Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - begin learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

Integration of Princely States in India

1.0 Introduction

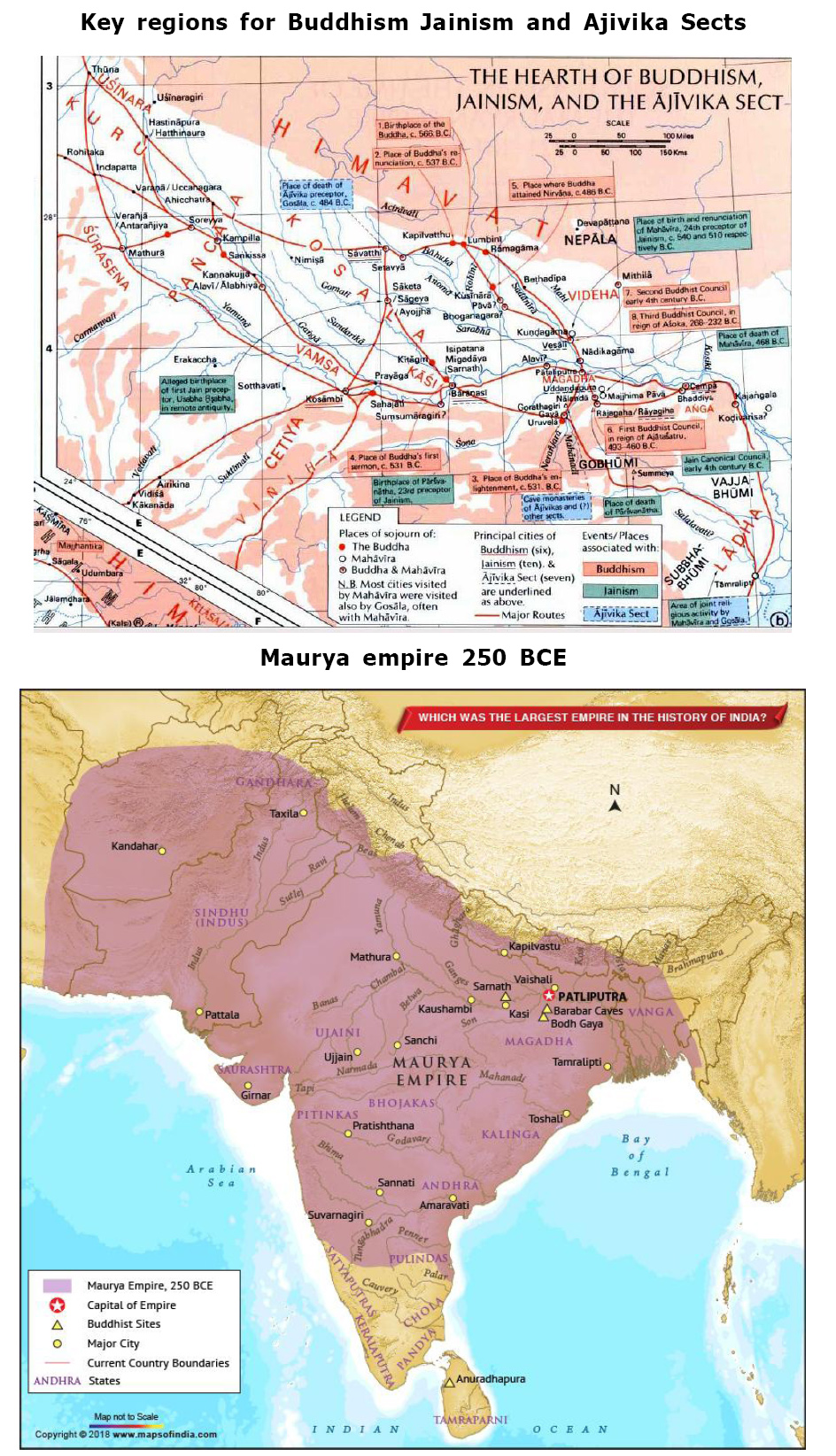

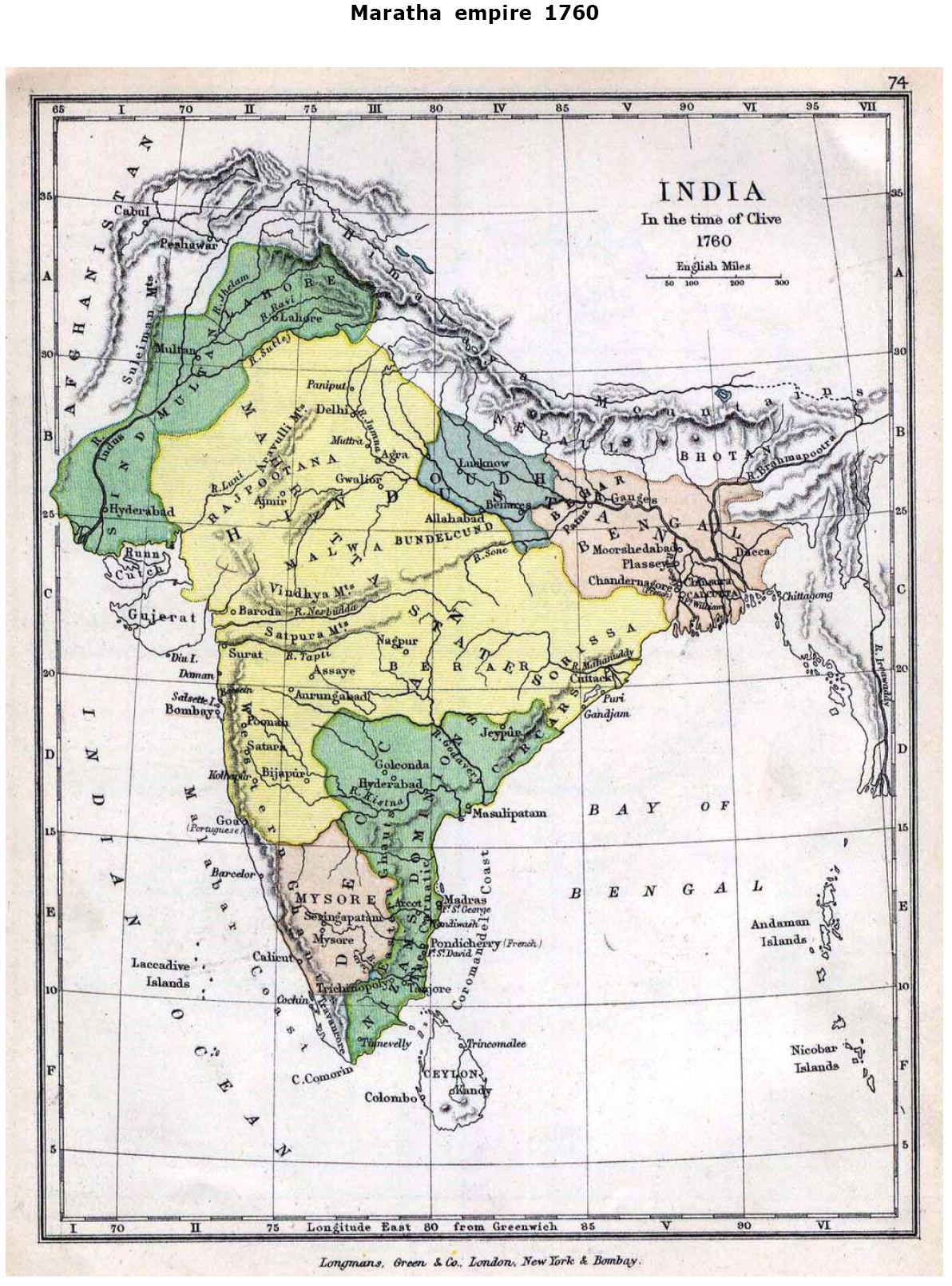

On the eve of Independence, the Indian country was divided into British India and the princely states. Two factors contributed to this. Since ancient times, India was divided into different provinces ruled by various dynasties. Only some rulers managed to bring a majority of India under their rule. On the eve of the Maurya Dynasty, India was divided into 16 mahajanapadas. From the time of Mauryas in ancient India till the time of the Mughals in medieval and modern India, the territories of various dynasties went through a continuous process of integration and fragmentation.

2.0 India under the British

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the British East India Company began acquiring large tracts of land in India through the conquest of the native kingdoms and principalities on one pretext or the other. The Subsidiary Alliance System of Wellesley had reduced many Indian States into a subordinate position vis-a-vis the Company. And quite a few of them were brought under the British rule by Dalhousie through the Doctrine of Lapse. The rest were controlled by the British through their residencies in these States. But when the Revolt of 1857 made it clear that the Indian princes were not happy with the dubious policy of the company, the British declared through the Queen's proclamation that there would be no further annexations and no interference in the internal affairs of any Indian State except in the case of gross mismanagement and disloyalty to the British crown. In 1876 during the Viceroyalty of Lord Lytton, the British queen was proclaimed as the Empress of India including the Indian States, and the British paramountcy in India was formally announced. Thus, by the second half of the 19th century the Indian subcontinent came to consist of the British India, ruled directly by the Viceroy, and a large number of princely states, ruled indirectly by the British.

