Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - being learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

The first Battle of Panipat,

& dawn of the Mughals - Part 2

4.0 Humayun's Conquest of Gujarat and his Tussle with Sher Shah

Humayun succeeded Babur in December 1530 at the young age of 23. He had to grapple with a number of problems left behind by Babur. The administration had not yet been consolidated, and the finances were precarious. The Afghans had not been subdued, and were nursing the hope of expelling the Mughals from India. Finally, there was the Timurid legacy of partitioning the Empire among all the brothers. Babur had counselled Humayun to deal kindly with his brothers, but had not favoured the partitioning of the infant Mughal Empire, which would have been disastrous.

When Humayun ascended the throne at Agra, the Empire included Kabul and Qandhar, while there was loose control over Badakhshan beyond the Hindukush mountains. Kabul and Qandhar were under the charge of Humayun's younger prother, Kamran. It was only natural that they should remain in his charge. However, Kamran was not satisfied with these poverty-stricken areas. He marched on Lahore and Multan, and occupied them. Humayun, who was busy elsewhere, and did not want to start a civil war, had little option but to agree. Kamran accepted the suzerainty of Humayun, and promised to help him whenever necessary. Kamran's action created the apprehension that the other brothers of Humayun might also follow the same path whenever an opportunity arose. However, the granting of the Punjab and Multan to Kamran had the immediate advantage that Humayun was free to devote his attention to the eastern parts without having to bother about his western frontier.

Apart from these, Humayun had to deal with the rapid growth of the power of the Afghans in the east, and the growing power and sweep of Bahadur Shah, the ruler of Gujarat. At the outset, Humayun was inclined to consider the Afghan danger to be the more serious of the two. In 1532, at a place called Daurah, he defeated the Afghan forces which had conquered Bihar and overrun Jaunpur in eastern Uttar Pradesh. After this success, Humayun besieged Chunar. This powerful fort commanded the land and the river route between Agra and the east, and was known as the gateway of eastern India. It had recently come in the possession of an Afghan sardar, Sher Khan, who had become the most powerful of the Afghan sardars.

After the siege of Chunar had gone on for four months, Sher Khan persuaded Humayun to allow him to retain possession of the fort. In return, he promised to be loyal to the Mughals and sent one of his sons to Humayun as a hostage. Humayun accepted the offer because he was anxious to return to Agra. The rapid increase in the power of Bahadur Shah of Gujarat, and his activities in the areas bordering Agra, had alarmed him. He was not prepared to continue the siege of Chunar under the command of a noble since that would have meant dividing his forces.

Bahadur Shah, who was of almost the same age as Humayun, was an able and ambitious ruler. Ascending the throne in 1526, he first overran and conquered Malwa. He then turned to Rajasthan and besieged Chittor. Soon he reduced the Rajput defenders to a sad state. According to some later legends, Rani Karnavati, the widow of Rana Sanga, sent a rakhi to Humayun seeking his help, and Humayun gallantly responded. No contemporary writer has mentioned the story, and it may not be true. However, it is a fact that Humayun moved from Agra to Gwalior, and due to fear of Mughal intervention, Bahadur Shah patched up a treaty with the Rana, leaving the fort in his hands after extracting a large indemnity in cash and kind.

During the next year and a half, Humayun spent his time in building a new city at Delhi, which he named Dinpanah. He organised many grand feasts and festivities during the period. Humayun has been blamed for wasting valuable time in these activities, while Sher Khan was steadily augmenting his power in the east. It has also been said that Humayun's inactivity was due to his habit of taking opium. Neither of these charges is fully true. Babur had continued to use opium, after he gave up wine. Humayun took opium occasionally in place of or in addition to wine, as did many of his nobles. But neither Babur nor Humayun was an opium addict. The building of Dinpanah was meant to impress friends and foes alike. It could also serve as a second capital in case Agra was threatened by Bahadur Shah who, in the meantime, had conquered Ajmer and overrun eastern Rajasthan.

