remained a trilingual state having three language speakers - Punjabi, Hindi and Pahari - within its borders. In the Punjabi-speaking part of the state, there was a strong demand for carving out a separate Punjabi Suba (Punjabi-speaking state). Unfortunately, the issue assumed communal overtones. The Sikhs, led by the Akali Dal, and the Hindus, led by the Jan Sangh, used the linguistic issue to promote communal politics. While the Hindu communalists opposed the demand for a Punjabi Suba by denying that Punjabi was their mother tongue, the Sikh communalists put forward the demand as a Sikh demand for a Sikh state, claiming Punjabi written in Gurmukhi as a Sikh language.

Finally, in 1966, Indira Gandhi agreed to the division of Punjab into two Punjabi and Hindi-speaking states of Punjab and Haryana, with the Pahari-speaking district of Kangra and a part of the Hoshiarpur district being merged with Himachal Pradesh. Chandigarh, the newly-built city and capital of united Punjab, was made a Union Territory and was to serve as the joint capital of Punjab and Haryana.

6.0 Andhra Pradesh: The first linguistic state

The Andhras were struggling for the formation of a separate Andhra Province since the period of British, but could not succeed. When India attained Independence on the 15th of August, 1947, Andhras hoped that their long-cherished desire would be realised soon. Inspite of several renewed efforts put forth by the Andhra leaders before the Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and the Deputy Prime Minister Sardar Vallabhai Patel, the desire for a separate Andhra State remained as a dream itself.

The Dar Commission, appointed by the Government of India under the Chairmanship of S.K.Dar did not recommend for the creation of States on the linguistic consideration. This report of the Commission created such an adverse reaction in Andhra that the Congress leaders felt it prudent to assuage the ruffled feelings of the Telugus. An unofficial Committee, consisting of Jawaharlal Nehru, Vallabhbhai Patel and Pattabhi Sitaramaiah, popularly known as the J.V.P. Committee, was constituted by the Congress. The Committee in its report submitted to the Working Committee of the Indian National Congress in April, 1949 recommended that the creation of linguistic provinces be postponed by few years. However, it suggested that Andhra Province could be formed provided the Andhras gave up their claim to the city of Madras (now Chennai). This report provoked violent reaction in Andhra as the Telugus were not prepared to forego their claims to the city of Madras.

Under the prevailing situation, a Partition Committee was formed under the Chairmanship of Kumaraswami Raja, the then Chief Minister of Madras. Andhra was represented by Tanguturi Prakasam, B. Gopala Reddi, Kala Venkata Rao and N. Sanjiva Reddy. The Partition Committee could not arrive at an agreed settlement. Prakasam disagreed with the views of other members and gave a dissenting note. The Government of India, took advantage of the dissenting note of Prakasam and shelved the issue. To express the resentment of the Andhras, Swami Sitaram (Gollapudi Sitarama Sastry), a Gandhian, undertook a fast unto death, which created an explosive situation in Andhra. However, Swami gave up his 35-day fast on the 20th of September, 1951, on the appeal made by Vinoba Bhave. Nothing came out of this fast except the increasing distrust of the people of Andhra towards their own leaders and the Government of India.

In the First General Elections of 1952, Andhras expressed their resentment towards the Congress leaders by defeating them at the polls. Out of the 140 seats from Andhra in the Madras Legislative Assembly, the Congress could secure only 43, while the Communist Party of India bagged as many as 40 seats out of the 60 it contested. In the Madras Legislative Assembly itself, the Congress could secure only 152. The non-Congress members in the legislature, numbering 164, formed themselves into a United Democratic Front (U.D.F.) and elected T.Prakasam as their leader. But the Governor nominated C.Rajagopala Chari to the Legislative Council and invited him to form the ministry.

After Rajagopala Chari became the Chief Minister of the Madras State, he tried to divert the Krishna waters by constructing Krishna-Pennar Project for the development of the Tamil area. The Andhras agitated against this as they feared that the Project spelt ruin to Andhra. The Government of India appointed an expert Committee under the Chairmanship of A.N. Khosla, who pronounced that the project in its present form should not be proceeded with and suggested the construction of a project at Nandikonda (the site of the present Nagarjunasagar Project).

The report of the Khosla Committee vindicated the apprehensions of the Andhras regarding the unfriendly attitude of Rajagopala Chari's Government towards the Andhras. The desire of the Andhras to separate themselves from the composite Madras State and form their own State gained further momentum.