2.1 Early Movements of people in States

The Movements of the people of these Indian States played a significant role in their final integration with the Indian Union. The origins of these movements could be traced to the numerous spontaneous local peasant uprisings against oppressive taxation in several princely states like Mewar, Kashmir, Travancore, Mysore, Hyderabad, etc., from the beginning of the 20th century. But all these peasant uprisings were violently suppressed by the rulers with the active support of the British. However, urban nationalism, in the form of urban middle class "prajaparishads" with nationalistic ideas, began emerging in the 1920s in most of the princely states, when Subjects' Conference (later renamed People's Conference) began to meet annually.

2.2 The All India State People's Conference (AISPC)

In order to stop the rising nationalist trend from spreading into the princely states, the British set up the Chamber of Princes in 1921. This was in tune with their general policy of divide and rule. In 1927 along with the appointment of the Simon Commission (meant for British India only), the British also appointed the Harcourt Butler Commission to recommend measures for the establishment of better relationships between the Indian states and the British Government. In response to this Government move, nationalists among the States' people, such as Balwantrai Mehta and Manik Kothari of Kathiwar and G.R. Abhyankar of the Deccan, convened an All-India States Peoples' Conference (AISPC) in December 1927, which was attended by 700 delegates from all over India. The aim of the AISPC was to influence the rulers of the Indian States to initiate the necessary reforms in the administration and to emphasise popular representation and self-Government in all of them. Further, AISPC stood for the establishment of constitutional relations between British India and the Indian States, and also an effective voice for the state's people in this relationship. This, in its opinion, would hasten the attainment of independence by the whole of India.