Bahadur Shah offered a still greater challenge to Humayun. He made his court the refuge of all those who feared or hated the Mughals. He had again invested Chittor and, simultaneously, supplied arms and men to Tatar Khan, a cousin of Ibrahim Lodi. Tatar Khan was to invade Agra, with a force of 40,000 while diversions were to be made in the north and the east.

Humayun easily defeated the challenge posed by Tatar Khan. The Afghan forces melted away at the approach of the Mughals, and Tatar Khan was defeated and killed. Determined to end the threat from Bahadur Shah's side once for all, Humayun nowinvaded Malwa. In the struggle which followed, Humayun showed considerable military skill, and remarkable personal valour. Bahadur Shah did not dare face the Mughals. He abandoned Chittor which he had captured, and his fortified camp, and fled to Mandu after spiking his guns, but leaving, behind all his rich equipage (trappings). Humayun was hot on his heels. He invested the fortress of Mandu and captured it without much opposition. Bahadur Shah fled from Mandu to Champaner. A small party scaled the fort of Champaner by a patch considered inaccessible.

Humayun was the forty first man to scale the walls. Bahadur Shah now fled to Ahmedabad and finally to Kathiawar. Thus, the rich provinces of Malwa and Gujarat, as well as the large treasure hoarded by the Gujarat rulers at Mandu and Champaner, fell into the hands of Humayun.

Both Gujarat and Malwa were lost as quickly as they had been gained. After the victory, Humayun placed Gujarat under the command of his younger brother, Askari, and then retired to Mandu which was centrally located and enjoyed a fine climate. The major problem was the deep attachment of the people to the Gujarati rule. Askari was inexperienced, and the Mughal nobles were mutually divided. A series of popular uprisings, military actions by Bahadur Shah's nobles, and the rapid revival of Bahadur Shah's power, unnerved Askari. He fell back upon Champaner, but received no help from the commander of the fort who doubted his intentions. Unwilling to face Humayun at Mandu, he decided to return to Agra. This immediately raised the fear that he might try to displace Humayun from Agra, or attempt to carve out a separate Empire for himself. Deciding to take no chances, Humayun abandoned Malwa and moved after Askari by forced marches. He overtook Askari soon. Finally, the two brothers reconciled with each other, and returned to Agra. Meanwhile, both Gujarat and Malwa were lost.

The Gujarat campaign was not a complete failure. While it did not add to the Mughal territories, it destroyed forever the threat posed to the Mughals by Bahadur Shah. Humayun was now in a position to concentrate all his resources in the struggle against Sher Khan and the Afghans. Soon after, Bahadur Shah was drowned in a scuffle with the Portuguese on board one of their ships. This ended whatever danger remained from the side of Gujarat.

5.0 Sher Khan

During Humayun's absence from Agra (February 1535 to February 1537), Sher Khan (an ethnic Pashtun) had further strengthened his position. He had made himself the unquestioned master of Bihar. The Afghans from far and near had rallied round him. Though he continued to profess loyalty to the Mughals, he systematically planned to expel the Mughals from India. He was in close touch with Bahadur Shah who had helped him with heavy subsidies. These resources enabled him to recruit and maintain a large and efficient army which included 1200 elephants. Shortly after Humayun's return to Agra, he had used this army to defeat the Bengal king, and compel him to pay an indemnity of 13,00,000 dinars (gold coins).

After equipping a new army, Humayun marched against Sher Khan and besieged Chunar towards the end of the year. Humayun felt it would be dangerous to leave such a powerful fort behind, threatening his line of communications. However, the fort was strongly defended by the Afghans. Despite the best efforts by the mastergunner, Rumi Khan, it took six momhs for Humayun to capture it. In the meanwhile, Sher Khan captured by treachery the powerful fort of Rohtas where he could leave his family in safety. He then invaded Bengal for a second time, and, captured Gaur, its capital.

