Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - being learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

Evolution of religion

1.0 Introduction

Brahmanism acquired its characteristic form soon after the period of the Upanishads (about 800 to 400 BC). Theoretically the Vedic religion forms its basis, but in fact it is only one of the main factors in the long and ever evolving cultural synthesis.

The Hindu religion of which Brahmanism is a part, is an aggregation of innumerable religious beliefs, of cults, of customs and of rituals. It cannot be treated as a single religion, since it has no founder, no single sacred order to institute set dogmas, and no central organisation.

From the mutual interactions of the Deccan Neolithic (dating from about 2000 to 750 bc), the Dravidians, which contributed greatly to the development of the later devotional cults, the tribal & native groups which constitute the lowest stratum of society, and the Aryan culture arose a vast, uncoordinated mass of new and continually changing religious beliefs and practices, some being developed, others modified, and others almost disappearing.

Anything that has even a vestige of religious significance is never discarded and may come again to the fore centuries later. Thus no single religious system can be said to represent Brahmanism in its entirety.

2.0 Origin of Brahmanism

The earliest use of the term Brahman referred to the holy sacred power assumed to be in a vedic chant which would make the message reach God. Later, the priest officiating the sacrifice came to be known as Brahman. The term can also be used as a noun to refer to the sacred power which is the source and the sustainer of the whole universe.

The worship of yakshas and nagas, and other folk-deities constituted the most important part of primitive religious beliefs. Both literary and archaeological evidence prove the existence of this form of worship among the people. Several free-standing images of the yaksas, yaksinis, nagas and naginis belonging to the centuries before and after the Christian era are found in several parts of the country. The folk-cults centred on the yaksas and nagas survived in the orthodox Brahmanical fold in the form of worship of Ganesha (the elephant headed deity), whose hybrid figure was an amalgam of the pot-bellied yaksa and the elephantine naga (the word naga meant both 'snake' and an 'elephant'). The original importance of the folk element in religion is also apparent in the fact that the first place was assigned to Ganesha in the list of the five principal Puranic deities (Ganeshadi Panchadevata- Ganesha, Vishnu, Shiva, Shakti and Surya).

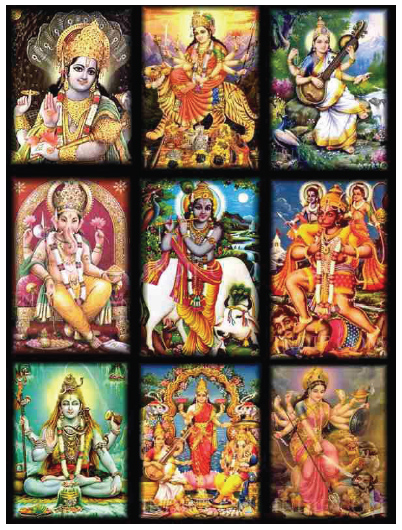

3.0 GODS IN HINDUISM

Contrary to prevailing misconceptions, all Hindus worship a one Supreme Being, though by different names. This is because the peoples of India with different languages and cultures have understood the one God in their own distinct way(s). Through history, there arose four principal Hindu denominations - Shaivism, Shaktism, Vaishnavism and Smartism. For Shai-vites, God is Siva. For Shaktas, Goddess Shakti is supreme. For Vaishnavites, Lord Vishnu is God. For Smartas - who see all Deities as reflections of the One God - the choice of Deity is left to the devotee. This liberal Smarta perspective is well known, but it is not the prevailing Hindu view. Due to this diversity, Hindus are profoundly tolerant of other religions, respecting the fact that each has its own pathway to the one God.

One of the unique understandings in Hinduism is that God is not far away, living in a remote heaven, but is inside each and every soul, in the heart and consciousness, waiting to be discovered. This knowing that God is always with us gives us hope and courage. Knowing the One Great God in this intimate and experiential way is the goal of Hindu spirituality.

3.1 Gods

The Sanskrit term for god is deva, derived from the root word div which mean 'to shine' or 'to be radiant'. It is applied to any abstract or cosmic potency which may be manifested as human beings, or as animals with divine status, or as incarnations (avataras).