As a direct consequence of its stand that the Indian States should be treated as integral parts of the whole of India, the AISPC had requested the British Government to allow the people of states to be represented at the First Round Table Conference, which was, however, not permitted by the British. The AISPC then presented a memorandum to the Congress Party advocating an all-India federal Constitution in which all fundamental rights and privileges which the Karachi Session of the Congress (1929) had called for in British India would be accorded to the people of the states as well.

2.3 The Congress and the AISPC

Till the late 1930s, the Congress maintained a non-intervention stand towards the affairs of the Indian States. It felt that political activities in each state should be organised and controlled by the local Praja Mandal. It maintained that a movement which was started by people external to the princely states would not be successful. It was only in 1938 at its Haripura Session that the Congress included the independence of the princely states as well in its goal of Poorna Swaraj. At the same time, it insisted that for the time being it could only give its moral support and sympathy to states people's movements, which should not be conducted in the name of the Congress. The Tripuri Session (1939) took the logic ahead and decided that the organisation should involve itself closely with the movements in the princely states. Jawaharlal Nehru became the president of the AISPC in 1939 which was symbolic of the common national aims of political struggles in British India and the princely states. Thus the States Peoples Movements, besides awakening national consciousness among the people of the states, also spread a new consciousness of unity all over India.

3.0 The Princely states in the 1940s

The 1940s were a crucial phase in the Indian National movement. Due to the INA trials and RIN revolt, the movement had spread to hitherto unpoliticised areas. With the impending lapse of British paramountcy, the question of the future of the princely states became a vital one. The more ambitious rulers or their dewans were dreaming of an independence which would keep them as autocratic as before, and such hopes received considerable encouragement from the British Indian Government till Mountbatten followed a more realistic policy.

Meanwhile a new upsurge of the states people's movement had begun in 1946-47, demanding political rights and elective representation in the Constituent Assembly. The Congress criticized the Cabinet Mission Plan for insisting on nominees of the rulers instead of nominees of the people of the State. Nehru presided over the Udaipur and Gwalior Sessions of the AISPC (1945 & 47) and declared at Gwalior that the states refusing to join the Constituent Assembly would be treated as hostile. But verbal threats and speeches apart, the Congress leadership, or more precisely Sardar Patel tackled the situation very cleverly, using popular movements as a lever to extort concessions from princes while simultaneously restraining them or even using force to suppress them once the princes has been brought to heel, as in Hyderabad.

When the British decided to transfer power to Indians, they no doubt found it the best solution to a difficult problem to declare that the paramountcy which they exercised over the Indian states would automatically lapse. Thus, the edifice which the British themselves built up laboriously for more than 150 years was demolished overnight. But there were many Britishers conversant with the problem of the Indian states, who said at the time that the seriousness of the problem had not been appreciated at all by the British Government and that it was graver than any other that faced the country. Even in India there were very few who realised the magnitude of the threatened danger of balkanization. At the same time, there is no doubt that had paramountcy been transferred to a free India with all the obligations which had been assumed by the British Government under the various treaties, it would scarcely have been possible for us to have solved the problem of the Indian states in the way we did. By the lapse of paramountcy we were able to write on a clean state unhampered by any obligations.

4.0 Integration

Unifying post-Partition India and the princely states under one administration was perhaps the most important task facing the political leadership.

In colonial India, nearly 40 per cent of the territory was occupied by five sixty two small and large states ruled by princes who enjoyed varying degrees of autonomy under the system of British paramountcy. British power protected them from their own people as also from external aggression so long as they did British bidding.

In 1947 the future of the princely states once the British left became a matter of concern. Many of the large princely states began to dream of independence and to scheme for it. They claimed that the paramountcy could not be transferred to the new states of India and Pakistan. Their ambitions were fuelled by the British prime minister Clement Attlee's announcement on 20 February 1947 that ‘His Majesty's Government does not intend to hand over their powers and obligations under paramountcy to any government of British India’. Consequently, rulers of several states claimed that they would become independent from 15 August 1947 when British rule ended.

In this they got encouragement from M.A. Jinnah who publicly declared on 18 June 1947 that 'the States would be independent sovereign States on the termination of paramountcy' and were 'free to remain independent if they so desired.' The British stand was, however, altered to some extent when, in his speech on the Independence of India Bill, Attlee said, 'It is the hope of His Majesty's Government that the States will in due course find their appropriate place with one or the other Dominion within the British Commonwealth.'

The Indian nationalists could hardly accept a situation where the unity of free India would be endangered by hundreds of large or small independent or autonomous states interspersed within it which were sovereign. Besides, the people of the states had participated in the process of nation-in-the-making from the end of nineteenth century and developed strong feelings of Indian nationalism. Naturally, the nationalist leaders in British India and in the states rejected the claim of any state to independence and repeatedly declared that independence for a princely state was not an option-the only option open being whether the state would accede to India or Pakistan on the basis of contiguity of its territory and the wishes of its people.

In fact, the national movement had for long held that political power belonged to the people of a state and not to its ruler and that the people of the states were an integral part of the Indian nation. Simultaneously, the people of the states were astir under the leadership of the States Peoples' Conference as never before, demanding introduction of a democratic political order and integration with the rest of the country. With great skill and masterful diplomacy and using both persuasion and pressure, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel succeeded in integration the hundreds of princely states with the Indian Union. Some states had shown wisdom and realism and perhaps a degree of patriotism by joining the Constituent Assembly in April 1947. But the majority of princes had stayed away and a few, such as those of Travancore, Bhopal and Hyderabad, publically announced their desire to claim an independent status.