Thus, Sher Khan completely outmanoeuvred Humayun. Humayun should have realised that he was in no position to offer a military challenge to Sher Khan without more careful preparations. However, he was unable to grasp the political and military situation facing him. After his victory over Gaur, Sher Khan made an offer to Humayun that he would surrender Bihar and pay an annual tribute of ten lac dinars if he was allowed to retain Bengal. It is not clear how far Sher Khan was sincere in making this offer. But Humayun was not prepared to leave Bengal to Sher Khan. Bengal was the land of gold, rich in manufactures, and a centre for foreign trade. Moreover, the king of Bengal who had reached Humayun's camp in a wounded condition, urged that resistance to Sher Khan was still continuing. All these factors led Humayun to reject Sher Khan's offer and decide upon a campaign to Bengal. Soon after, the Bengal king succumbed to his wounds. Humayun had, thus, to undertake the campaign to Bengal all alone.

Humayun's march to Bengal was purposeless, and was the prelude to the disaster which overtook his army at Chausa almost a year later. Sher Khah had left Bengal and was in south Bihar. He let Humayun advance into Bengal without opposition so that, he might disrupt Humayun's communications and bottle him up in Bengal. Arriving at Gaur, Humayun quickly took steps to establish law and order. But this did not solve any of his problems. His situation was made worse by the attempt of his younger brother, Hindal, to assume the Crown himself at Agra. Due to this and Sher Khan's activities, Humayun was totally cut off from all news, and supplies from Agra.

After a stay of three to four months at Gaur, Humayun started back for Agra, leaving a small garrison behind. Despite the rumblings of discontent in the nobility, the rainy season, and the constant harrying attacks of the Afghans, Humayun managed to get his army back to Chausa near Buxar, without any serious loss. This was a big achievement for which Humayun deserves credit. Meanwhile, Kamran had advanced from Lahore to quell Hindal's rebellion at Agra.Though not disloyal, Kamran made no attempt to send reinforcements to Humayun which might have swung the military balance in favour of the Mughals.

Despite these setbacks, Humayun was still confident of success against Sher Khan. He forgot that he was facing an Afghan army which was very different from the one a year before. It had gained battle experience and confidence under the leadership of the most skilful general the Afghans ever produced. Misled by an offer of peace from Sher Khan, Humayun crossed over to the eastern bank of the Karmnasa river, giving full scope to the Afghan horsemen encamped there to attack. Humayun showed not only bad political sense, but bad generalship as well. He chose his ground badly, and allowed himself to be taken unawares.

Humayun barely escaped with his life from the battle field, swimming across the river with the help of a water-carrier. Immense booty fell in Sher Khan's hands. About 7000 Mughal soldiers and many prominent nobles were killed.

5.1 The Battle of Kannauj

After the defeat at Chausa (March 1539), only the fullest unity among the Timurid princes and the nobles could have saved the Mughals. Kamran had a battle-hardened force of 10,000 Mughals under his command at Agra. But he was not prepared to loan them to Humayun as be had lost confidence in Humayun's generalship. On the other hand, Humayun was not prepared to entrust the command of the armies to Kamran, lest the latter use it to assume power himself. The suspicions between the brothers grew till Kamran decided to return to Lahore with the bulk of his army.

The army hastily assembled by Humayun at Agra was no match against Sher Khan. However, the battle of Kannauj (May 1540) was bitterly contested.

The battle of Kannauj decided the issue between Sher Khan and the Mughals. Humayun, now, became a prince without a Kingdom, Kabul and Qandhar remaining under Kamran. He wandered about in Sindh and its neighbouring regions for the next two and a half years, hatching various schemes to regain his kingdom. But neither the rulers of Sindh nor Maldeo, the powerful ruler of Marwar, was prepared to help him in this enterprise. Worse, his own brothers turned against him, and tried to have him killed or imprisoned. Humayun faced all these trials and tribulation with fortitude and courage. It was during this period that Humayun's character showed itself at its best. Ultimately, Humayun took shelter at the court of the Iranian king and recaptured Qandhar and Kabul with his help in 1545.

It is clear that the major cause of Humayun's failure against Sher Khan was his inability to understand the nature of the Afghan power. Due to the existence of large numbers of Afghan tribes scattered over north India, the Afghans could always reunite under a capable leader and pose a challenge. Without winning over the local rulers and zamindars to their side, the Mughals were bound to remain numerically inferior. In the beginning, Humayun was, on the whole, loyally served by his brothers. Real differences among them arose only after Sher Khan's victories. Some historians have unduly exaggerated the early differences of Humayun with his brothers, and his alleged faults of character. Though not as vigorous as Babur, Humayun showed himself to be a competent general and politician, till his ill-conceived Bengal campaign.

