Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - being learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

Colonial architecture Part I

1.0 Introduction

Leaving out the several European invasions upon India, of men who had left their impact in the country through lofty architectural styles, it was undoubtedly the British who have had a lasting impact on Indian architecture. The British viewed themselves as the successors to the mighty Mughals and used architectural style as a symbol of power. The colonialists had followed various styles within India. Some of the rather prestigious include: Gothic, Imperial, Christian, English Renaissance and Victorian.

The pomp, the vanity, the feeling of reigning supreme... all this the British transmuted into the buildings they erected in India. Colonial architectural style in British India wholly expressed the will of a people not simply to rule, evangelise, or exploit another but to adapt itself to alien circumstances, landscapes altogether unlike its own. It was because of the British mastery of technique that the British had an empire in India at all.

2.0 Evolution of the Colonial Architectural style

Colonial architectural style of India, the great period of their ascendancy in India, not surprisingly coincided almost exactly with their industrial pre-eminence in the world at large. Hence, the buildings they constructed in India were the direct reflection of their achievements back home. However, owing to long distance travels by sea, the architectural modes of England reached India rather late. The age of the Raj spanned several architectural periods. When the British first became a ‘power’ in India, the Palladian and the Baroque were the prevailing styles in England. Hence, the Britons established themselves in Bombay (presently Mumbai) during the construction of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Georgian neo-classicism was the overriding fashion in the years when they were developing the Presidency towns of Bengal, Madras and Bombay. By the time they had made themselves the paramount power throughout India, the Gothic revival was in full flair. The eclectic flamboyance of high Victorian coincided with their imperial zenith. During the decades that followed, the British gradually began further structural establishments in other places, henceforth making an everlasting impact upon colonial architectural style in India.

Colonial architectural style in India was severely hampered by the unpredictable Indian climate, an unfamiliar fact that the first British arrivals had to grapple with. Anglo-Indian architecture of all styles was accordingly mixed-up with devices against the weather. Rattan screens blocked its porticoes and verandahs. Shutters, hoods, lattice-work or Venetian blinds shaded its windows. Proportions had to be adjusted, layouts adapted, in response to the heat and the blazing light. The cleverer Anglo-Indian architects learnt, like the Mughals before them, to make vivid use of shade and shadow.

2.1 Features of the colonial architectural style in India

During the early years the Britons followed common Indian practices and built their houses of bamboo, or reeds plastered with earth and cow-dung, or mud bricks. The bricks were mostly sun-dried and renamed as cutcha. Pitched roofs were thatched at first, or tiled in rough clay. The early colonial architectural style of British India reflected flat roofs, which were often made of wood covered with tightly compacted layers of dried leaves and earth. Ceilings were of whitewashed hessian, giving rooms a limp and temporary air; balustrades were frequently of terracotta and in the absence of glass, oyster shells in wooden frames were sometimes utilised as windows. Good building materials were much in demand. In order to make a British construction astounding, sometimes the imperial builders had to import their materials, like marble from China, teak from Burma, gravel from Bayswater. Colonial architectures in Calcutta in the 1800s, and flagstones from Caithness for Bombay in the 1860s were perhaps the most prominent under this header, entrusting primary importance to these cities.

2.1.1 Usage of stone and iron

Colonial architectural style in British India witnessed another feature of rare usage of stone. This was in fact an everyday feature during the early days of the Empire and the church of St. John`s in Calcutta was simply called The Stone Church and the first house at Ootacamund (popular as Ooty) was also named Stone House. Later stone replaced brick as the prime material of British architectures in India; slate, machine-made tiles and steel girders came in vogue, and galvanised iron revolutionised the Anglo-Indian roof. Even as late as 1911, though, when the Britishers were planning a new Viceroy’s palace in Delhi, it was exhorted that for economy’s sake the building ought to be plaster-fronted.

2.1.2 Blissful anonymity

Another basic feature about colonial architectural style of India was that a majority of the constructions of British India were anonymous. English bricklayers had made an early appearance in the Presidency towns (comprising Bengal, Madras and Bombay) and the East India Company also had its own resident architects. Yet, from the beginning to the culmination of the British Empire, only a handful of eminent practitioners ever designed a building for the Raj. The stones of this empire were mostly put together by amateurs, and by soldiers who had learnt the building trade pro forma during their military education in England, or in later years by employees of the Public Works Department, established in 1854.