4.1 The States’ Department

On 27 June 1947, Sardar Patel assumed additional charge of the newly created States' Department with V.P. Menon as its Secretary. Patel was fully aware of the danger posed to Indian unity by the possible intransigence of the rulers of the states. He told Menon at the time that 'the situation held dangerous potentialities and that if we did not handle it promptly and effectively, our hard earned freedom might disappear through the States' door'. He, therefore, set out to tackle the recalcitrant states expeditiously.

Patel's first step was to appeal to the princes whose territories fell inside India to accede to the Indian Union in three subjects which affected the common interests of the country, namely, foreign relations, defense and communications. He also gave an implied threat that he would not be able to restrain the impatient people of the states and the government's terms after 15 August would be stiffer.

Fearful of the rising tide of the peoples' movements in their states, and of the more extreme agenda of the radical wing of the Congress, as also Patel's reputation for firmness and even ruthlessnessl the princes responded to Patel's appeal and all but three of them Junagadh, Jammu and Kashmir and Hyderabad acceded to India by 15 August 1947. By the end of 1948, however, the three recalcitrant states too were forced to fall in line.

4.2 Junagadh

Junagadh was a small state on the coast of Saurashtra surrounded by Indian territory and therefore without any geographical contiguity with Pakistan. Yet, its Nawab announced accession of his state to Pakistan on 15 August 1947 even though the people of the state, overwhelmingly Hindu, desired to join India.

The Indian nationalist leaders had for decades stood for the sovereignty of the people against the claims of the princes. It was, therefore, not surprising that in Junagadh's case Nehru and Patel agreed that the final voice, like in any other such case, for example Kashmir or Hyderabad, should be that of the people as ascertained through a plebiscite. Going against this approach, Pakistan accepted Junagadh's accession. On the other hand, the people of the state would not accept the ruler's decision. They organized a popular movement, forced the Nawab to flee and established a provisional government. The Dewan of Junagadh, Shah Nawaz Bhutto, the father of the more famous Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, now decided to invite the Government of India to intervene. Indian troops thereafter marched into the state. A plebiscite was held in the state in February 1948 which went overwhelmingly in favour of joining India.

4.3 Kashmir

The state of Kashmir bordered on both India and Pakistan. Its ruler Maharaja Hari Singh was a Hindu, while nearly 75 per cent of the population was Muslim. Hari Singh too did not accede either to India or Pakistan. Fearing democracy in India and communalism in Pakistan, he hoped to stay out of both and to continue to wield power as an independent ruler. The popular political forces led by the National Conference and its leader Sheikh Abdullah, however, wanted to join India. The Indian political leaders took no steps to obtain Kashmir's accession and, in line with their general approach, wanted the people of Kashmir to decide whether to link their fate with India or Pakistan. (Nehru and Patel had made a similar offer in the case of Junagadh and Hyderabad). In this they were supported by Gandhiji, who declared in August 1947 that Kashmir was free to join either India or Pakistan in accordance with the will of the people.

But Pakistan not only refused to accept the principle of plebiscite for deciding the issue of accession in the case of Junagadh and Hyderabad, in the case of Kashmir it tried to short circuit the popular decision through a shortsighted action, forcing India to partially change its attitude in regard to Kashmir. On 22 October, with the onset of winter, several Pathan tribesmen, led unofficially by Pakistani army officers, invaded Kashmir and rapidly pushed towards Srinagar, the capital of Kashmir. The ill trained army of the Maharaja proved no match for the invading forces. In panic, on 24 October, the Maharaja appealed to India for military assistance. Nehru, even at this state, did not favour accession without ascertaining the will of the people. Mountbatten, the Governor General, pointed out that under international law India could send its troops to Kashmir only after the state's formal accession to India. Sheikh Abdullah and Sardar Patel too insisted on accession.

And so on 26 October, the Maharaja acceded to India and also agreed to install Abdullah as head of the state's administration. Even though both the National Conference and the Maharaja wanted firm and permanent accession, India, in conformity with its democratic commitment and Mountbatten's advice, announced that it would hold a referendum on the accession decision once peace and law and order had been restored in the Valley.

After accession the cabinet took the decision to immediately fly troops to Srinagar. This decision was bolstered by its approval by Gandhiji who told Nehru that there should be no submission to evil in Kashmir and that the raiders had to be driven out. On 27 October nearly 100 planes airlifted men and weapons to Srinagar to join the battle against the raiders. Srinagar was first held and then the raiders were gradually driven out of the Valley, though they retained control over parts of the state and the armed conflict continued for months.

Fearful of the dangers of a full scale war between India and Pakistan, the Government of India agreed, on 30 December 1947, on Mountbatten's suggestion, to refer the Kashmir problem to the United Nation's Security Council, asking for vacation of aggression by Pakistan.

Nehru was to regret this decision later as, instead of taking note of the aggression by Pakistan, the Security Council, guided by Britain and the United States, tended to side with Pakistan. Ignoring India's complaint, it replaced the 'Kashmir question' before it by the 'India-Pakistan dispute'. It passed many resolutions, but the upshot was that in accordance with one of its resolutions both India and Pakistan accepted a ceasefire on 31 December 1948 which still prevails and the state was effectively divided along the ceasefire line. Nehru, who had expected to get justice from the United Nations, was to express his disillusionment in a letter to Vijaylakshmi Pandit in February 1948: ‘I could not imagine that the Security Council could possibly behave in the trivial and partisan manner in which it functioned. These people are supposed to keep the world in order. It is not surprising that the world is going to pieces. The United Sates and Britain have played a dirty role, Britain probably being the chief actor behind the scenes’.