In 1555, following the breakup of the Sur Empire, he was able to recover Delhi. But he did not live long to relish the victory. He died from a fall from the first floor of the library building in his fort at Delhi. His favourite wife built a magnificent mausoleum for him near the fort. This building marks a new phase in the style of architecture in north India, its most remarkable feature being the magnificent dome of marble.

6.0 Sher Shah and the Sur Empire (1540-55)

Sher Shah (or Sher Shah Suri / Sher Khan) ascended the throne of Delhi at the ripe age of 67. We do not know much about his early life. His original name was Farid and his father was a small jagirdar at Jaunpur. Farid acquired rich administrative experience by looking after the affairs of his father's jagir. Following the defeat and death of Ibrahim Lodi and the confusion in Afghan affairs, he emerged as one of the most important Afghan sardars. The title of Sher Khan was given to him by his patron for killing a tiger (sher). Soon, Sher Khan emerged as the right-hand of the ruler of Bihar, and its master in all but name. This was before the death of Babur. The rise of Sher Khan to prominence was, thus, not sudden.

As a ruler, Sher Shah ruled the mightiest Empire which had come into existence in north India since the time of Muhammad bin Tughlaq. His Empire extended from Bengal to the Indus, excluding Kashmir. In the west, he conquered Malwa, and almost the entire Rajasthan. Malwa was then in a weak and distracted condition and in no position to offer any resistance. But the situation in Rajasthan was different.

Maldeo Rathore, the ruler of Marwar, who had ascended the gaddi in 1532, had rapidly brought the whole of western and northern Rajasthan under his control. He further expanded his territories during Humayun's conflict with Sher Shah. With the help of the Boatis of Jaisalmer, he conquered Ajmer. In his career of conquest he came into conflict with the rulers of the area, including Mewar. His latest act had been the conquest of Bikaner. In the course of the conflict, the Bikaner ruler was killed after a gallant resistance. His sons, Kalyan Das and Bhim, sought shelter at the court of Sher Shah.

Thus, the situation facing Rana Sanga and Babur was repeated. Maldeo's attempt to create a large centralised state in Rajasthan under his aegis was bound to be regarded as a threat by the ruler of Delhi and Agra. It was believed that Maldeo had an army of 50,000. However, there is no evidence that Maldeo coveted Delhi or Agra, Now, as before, the bone of contention between the two was the domination of the strategically important eastern Rajasthan.

6.1 The Battle of Samel

The Rajput and Afghan forces clashed at Samel (1544) between Ajmer and Jodhpur. After waiting for about a month, Maldeo suddenly withdrew towards Jodhpur. According to contemporary writers, this was due to a clever stratagem on the part of Sher Shah. He had dropped some letters addressed to the Rajput commanders near Maldeo's camp, in order to sow doubt in his mind about their loyalty. Soon, superior number and Afghan gunfire halted the Rajput charge, and led to their defeat.

The battle of Samel sealed the fate of Rajasthan, Sher Shah now besieged and conquered Ajmer and Jodhpur, forcing Maldeo into the desert. He then turned towards Mewar. The Rana was in no position to resist, and sent the keys of Chittor to Sher Shah who set up his outposts up to Mount Abu.

Thus, in a brief period of ten months, Sher Shah overran almost the entire Rajasthan. His last campaign was against Kalinjar, a strong fort that was the key to Bundelkhand. During the siege, a gun burst and severely injured Sher Shah. He died (1545) after he heard that the fort had been captured.