At this juncture, Potti Sriramulu a self-effacing Gandhian, began his fast unto death on the 19th of October, 1952 at Madras. Though the fast created an unprecedented situation throughout Andhra, the Congress leaders and the Government of India did not pay much attention to it.

On the 15th of December, 1952, Sriramulu attained martyrdom. The news of Sriramulu's death rocked Andhra into a violent and devastating agitation. The Government of India was taken aback at this popular upsurge. On the 19th December, 1952, Jawaharlal Nehru announced in the Lok Sabha that the Andhra State would be formed with the eleven undisputed Telugu districts, and the three Taluks of the Bellary district, but excluding Madras City. On the 1st of October, 1953, Andhra State came into existence. It consisted of the districts of Srikakulam, Visakhapatnam, East Godavari, West Godavari, Krishna, Guntur, Nellore, Chittoor, Cuddapah, Anantapur and Kurnool, and the taluks of Rayadurg, Adoni and Alur of the Bellary district. On the question of Bellary taluk, it was included in the Mysore State on the recommendation of L.S.Mishra Commission.

6.1 The beginnings of Telangana

The States Reorganisation Commission, with Syed Fazl Ali as the Chairman, set up by the Government of India in December 1953, heard the views of different organisations and individuals and was though convinced of the advantages of Visalandhra, favoured the formation of separate State for Telangana. This report of the S.R.C. led to an intensive lobbying both by the advocates of Telangana and Visalandhra. The Communists reacted sharply and announced that they would resign their seats in the Hyderabad Legislative Assembly and contest elections on the issue. In the Hyderabad Legislative Assembly, a majority of the Legislators supported Visalandhra.

The Congress High Command favoured Visalandhra and prevailed upon the leaders of the Andhra State and Telangana to sort out their differences, who, thereupon, entered into a `Gentlemen's Agreement'. One of the main provisions of the Agreement was the creation of a `Regional Council' for Telangana for its all round development. An enlarged State was created by merging nine Telugu speaking districts of Adilabad, Nizamabad, Medak, Karimnagar, Warangal, Khammam, Nalgonda, MahabubNagar and Hyderabad, into Andhra State with its eleven districts of Srikakulam, Visakhapatnam, East Godavari, West Godavari, Krishna, Guntur, Nellore, Chittoor, Cuddapah, Anantapur and Kurnool. This was named ‘Andhra Pradesh’ with its capital at Hyderabad.

It was inaugurated on the 1st of November, 1956 by Jawaharlal Nehru. Neelam Sanjiva Reddy became the first Chief Minister of Andhra Pradesh, who later rose to the position of the President of India. Burgula Ramakrishna Rao, last of the Chief Ministers of Hyderabad State was elevated to the Office of the Governor of Kerala. C.M. Trivedi continued to be the Governor of Andhra Pradesh.

Finally, the modern state of Telangana was formed on the second of June, 2014 with Hyderabad as its capital.

Demand for new states

Leading individuals in Indian Independence movement in 1920s, 30s and 40s

- Early life : Ram Manohar Lohia, one of India's greatest freedom fighters, was born on March 23, 1910. Following the footsteps of his father Hira Lal, a patriot and freedom fighter, it did not take long for Lohia to decide the course of his life. He had dedicated his life to the welfare of India and its march towards total independence.

- Congress Socialist Party : He joined the Congress Socialist Party (CSP), the left wing of the Indian National Congress, when it was founded in 1934. Lohia worked as a member of the executive committee and also edited the weekly journal.

- We don’t want to fight your war : His vehement protests against enrollment of Indians in the Royal Army during World War II landed him in jail in 1939 and again in 1940. During Gandhi's call of Quit India Movement, Lohia and his fellow CSP members, including Jayaprakash Narayan, put up resistance in stealth. For this, he was again jailed in 1944.

- In Germany : Lohia studied at Berlin University in Germany. During this time, he organised the Association of European Indians that would raise voice against British oppression in India.He was jailed for writing an article 'Satyagraha Now' in Gandhi's newspaper Harijan.

- Hind Kisan Panchayat : After Independence, Lohia founded an organisation called Hind Kisan Panchayat to help farmers with agricultural solutions. had also protested against the Portuguese government's policy of restricted speech and movement of natives in Goa. Lohia wanted to have Hindi as the official language of India after Independence. He had said, "The use of English is a hindrance to original thinking, progenitor of inferiority feelings and a gap between the educated and uneducated public. Come, let us unite to restore Hindi to its original glory." He led agitations in that cause, but Hindi did not succeed in it. Lohia wrote his PhD thesis paper on the topic of Salt Taxation in India, focusing on Gandhi's socio-economic theory.