In 1951, the UN passed a resolution providing for a referendum under UN supervision after Pakistan had withdrawn its troops from the part of Kashmir under its control. The resolution has remained infructous since Pakistan has refused to withdraw its forces from what is known as Azad Kashmir.

Since then Kashmir has been the main obstacle in the path of friendly relations between India and Pakistan. India has regarded Kashmir's accession as final and irrevocable and Kashmir as its integral part. Pakistan continues to deny this claim. Kashmir has also over time become a symbol as well as a test of India's secularism; it was, as Nehru put it, basic to the triumph of secularism over communalism in India.

4.4 Hyderabad

Hyderabad was the largest state in India and was completely surrounded by Indian territory. The Nizam of Hyderabad was the third Indian ruler who did not accede to India before 15 August. Instead, he claimed an in independent status and, encouraged by Pakistan, began to expand his armed forces. But, Sardar Patel was in no hurry to force a decision on him, especially as Mountbatten was interested in acting as an intermediary in arriving at a negotiated settlement with him. Time, Patel felt, was on India's side, especially as the Nizam made a secret commitment not to join Pakistan and the British government refused to give Hyderabad the status of a Dominion. But Patel made it clear that India would not tolerate 'an isolated spot which would destroy the very Union which we have built up with our blood and toil'.

In November 1947, the Government of India signed a stand still agreement with the Nizam, hoping that while the negotiations proceeded, the latter would introduce representative government in the state, making the task of merger easier. But the Nizam had other plans. He engaged the services of the leading British lawyer Sir Walter Monckton, a friend of Mountbatten, to negotiate with the Government of India on his behalf. The Nizam hoped to prolong negotiations and in the meanwhile build up his military strength and force India to accept his sovereignty; or alternatively he might succeed in acceding to Pakistan, especially in view of the tension between India and Pakistan over Kashmir.

Meanwhile, three other political developments took place within the state. There was rapid growth, with official help, of the militant Muslim communal organization, Ittihad ul Muslimin and its paramilitary wing, the Razakars. Then on 7 August 1947 the Hyderabad State Congress launched a powerful satyagraha movement to force democratization on the Nizam. Nearly 20, 000 satyagrahis were jailed. As a result of attacks by the Razakars and repression by the state authorities, thousands of people fled the state and took shelter in temporary camps in Indian territory. The state Congress led movement now took to arms. By then a powerful Communist led peasant struggle had developed in the Telangana region of the state from the latter half of 1946. The movement, which had waned due to the severity of state repression by the end of 1946, recovered its vigour when peasant dalams (squads) organized defence of the people against attacks by the Razakars, attacked big landlords and distributed their lands among the peasants and the landless.

By June 1948, Sardar Patel was getting impatient as the negotiations with the Nizam dragged on. From his sickbed in Dehradun, he wrote to Nehru: ‘I feel very strongly that a stage has come when we should tell them quite frankly that nothing short of unqualified acceptance of accession and of introduction of undiluted responsible government would be acceptable to us’. Still, despite the provocations by the Nizam and the Razakars, the Government of India held its hand for several months. But the Nizam continued to drag his feet and import more and more arms; also the depredations of the Razakars were assuming dangerous proportions. Finally, on 13 September 1948, the Indian army moved into Hyderabad. The Nizam surrendered after three days and acceded to the Indian Union in November. The Government of India decided to be generous and not punish the Nizam. He was retained as formal ruler of the state or its Rajpramukh, was given a privy purse of Rs. 5 million, and permitted to keep most of his immense wealth.

With the accession of Hyderabad, the merger of princely states with the Indian Union was completed, and the Government of India's writ ran all over the land. The Hyderabad episode marked another triumph of Indian secularism. Not only had a large number of Muslims in Hyderabad joined the anti Nizam struggle, Muslims in the rest of the country had also supported the government's policy and action to the dismay of the leaders of Pakistan and the Nizam. As Patel joyfully wrote to Suhrawardy on 28 September, 'On the question of Hyderabad, the Indian Union Muslims have come out in the open on our side and that has certainly created a good impression in the country.'

The second and more difficult stage of the full integration of the princely states into the new Indian nation began in December 1947. Once again Sardar Patel moved with speed, completing the process within one year. Smaller states were either merged with the neighbouring states or merged together to 'form’ centrally administered areas.' A large number were consolidated into five new unions, forming Madhya Bharat, Rajasthan, Patiala and East Punjab States Union (PEPSU), Saurashtra and Travancore Cochin; Mysore, Hyderabad and Jammu and Kashmir retained their original form as separate states of the Union.

In return for their surrender of all power and authority, the rulers of major states were given privy purses in perpetuity, free of all taxes. The privy purses amounted to Rs. 4.66 crore in 1949 and were later guaranteed by the constitution. The rulers were allowed succession to the gaddi and retained certain privileges such as keeping their titles, flying their personal flags and gun salutes on the ceremonial occasions.

There was some criticism of these concessions to the princes at the time as well as later. But keeping in view the difficult times just after independence and Partition, those were perhaps a small price to pay for the extinction of the princes' power and the early and easy territorial and political integration of the states with the rest of the country. Undoubtedly, the integration of the states compensated for the loss of the territories constituting Pakistan in terms of area as well as population. It certainly partially healed 'the wounds of partition'.