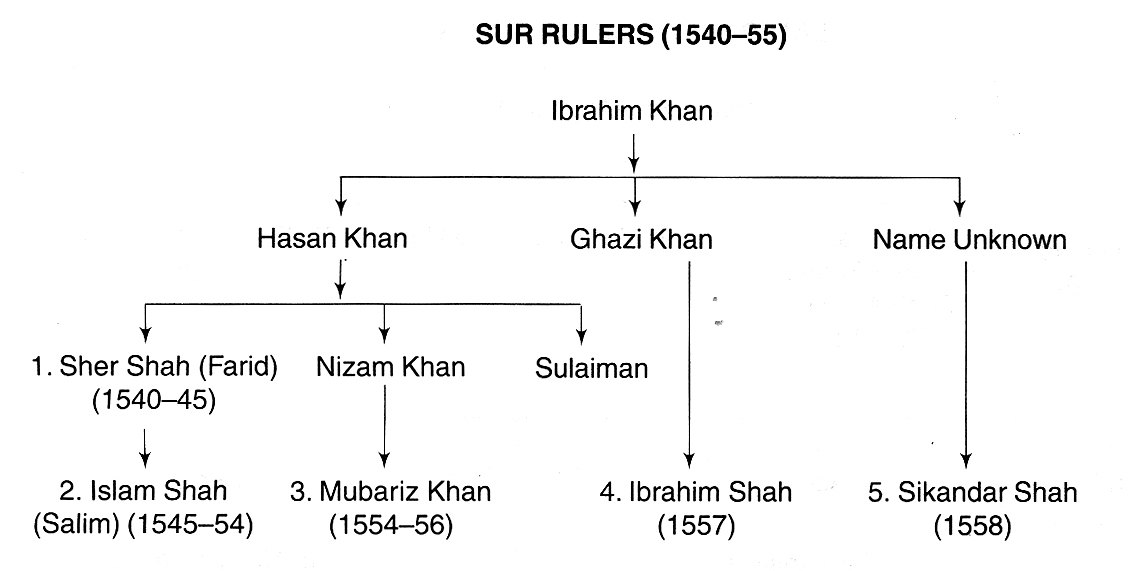

6.2 Islam Shah

Sher Shah was succeeded by his second son, Islam Shah, who ruled till 1553. Islam Shah was a capable ruler and general, but most of his energies were occupied with the rebellions raised by his brothers, and with tribal feuds among the Afghans. These and the ever present fear of a renewed Mughal invasion prevented Islam Shah from attempting to expand his Empire. His death at a young age led to a civil war among his successors. This provided Humayun the opportunity he had been seeking for recovering his Empire in India. In two hotly contested battles in 1555, he defeated the Afghans, and recovered Delhi and Agra.

6.3 Contribution of Sher Shah

The Sur Empire may be considered in many ways as a continuation and culmination of the Delhi sultanate, the advent of Babur and Humayun being in the nature of an interregnum. Amongst the foremost contributions of Sher Shah was the re-establishment of law and order across the length and breadth of his Empire. He dealt sternly with robbers and dacoits, and with zamindars who refused to pay land revenue or disobeycd the orders of the government. We are told by Abbas Khan Sarwani, the historian of Sher Shah, that the zamindars were so cowed that none of them dared to raise the banner of rebellion against him, or to molest the travellers passing through their territories.

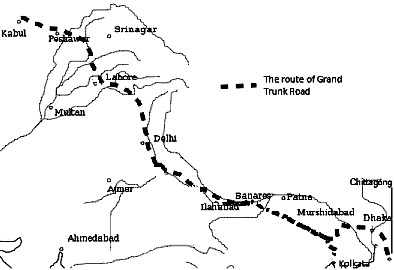

Sher Shah paid great attention to the fostering of trade and commerce, and the improvement of communications in his ingdom. Sher Shah restored the old imperial road called the Grand Trunk Road, from the river Indus in the west to Sonargaon in Bengal. He also built a road from Agra to Jodhpur and Chittor, evidently linking up with the road to the Gujarat seaports. He built a third road from Lahore to Multan. Multan was at that time the staging point for caravans going to West and Central Asia. For the convenience of travellers, Sher Shah built a sarai at a distance of every two kos (about eight km) on these roads. The sarai was a fortified lodging or inn where travellers could pass the night and also keep their goods in safe custody. Separate lodgings for Hindus and Muslims were provided in these sarais. Brahmanas were appointed for providing bed and food to the Hindu travellers, and grain for their horses. Abbas Khan says, "It was a rule in these sarais that whoever entered them received provision suitable to his rank, and food and litter for his cattle, from government." Efforts were made to settle villages around the sarais, and land was set apart in these villages for the expenses of the sarais. Every sarai had several watchmen under the control of a shahna (custodian).