- A great test of Free Speech : A great test of Free Speech : At the turn of the 1950s, Lohia was prosecuted for exhorting citizens not to pay their taxes! The applicable law was a colonial statute that prohibited the kind of speech that Lohia engaged in, and its constitutionality was challenged before the Supreme Court. The state argued that even something as harmless as a call not to pay taxes could be a “spark" that would one day set the country ablaze in the flames of revolution. The court rejected this argument. It held that the state must establish a “proximate" or “imminent" connection between speech and violence, and not merely rely upon hypotheticals, or remote possibilities. Lohia’s case is one of the most important free speech judgements in the Supreme Court’s history. It marked a decisive break with a jurisprudence that the court had developed in the 1950s. In various cases, the court had upheld pre-censorship of the press, the colonial Press Act and Section 295A of the Indian Penal Code (blasphemy law). The court drew a distinction between “active membership" and “passive membership". Defining “active membership" as the incitement to imminent violent action, the court held that anything short of that was protected by the constitutional guarantee of freedom of speech, expression and association. (Article 19(2) of the Constitution lists eight grounds on the basis of which the state can restrict the freedom of speech and expression. Four of these have to do not so much with the content of speech, or what words are said, but the consequences that speech might have, especially in promoting violence. These are “sovereignty and integrity of India", “security of the State", “public order" and “incitement to an offence". While Article 19(2) allows the state to restrict speech “in the interests of" these categories, it also insists that the restrictions must be “reasonable".) Dr. Lohia passed away in 1967, at the age of 57 years.

Dr. C. N. Annadurai, fondly called Anna by Tamilians, was a charismatic leader of modern India. Born on 15 Sept., 1909 into a weaving caste family in Kanchipuram, Annadurai became a school teacher and journalist before switching to politics. Anna was Chief Minister barely for two years (1967-69) but is still remembered for his qualities – simplicity, statesmanship, political acumen and concern for the poor and willingness for reconciliation.

- In his college days, Anna was exposed to the non-Brahmin politics of the Justice Party and drawn towards Justice Party headed by the radical thinker Periyar E.V. Ramasamy.

- One of the stalwarts of the Dravidian movement, Anna attacked Brahminism and ‘Aryan' values as the cause of Tamil political and cultural decadence.

- Anna founded the most famous Dravidian party, Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) - meaning Dravidian Progressive Conference, in the year 1949, after a fall out with his mentor Periyar over the idea of India and Dravida Nadu.

- A great orator, script writer, theatre personality and journalist, Anna skilfully channelized the agitation against imposition of Hindi the official language of India. In 1967, DMK's swept assembly polls thus ending Congress dominance in the state and Anna was sworn in as Chief Minister of Madras state. Notably, his cabinet was the youngest in India then.

- Annadurai is credited with renaming Madras state as Tamil Nadu in 1969. It was during his tenure as chief minister , the state assembly passed a bill renaming the state.

- He felt that “Since most schools in India taught English, why could it be our link language? Why do Tamils have to study English for communication with the world and Hindi for communications within India? Do we need a big door for the big dog and a small door for the small dog? I say, let the small dog use the big door too! All that is needed is the big door. Both the big and the small dog could use it!”

- Anna was not against the political unity of India but was a strong advocator for maximum autonomy to the States. The abdication of the secessionist demand in wake of the Chinese aggression in 1962 was another example of his political acumen.

- He served as 1st Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu for 20 days in 1969 and fifth, and last Chief Minister of Madras from 1967 until 1969 when the name of the state of Madras was changed to Tamil Nadu. He passed away in Feb. 1969.

- Muthuvel Karunanidhi served as the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu for five separate terms. He was declared leader of the DMK party in 1969 after the death of its founder- C N Annadurai.

- Born in 1924 in a small village, and changed his name from Dakshinamoorthy to M Karunanidhi, due to the influence of rationalist movements (not using God’s names). He was a long-standing leader of the Dravidian movement and ten-time president of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (Dravidian Progressive Federation) party. Before entering politics he worked in the Tamil film industry as a screenwriter.

- The DMK leader started Murasoli newspaper, which is now a weekly journal and the official organ of the DMK. Karunanidhi published six volumes of his autobiography- Nenjukku Neethi since 1975.

- He personally never lost any election he contested, ever since he won for the first time in assembly elections in 1951. He won all the 13 elections he contested in, the last being the 2016 general elections from Tiruvarur.

- In 1957, Karunanidhi was elected to the Tamil Nadu assembly from Kulithalai assembly and soon became the party treasurer and in 1962 became the deputy leader of opposition. When Annadurai passed away in 1969, Karunanidhi outsmarted all the others to emerge as the chief minister.