The early stages in British Empire witnessed mere amateurish works by carpenters, who were apparently architects to legendary buildings, like the first Writers Buildings in Calcutta. Britons of many other callings boldly undertook architectural works around places. In order to bring perfection in their works, often they relied upon handbooks of architectures, very popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Many of the grander early buildings of the Presidency towns owe their genesis to such texts. Colonial architectural style in British India in the 1830s relied heavily upon the invaluable works of John Loudon, whose several encyclopaedic textbooks offered models for almost every kind of building. Loudon`s texts probably had a greater influence than any others on the architecture of British India. However, during the more advanced and later stages, amateurism left the British Empire and the soldier-designers and engineers gave way to professional architects.

Colonial architectural style in British India was subtly but steadily taking giant strides towards manufacturing history. The Public Works Department, a virtuoso of the hybrid styles was established for this aim to train and govern masterpiece architectures. And when it came to the supreme commission of all, the design of the new capital of New Delhi in the first decades of the twentieth century, the job was entrusted to the two most famous colonial architects of the day, Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker.

2.2 The Progress (The Classical and the Gothic styles)

The first recognisable colonial architectural styles of British India were, in one sort or another, classical: this was the chosen mode of the East India Company until its dissolution and it was altogether deliberate. The British colonialists in India were evolving from traders to rulers and they welcomed a style that would so graphically express their cool superiority and historical antecedents (referring to the illustrious Mughal Dynasty). The eighteenth-century victories in the field that led to British supremacy in India powerfully boosted this lofty self-image. The British buildings of Calcutta and Madras seemed to speak of a civilisation self-sufficient and unshakeable till the end of time. The colonial architectural style in British India was meant to emphasise a lesson. The Whites were determined to demonstrate the superiority of their own ways, both for their own security and for the attention of the natives.

When they took Delhi in 1803, the British commandeered a fine local palace, built in the Mughal style, to be their Residency in the city. To this grand architectural wonder, they had affixed to its facade a grand colonnade of Ionic columns, setting their style and stamp upon it for all to see. Many a classical architectural device contributed to such forceful endings. Colonial architectural style in British India heavily borrowed from triumphal arches, toga’d statues, trophy halls and Pantheons. The traditional orders, Corinthian, Ionic, Tuscan and Doric, provided early British architects with useful allegories. During the hullabaloo of such overlapping architectures and buildings, presently, the Gothic fashion crept in. The forms of neo-classicism went out of fashion.

The first signs of Gothic indeed, stemming from the romantic Strawberry Hill, London kind, were to be seen in Madras and Calcutta at the end of the eighteenth century, like a Gothic chapel, with pepper-pot turrets and flying buttresses, which were surprisingly provided for Calcutta’s Fort William in 1784. But the approach of true Victorian Gothic was most clearly announced by the design of Calcutta Cathedral, the metropolitan church of British India, which was completed in 1847. Later to be popular as St. Paul’s Cathedral, it stood out as a magnificent mixture of the medieval and the antique specified by its Bishop as being ‘the Gothic or rather Christian style of architecture’. Gothic architectural style, thus, became the British idiom above all others. For one thing, it was cheaper to build than classical, so that there could be two evangelistic churches for the price of one; for another, it possessed none of the heathen implications of classical forms; and for a third, Gothic had the endorsement of all the best authorities at home: the Church Commissioners, the Camden Society, and The Ecclesiologist. The Anglo-Indian church designers quickly got the point.

2.2.1 End of the East India Company & rise of secular architecture

Next in line to the highly-progressive colonial architectural style in British India was secular architecture, which soonfollowed suit. Actually Gothic was far less suitable to the native environment than the classical styles. When Gothic pattern was transferred to the East, there was something close and restless to the very look of it. Another change of architectural style was signalled, after the Sepoy Mutiny (the first war of Indian independence 1857), by the culmination of the British East India Company’s pursuits in India. Queen Victoria and Her Majesty’s Crown now established its own administration for India. The Company’s Governor-General became the Queen’s Viceroy, Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India. For the first time a few Indians were admitted to the higher echelons of their own Government. Flamboyant new elements entered the imperial philosophy; it was an unusual time that the British began to introduce Indian features and motifs into their imperial architecture.