Sher Shah also introduced other reforms to promote the growth of trade and commerce. In his entire Empire, goods paid customs duty only at two places: goods produced in Bengal or imported from outside paid customs duty at the border of Bengal and Bihar at Sikrigali, and goods coming from West and Central Asia paid customs duty at the Indus. No one was allowed to levy customs at roads, ferries or towns anywhere else. The duty was paid a second time at the time of sale.

Sher Shah directed his governors and amils to compel the people to treat merchants and travellers well in every way, and not to harm them at all. If a merchant died, they were not to seize his goods as if they were unowned. Sher Shah enjoined upon them the dictum of Shaikh Nizami: "If a merchant should die in your country it is a perfidy to lay hands on his property." Sher Shah made the local village headmen (muqaddams) and zamindars responsible for any loss that the merchant suffered on the roads. If the goods were stolen, the muqaddams and the zamindars had to produce them, or to point out the haunts of the thieves or highway robbers, failing which they had to undergo the punishment meant for thieves and robbers. The same law was applied in cases of murders on the roads. It was a barbarous law to make the innocent responsible for the wicked but it seems to have been effective. In the picturesque language of Abbas Sarwani, "a decrepit old woman might place a basketful of gold ornaments on her head and go on a journey, and no thief or robber would come near her for fear of the punishment which Sher Shah inflicted."

The currency reforms of Sher Shah also helped in the growth of commerce and handicrafts. He struck fine coins of gold, silver and copper of uniform standard in place of the debased coins of mixed metal. His silver rupee was so well executed that it remained a standard coin for centuries after him. His attempt to fix standard weights and measures all over the Empire were also helpful for trade and commerce.

Sher Shah, apparently continued the central machinery of administration which had been developed during the Sultanate period. However, not much information about it is available. Sher Shah did not favour leaving too much authority in the hands of ministers. He worked exceedingly hard, devoting himself to the affairs of the state from early morning to late at night. He also toured the country constantly to know the condition of the people. But no single individual, however hardworking, could look after all the affairs of a vast country like India. Sher Shah's excessive centralisation of authority in his hands was a source of weakness, and its harmful effects became apparent when a masterful sovereign like him ceased to sit on the throne.

Sher Shah paid special attention to the land revenue system, the army and justice. Having administered his father's jagir for a number of years, and then as the virtual ruler of Bihar, Sher Shah knew the working of the land revenue system at all levels. With the help of a capable team of administrators, he toned up the entire system. The produce of land was no longer to be based on guess work, or by dividing the crops in the fields or on the threshing floor. Sher Shah insisted on measurement of the sown land. Schedule of rates (called ray) was drawn up, laying down the state's share of the different types of crops. This could then be converted into cash on the basis of the prevailing market rates in different areas. The share of the state was one-third of the produce. The lands were divided into good, bad and middling. Their average produce was computed, and one-third of it became the share of the state. The peasants were given the option of paying in cash or kind, though the state preferred cash.

A big step forward in the dispensation of justice was, however, taken by Sher Shah's son and successor, Islam Shah, who codified the laws, thus doing away with the necessity of depending on a special set of people who could interpret the Islamic law. Islam Shah also tried to curb the powers and privileges of the nobles, and to pay cash salaries to soldiers. But most of the regulations disappeared with his death.

There is no doubt that Sher Shah was a remarkable figure. He established a sound system of administration in his brief reign of five years. He was also a great builder. The tomb which he built for himself at Sasaram during his lifetime is regarded as one of the masterpieces of architecture. It is considered as a culmination of the earlier style of architecture and a starting point for the new style which developed later.

Thus, the state under the Surs remained an Afghan institution based on race and tribe. A fundamental change came about only with the emergence of Akbar.