4.5 Pondicherry and Goa

Two other trouble spots remained on the Indian body politic. These were the French and Portuguese owned settlements dotting India's east and west coasts, with Pondicherry and Goa forming their hub. The people of these settlements were eager to join their newly liberated mother country. The French authorities were more reasonable and after prolonged negotiations handed over Pondicherry and other French possessions to India in 1954. But the Portuguese were determined to stay on, especially as Portugal's NATO allies, Britain and the US, were willing to support this defiant attitude. The Government of India, being committed to a policy of settling disputes between nations by peaceful means, was not willing to take military steps to liberate Goa and other Portuguese colonies. The people of Goa took matters in their hands and started a movement seeking freedom from the Portuguese, but it was brutally suppressed as were the efforts of non violent satyarahis from India to march into Goa. In the end, after waiting patiently for international opinion to put pressure on Portugal, Nehru ordered Indian troops to march into Goa as part of “Operation Vijay” on the night of 17 December 1961. The Governor General of Goa surrendered after a brief struggle and the territorial and political integration of India was completed, even though it had taken over fourteen years to do so.

Leading individuals in Indian Independence movement in 1920s, 30s and 40s

The Iron Man of India and Bismarck of India are titles lovingly given to one of the greatest freedom fighters of India, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. Starting his career as a barrister, Sardar Patel became an Indian independence activist later. Staging numerous protests against the English rule, he uprooted the tentacles of British administration. Despite several imprisonments, he remained resolute until the independence and final integration of the nation. Here are useful facts:

- Marriage and High School : At the age of 16, he got married to Jhaverba Patel in 1891 and at the age of 22, he passed his matriculation.

- Early ambition to be a Barrister : In his childhood, he made up his mind to be a barrister, and wanted to study in England. At that time, his family was not rich enough to enroll him in a college.

- Plague attack : When he was taking care of his friends suffering from the plague, Patel came down with the same disease. As the disease was highly contagious, Patel sent his family to a safe place and spent some time in a derelict temple. Later, he recovered from the disease slowly.

- Away from family : Patel spent several years away from family; studying on his own by borrowing books from friends. Later, he settled in Godhra with his wife.

- The making of a Barrister : Before going to England and becoming a barrister, Patel took a course in Law and practiced as a country-lawyer in Godhra, Borsad, and Anand.

- A genius mind : At the age of 36, Sardar Patel went to England to study Law. He enrolled in Middle Temple, Inns of Court, London. There, he completed his 36-months course within 30 months and topped his class despite having no college background.

- Dedicated to work : In 1909, his wife, Jhaverba Patel was admitted to hospital and diagnosed with cancer. Despite a successful surgery, she died in Hospital. When Patel was given a note of his wife’s death, he was cross-examining a witness in the court. Patel read the note and pocketed it and continued his work.

- A complete Englishman! When he returned from England, his lifestyle was changed, and he would wear suits and speak mostly in English. He used to smoke cigars at that time, but quit smoking later in the company of Mahatma Gandhi.

- An excellent Bridge player : He was fond of playing Bridge, a card game. In England as well as in India, he used to play and defeat many players of this game.

- A professional Barrister : When he returned to India in 1913, Patel settled in Ahmedabad and became one of the city’s most renowned barristers. He gained popularity as a criminal lawyer.

- Not a politician by choice : At the urging of his friends, he fought the municipal election in Ahmedabad in 1917 and won it.

- Inspiration from Gandhi : When Gandhi worked for the indigo-growing peasants, Patel was inspired a lot, and a subsequent meeting with Gandhi in 1917, changed Patel’s heart and led him to join the Indian independence movement.

- English suits in bonfire : After the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, Gandhi started the non-cooperation movement and Patel supported him thoroughly. Patel organized bonfires in various places of Ahmedabad and set all his English clothes and commodities on fire. He started wearing Khadi clothes.

- Round Table Conference : When the round-table conference failed in London, Sardar Patel along with Mahatma Gandhi was imprisoned in ‘Yeravda Central Jail’ in 1932. During that time, Patel became the right-hand man of Mahatma Gandhi. They both were released in July 1934. Gandhiji taught Patel Sanskrit during this time.

- First choice to be the President of Congress : During the 1946 Election for the Congress Presidency, 12 out of 15 regional congress committees proposed Patel to be the President. Despite the support of Mahatma Gandhi, no committee proposed Jawaharlal Nehru’s name. However, later, Patel stepped down in the favor of Jawaharlal Nehru.

- The Bismarck of India : Just like Otto von Bismarck integrated Germany politically in the 1860s, Vallabhbhai Patel unified India when the British paramountcy ended, by integrating more than 600 princely states into India, in an elaborate process lasting a few years, aided by V P Menon. During the time of integration, he was the first Commander-in-chief of the Indian Armed Forces.

- Political integration of India : The process of integration started once it was clear that the British would leave India. Sardar Patel began the work of convincing the Princes (Kings of hundreds of princely states) that they will not be harmed in any way (criminal prosecution, taking away of titles etc.) if they decide to join the Indian Union. A privy purse was also assured. Working tirelessly for many years, he led the States’ Department (headed by V P Menon) in this gargantuan project. Lord Mountbatten was also convinced to help integrate the state, to allow for continuity of many trade and commerce treaties that the British had evolved over the years. In an elaborate process, various documents were signed (including the Standstill Agreement and the two Instruments of Accession (1947 and 1948)) that ultimately led to a relatively smooth integration process, and a common Constitution for the entire India.

- Bharat Ratna : Due to his superb contribution to the unification of the nation, Sardar Patel was posthumously awarded the Bharat Ratna in 1991.