- Karunanidhi survived two major splits and held the party together at trying times when the DMK was out of power for 12-long years between 1977 and 1989.

- Karunanidhi contributed a lot to Tamil literature- with scores of poems, novels, plays, articles and communication tools propagating ideologies made him a natural choice and recipient of honorific title of Kalaignar or loosely translated – Scholar of Arts.

- Karunanidhi wrote numerous screenplays including Rajakumaari, Devaki, Thirumbi Paar, Naam, Manohara, Malaikkallan,Rangoon Radha, Kuravanji, Kaanchi Thalaivan, Thayillapillai and Poompuhar, Poomalai.

- He was an active participant in national politics, being friendly with all major leaders and parties. Karunanidhi died on 7 August 2018 at Chennai after a prolonged illness. He was indirectly implicated in the 2G scam, but nothing was proven against him.

- Better known as the historian of the Indian National Congress, Dr. Bhogaraju Pattabhi Sitaramayya was born on 24 December 1880 in a poor Andhra Niyogi Brahmin family and took his M.B. & C.M. degree in 1901 from the Madras Medical College. Soon after his education Sitaraimayya moved to Masulipatnam and set up practice as a physician.

- When the partition of Bengal happened in 1905, it sent a wave of protest throughout the country. The leaders of Masulipatnam including Sitaraimayya strove hard to awaken the national feelings of the people through the press and by organising lectures and Harikathas. The youthful Sitaraimayya was at first inclined towards extremism and became an admirer of the 'Lal-Bal-Pal' school (i.e. of Lala Lajpat Rai, Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Bipin Chandra Pal).

- He soon became a member of the Home Rule League of Dr Annie Besant and ultimately became a Gandhian. Sitaraimayya made Masulipatnam the centre of his activities. Here in 1919, he started, an English nationalist weekly, the Janmabhumi. The Janmabhumi continued functioning till 1930. At Masulipatnam he started the Andhra Bank.

- His association with the Indian National Congress goes back to his college days. In 1916 he became a member of the All India Congress committee and gave up his medical practice. Soon he was elected a member of the Congress Working Committee and continued in that position until 1948.

- On the issue of Dominion Status vs Complete Independence Sitaraimayya, like Jawaharlal Nehru, favoured the latter. He was elected President of the Andhra Purna Swarajya Sangam.

- In the Calcutta session of the Congress in 1928, he voted against the 'All Party Resumption' demanding Dominion Status. On the eve of the Salt Satyagraha campaign in March 1930, Dr Pattabhi toured the villages of the East Krishna district and spoke to the villagers about the campaign.

- He himself broke the Salt Law in April 1930 by leading a batch of volunteers to the sea-shore near Masulipatnam and making salt. He was arrested and sentenced to imprisonment for a year and a fine of Rs 1,100. In October 1933, he was again arrested while picketing a shop selling foreign cloth and sentenced to six months imprisonment and a fine of Rs 500.

- Towards the close of 1938 Gandhi ji nominated him for the Presidency of the Congress when there was a growing extremist wing in the Party, but he was defeated in the election (by Subhash Chandra Bose).

- When Gandhi ji launched his campaign of Individual Satyagraha in 1940 - 41, Sitaraimayya was chosen to participate in it. He was also arrested during the Quit India Movement. He was released in June 1945. In December 1946 he was elected to the Constituent Assembly from Madras to work on a new Constitution under the Cabinet Mission's Plan.

- In 1948, he was elected President of the Jaipur session of the Indian National Congress. He was the Governor of Madhya Pradesh from 1952 to 1957. He passed away on 17 December 1959. He was also a member of the JVP Committee - Jawahar / Vallabhbhai / Pattabhi - to look into the issue of linguistic reorganisation of states in independent India.

- Though Sitaraimayya was a popular Congress leader and held in high esteem by Gandhi ji, he did not hanker after office and did not take part in elections to the Provincial Assemblies or the Central Legislature. He took pleasure in working for the organisation and in writing and publishing books. His earliest publication was 'National Education' (1912), of which K. Hanumantha Rao was co - author.

- In the subsequent years he wrote and published 'Indian Nationalism' (1913), 'The Redistribution of Indian Provinces on a Linguistic Basis' (1916), 'Non-Cooperation' (1921), 'History of the Indian National Congress' (Vol. 1 appearing as the Golden Jubilee Volume in 1935 and Vol. 2 in 1947), and many more works.

- He passed away in 1959 at Hyderabad.