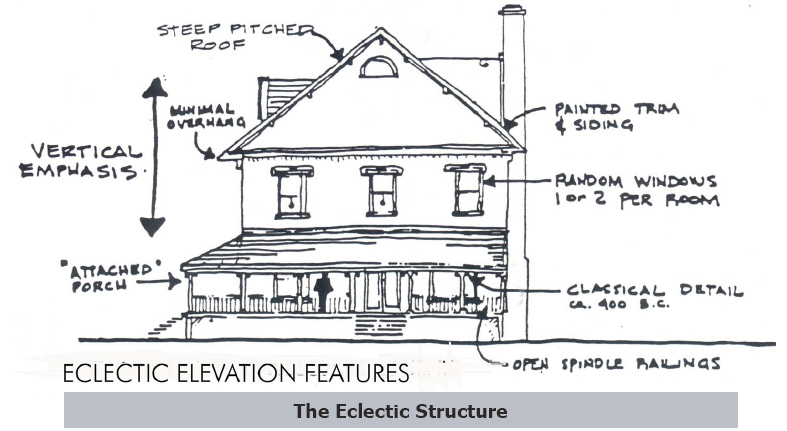

With time a hybrid style evolved in the colonial architecture. Eclecticism was, however, rampant enough. Fortunately for the architects the Gothic style, with its natural plethora of ornament, its pointed arches and vaulted roofs, lent itself reasonably easily to orientalisation; all manner of Eastern fancies invaded the orthodox architectural expressions. And the forms of the Northern masons found themselves metamorphosed with domes, kiosks and harem windows. ‘Indo-Saracenic’ was enigmatically the favourite generic name for these combinations, but the Hindu-Gothic, the Renaissance-Mughal, the Saracenic-Gothic, even the Swiss-Saracenic, were all identified at some time or another as architectural styles in British India. At times the British erected buildings in a wholly Indian way and in late-Victorian times there arose a vigorous ‘back-to-India’ movement among more imaginative Anglo-Indians. Hybrid buildings remained predominant, however, into the twentieth century.

In British India as in England, there was a return to simpler modes in the early twentieth century, with a flush of imperial certainty, as of Victorian complacency, fading away into battles and disillusionments. Colonial architectural style in India was anything but avant-garde and never really had time to absorb art nouveau. The genre, like the empire that gave it birth, went out gently, even apologetically in the end. Eclecticism was given a last fillip by the establishment of New Delhi, the new capital of India, between 1911 and 1932. However this eclecticism was of a more muted kind. Styles and symbol, Muslim, Buddhist, Christian and pagan, were somewhat cautiously blended in this last and greatest creative enterprise. There was a circular Parliament being built on Roman lines, a shopping centre evidently inspired by Bath (a town in south-western England on River Avon; legendary for its hot springs and Roman remains) or Regent Street and a presiding dome evolved from a Buddhist stupa.

Mild reflections of this vision floated across the subcontinent, to be solidified here and there in Sir Edwin Lutyens’s favourite upturned domes, or Baker’s Persian-like pavilions. In general, though, British India bowed itself out in an unmemorable insipidness of the neo-classical. Colonial architectural style of British India thus had encapsulated within itself enormous structural fashions, only to be still remembered in a mixed feel of awe and wonder.

3.0 Some famous monuments

The colonial influence can be seen in office buildings. Europeans who started coming from sixteenth century AD constructed many churches and other buildings. Portuguese built many churches at Goa, the most famous of these are Basilica Bom Jesus and the church of Saint Francis. The British also built administrative and residential buildings which reflect their imperial glory. Some Greek and Roman influence can be observed in the colonnades or pillared buildings. Parliament House and Connaught Place in Delhi are good examples. The architect Lutyens designed the Rashtrapati Bhavan, formerly the Viceroy's residence. It is built of sandstone and has design features like canopies and jaali from Rajasthan. The Victoria Memorial in Calcutta, the former capital of British India, is a huge edifice in marble. It now houses a museum full of colonial artefacts. Writers' Building in Calcutta, where generations of government officers worked in British times, is still the administrative centre of Bengal after independence. Some Gothic elements can be seen in the church buildings like St. Paul's Cathedral in Calcutta. The British also left behind impresive railway terminals like the Victoria Terminus in Mumbai.

More contemporary styles of building are now in evidence, after Independence in 1947. Chandigarh has buildings designed by the French architect, Corbusier. In Delhi, the Austrian architect, Stein, designed The India International Centre where conferences are held by leading intellectuals from all over the world and more recently, the India Habitat Centre which has become a centre of intellectual activities in the capital.

In the past few decades, there have been many talented Indian architects, some trained in premier schools of architecture like the School of Planning and Architecture (SPA) in Delhi. Architects like Raj Rewal and Charles Correa represent this new generation. Mr Raj Rewal has designed the SCOPE Complex and Jawahar Vyapar Bhavan in Delhi. He takes pride in using indigenous building material like sandstone for construction and also combines steps and open spaces from the plazas of Rome. An example of this is the CIET building in Delhi. Charles Correa from Mumbai designed the LIC Building in Connaught Place, Delhi. He has used glass facades in the high-rise to reflect light and create a sense of soaring height.

In domestic architecture in the last decade, Housing Cooperative Societies have mushroomed in all metropolitan cities combining utility with a high level of planning and aesthetic sense.