- National Unity Day : In 2014, the government of India announced that his birthday (31st October) will be celebrated as “National Unity Day” or “Rashtriya Ekta Diwas” in India.

- World’s tallest statue : In 2018, the Government of India unveiled the world’s tallest statue - The statue of Unity in Patel’s honor. The Prime Minister of India inaugurated this statue on Patel’s birthday, i.e., 31 October. The statue is made up of mostly bronze and designed by the famous sculptor, Ram V. Sutar.

- Early life : Hailing from a small village in Ottappalam, Vappala Pangunni Menon rose to be the highest ranking Indian official in the viceregal establishment. Posted as reforms commissioner, Menon held a key position, serving the last three viceroys as their constitutional adviser. In independent India, he served as secretary of the newly formed States’ Department and later as the governor of Odisha.

- An interesting incident : During his attempt to persuade the young Maharaja of Jodhpur to sign a provisional agreement of accession to the Indian Republic, Mountbatten left Menon to get young ruler’s signature. “When he was gone, the young maharaja of Jodhpur pulled a fountain pen made in his workshop out of his pocket. After signing the text, he unscrewed its cap and revealed a miniature 0.22 pistol which he pointed at Menon’s head. I’m not giving in to your threats, he shouted. Mountbatten, on hearing the noise, returned and confiscated the pistol,” stated Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre in their celebrated work Freedom at Midnight.

- More on early life and education : Loathed by Indian princes and nawabs, and trusted by the British and Indian authorities, Menon came from a humble family. Born on the banks of Bharatappuzha on September 30, 1893 at Panamanna in Ottappalam, he was the eldest son in a family of 12. At the age of 13, he had to quit school to work successively as a construction worker, coal miner, factory hand, stoker on Southern Indian Railways, unsuccessful cotton broker and schoolteacher. Finally, having taught himself to type with two fingers, he talked his way into a job as a clerk in the Indian administration in Shimla in 1929.

- With the Viceroy : “What followed was probably the most meteoric rise in that administration’s history. By 1947, Menon rose to one of the most-senior posts on the Viceroy’s staff, where he had quickly won Mountbatten’s confidence and later affection,” Collins and Lapierre wrote. In 1946, he was appointed as political reforms commissioner to British Viceroy.

- The plan : It was Menon who prepared the famous plan that led to India’s independence. In his book ‘Transfer of Power in India’, he recollected how he had only two or three hours to prepare an alternative draft plan. His plan was accepted by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and Mohammad Ali Jinnah.

- Political integration of India : Menon worked closely with Sardar Patel over the integration of over 500 princely states into the Union of India, applied diplomacy to foster good relations between the ministry and various Indian princes. He acted as Patel’s envoy and struck deals with reluctant princes and rulers to create the framework for present India. Patel respected his political genius and work ethic.

- Recognising him : “From 1945-50, Menon helped Patel annex over 500 princely states to independent India; more than what Bismarck did for Germany. There is not a single biography or a major biographical article in his name. His contributions don’t find a mention in school syllabus. There is only the V P Menon Award instituted in his memory at Ottappalam, which has produced many famous bureaucrats and diplomats,” said chairman of the award committee Rajasekharan Nair.

- Menon as an enabling architect of modern India : His character was such that he remained largely invisible. Sometime in 1965, Menon came to Ottappalam to inaugurate NSS’s BEd Training College and attended the function to honour Shankaran Nair who launched the movement for farmers’ rights.

- Death : A few months later, the able administrator of the British and independent India, died at Cooke Town in Cantonment, Bengaluru on December 31, 1965 aged 72.

- His early life and political involvement : Born in a humble family in Gujarat, on 19th Feb 1900, Balwantrai Gopalji Mehta as a child was a person of humility and well-disciplined. During his schooling days he displayed dedication towards studies and an interest in social welfare. At the age of 20, after graduation, he refused to earn further degree from foreign universities and joined the non-co-operation movement in 1920.

- Various movements : As a young graduate from a middle class family and a rigorous aspirant to the cause of India's independence, he was an active frontrunner in Civil Disobedience, Bordoli Satyagraha, and was imprisoned in 1942 for his participation in Quit Indian Movement, for 4 years.

- Mahatma Gandhi’s vision : His fidelity to the vision of M.K. Gandhi and for his relentless service to the country, Gandhi later recommended him for INC membership when India was freed from the foreign dominion, and thus become the member of congress working committee and eventually become the general secretary of All India Congress Committee during the tenure of Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru as the then President. He became the second CM of Gujarat succeeding Jivraj Narayan Mehta in 1963 and died during his office in 1965 during the Indo-Pak war when a Beechcraft plane carrying him and his wife and six other was shot down by a Pakistani aircraft mistaken for a military aircraft.

- The awakening of decentralized democracy in India : He focussed on rural development – decentralized democracy. Soon after the 1957 general election, he was appointed as the chairman of a parliamentary committee called the Estimate Committee to thoroughly examine and implement the working of community development and national extension service. Under his able chairmanship, the committee submitted its report and recommendation of a well-established local self-governance vehicle known as Panchayati Raj Institute (PRI).

- The PRI takes shape : One of the major characteristic of this recommendation was the establishment of three tier system within the PRI i.e. Gram Panchayat at the village level, Panchayat Samiti at the block level, and Zila Parishad at the district level. Of the three tier structure of the PRI, the Zilla Parishad which consists of district level officers from every spectrum including special representation of women, collector, and representative of the ST&SC stood as the apex body.

- Mandatory and discretionary power of PRI : The 73rd Amendment Act which becomes constitutionally effective from April 1993 was passed by parliament in 1992 to strengthen the working of PRI and subsequently inducted Part IX to the Constitution of India. This Act renders constitutional shape and endowed machinery tools to Article 40 of the constitution. Article 40 of the Indian Constitution envisaged the 'organization of village Panchayats' and mandates that, 'the State shall take steps to organize village panchayats and endow them with such powers and authority as may be necessary to enable them to function as units of self-government'. The mandatory power and discretionary power has each distinct contrary. The former used the word "shall" in its provisions whereas the word "may" was used in the later.

- With respect : Given the huge growth that the PRI has enabled over the decades, Mr. Balwantrai Mehta is remembered as the 'Architect of Panchayati Raj' with great respect.

- Inheriting a State : Maharaja Hari Singh inherited the vast state of Jammu Kashmir comprising of the Jammu Province, Jägirs of Poonch and Chenani, Province of Kashmir and Frontier Provinces of Ladakh, Baltistan and Gilgit. The credit of consolidating a vast territory and the founding of the state rests upon the vision of the warrior and statesman, Maharaja Gulab Singh, the great-grandfather of Maharaja Hari Singh.

- Last Dogra monarch : Maharaja Hari Singh was the fourth and the last Dogra monarch of the state. His rule from 1925 to 1947, saw a series of tumultuous historical events. His reign heralded a sea of reforms and people friendly policies which endeared him to all his subjects, irrespective of class, religion and gender.

- Changing times : Maharaja Hari Singh was sensitive to the changing times and made efforts to gradually democratise the administration. His Kingship was rooted in the concepts of social justice. His approach to governance was clear in his iconic coronation address where he said, “For me all communities, religions and races are equal. All religions are mine and justice is my religion”.

- A modern approach : He was a modern ruler devoted to the idea of eradicating illiteracy, social evils and inequality from the state. He was especially moved by the plight of the agriculturists of his state who formed eighty percent of the population. One of his first reforms, the Agriculturists Relief Regulations of July 1926, focused on freeing the farmers from the exploitative clutches of the moneylender. This was drafted in Uri in Kashmir, after the Maharaja who was camped there, received a thousand petitions on the same day against the Sahukari system. His reform aimed to empower the farmer and address the starvation and disease common amongst them due to their enslavement to the moneylending class. The cooperative credit system and an annual farmers conference where he could be apprised of the issues being faced by the farming community were all part of the many measures taken by the Maharaja for the upliftment of the majority class.

- Fighting illiteracy : To bring about socio-economic equality Maharaja Hari Singh put in concerted efforts in the drive against illiteracy, knowing very well that education was the biggest factor for social upward mobility. Progress in the field of education was across regions and the Maharaja particularly introduced Urdu as a medium of instruction to make it more attractive to his Muslim subjects. The Compulsory Primary Education Act of 1930 was put to immediate effect in Jammu, Srinagar, Sopore, Mirpur and Udhampur. The budget for education was raised from over rupees two lakhs in 1907 to nineteen and a half lakhs in 1931. As a result of this, there were 20,728 schools in 1945 as compared to 706 in 1925 when he took over from his predecessor.

- Progressive steps : Modern education and exposure made Maharaja Hari Singh committed to the cause of social equality which included women. He took many steps to remove gender-biased practices and elevated the status of women in the society. His measures focused on eradicating social evils like female infanticide and dowry. Polyandry which was prevalent in Ladakh was abolished in 1941. The Maharaja’s government not only enacted legislation to suppress immoral trafficking in women but made efforts for their reintegration in the society through rehabilitative schemes. The women were absorbed into respectable families and also trained in handicrafts.

- Women’s rights : Dhandevi Memorial Kanya Fund named after the Maharaja’s first wife granted orphan girls a sum of up to Rs 200 and an acre of state land. He was a tireless women’s rights champion encouraging widow remarriage and ownership of property by women. To ensure that women were included in the revolutionary changes being made in the field of education, he established the department of women education and appointed a Deputy Director for it. His many reforms in the health sector included women-centric measures like additional maternity wards in zenana hospitals.

- Controversial Act : To prevent Kashmir from becoming a British Colony, Maharaja Hari Singh introduced the Act of Hereditary State Subject in 1927 but the fact that he made no distinction in the definition and rights of the Permanent Residents of the state based on gender, is ignored today.

- Media freedom : A progressive ruler he believed in press freedom. Maharaja Hari Singh took steps to facilitate the publication of papers from Srinagar and Jammu bringing forth the Press and Publication Act in April 1932.

- A commitment to India : His commitment to India even as a ruler of a vast independent Princely state is noteworthy. He was the first amongst 560 rulers, who supported the cause of India’s Independence at the Round Table Conference in the House of Lords in London in 1931. He earned the wrath of British and an unsavoury saga of conspiracies unfolded against him upon his return to the state. Nevertheless, his words spoken in the House of Lords as Vice-Chancellor of Chamber of Prince’s rang loud and clear and should help in settling any doubts one may have of his loyalties. In the conference presided by the British Crown, he said: “I am an Indian first, and then a Maharaja”.

- End : Maharaja Hari Singh had to abdicate the throne unceremoniously with which ended the hundred years rule of the Dogra dynasty. He was forced into exile and was never to return to his beloved Jammu Kashmir. He was cremated in Chandanwadi in Mumbai and only his ashes returned home to be immersed in River Tawi.