Most of the Vedic deities are deifications of the powers of nature, with natural disasters and diseases being attributed to malevolent powers such as Vrtra, or the goddess Ninti, the personification of decay, destruction and death. By the first century AD, most Hindus were either Vaishnavas or Shaivas. They lived together amicably, with no feeling of exclusiveness among the members of these cults. Such mutual tolerance led naturally to syncretistic divine forms such as the triad (Trimurti) promulgated in Gupta times. It consists of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. Vishnu incarnates himself to save mankind. Shiva is the third member of the triad. His special function is to preside over the dissolution of the world; but he too can intervene to save it when it is endangered. A more popular syncretism than the triad was that of Harihara {Hari is a name for Vishnu, and Hara is a name of Siva - and in the south it became Ayyappa - Ayya for Vishnu, Appa for Shiva}.

The great diversity of man's spiritual conception is explained by the Samkhya teaching of the three gunas, the main constituents comprising everything in the world. Thus, in the highest conception of divinity as the embodiment of goodness, beneficence, perfection and radiance, the sattva guna predominates; when god is regarded as wrathful, cruel and violent, the rajas guna is uppermost; and when a god of disease, pestilence, destruction and death is envisaged the tamas guna is to the fore.

3.2 The Goddess (Devi)

Rig Vedic goddesses, their attributes and what they smybolise, are given as follows:

- Ida represents the sacrificial food or libations,

- Hotra and Svaha are personifications of the ritual invocations,

- Although the Rig Veda implies that the goddesses are subordinate to the gods, Aditi nonetheless stands out from the rest. She represents freedom and infinity that contains everything else including the gods. Her twelve sons, collectively called the Adityas, represent the months of the solar years and are invoked to bestow benefits on mankind,

- Another goddess to whom about twenty five hymns are addressed is Ushas, the rosy goddess of the dawn, who signifies the victory of light over darkness and that of life over death.

Other Vedic goddesses include

- Prithvi, the personification of Earth

- Diti, the mother of the Daityas

- Aranyani, the elusive goddess of forests and wild creatures

- Vac (Speech)

- Puramdhi and Dhisana, both representing abundance

- Raka and Sinivali, beneficent goddesses, lla, the 'mother of the cattle herds'; and

- Ninti, goddess of misfortune, decay and death.

In the Shakta and Tantric cults the goddess, as Shakti, represents the visible universe arising from the universal Brahman. In other words, the ultimate principle of the universe is regarded as female. Shakti is the overflowing cosmic energy through which gods, world and all creatures come into being. In fact, she is indistinguishable from nature i.e. prakriti.

In post-Vedic times, Shakti is conceived as the power (shakti) of the gods and is associated with them in the form of their consorts. Literary references to her become more frequent from the 7th century onwards when she became Shiva's consort. Her gentle forms are called Parvati, Uma, Padma and Gauri; and her fierce forms are Shyama, Bhairavi, Chamunda, Kali and Durga.

The skull-garlanded goddess Kali is especially popular in Bengal, where her cult has somewhat overshadowed many of the local deities such as Manasa (the goddess of snakes), Shitala (goddess of smallpox), Chandi (goddess of hunters), and others. Kali also includes among her many manifestations the ten mahavidyas, the Seven Mothers, the sixty four Yoginis, and the dakinis.

Today the most popular goddess is Shri, the personification of prosperity and beauty. She is mentioned once in the Rig Veda and more frequently in the Atharva Veda and other works. Later she became linked with the post-Vedic goddess Lakshmi, who emerged from the 'Ocean of Milk' when the devas and asuras churned it. The association of the two goddesses and the varied myths associated with them suggests the assimilation of numerous folk traditions. Shri is said to dwell in garlands and hence prosperity, good fortune and victory are ensured for those who wear them.

3.3 Spirits, Sprites and Godlings

Alongside the Vedic cult and the Vaishnava, Shaiva and Sakta cults, countless forms of animism and nature worship exist in India. Most of these local spirits stem from the aboriginal past and many have been absorbed gradually by the higher cults.

Yakshas, the mysterious beings (also common to Buddhism and Jainism) are apparitions or manifestations of the numinous. They frequent lonely places and were probably the vegetal godlings of pre-Aryan communities. Yakshas are often honoured by a stone tablet or altar placed under a sacred village tree, their presence ensuring the prosperity of the village.

Their feminine counterparts, the yakshinis, symbolise the life sap of vegetation. Some yakshas cause insanity and other diseases. Like other supernatural beings, yakshas may be benevolent or malevolent towards man. As protectors of the community they are often depicted on local shrines and doorposts as virile and powerful men. In later mythology the leader of the yakshas is Kubera, god of wealth.

Included among the multitude of spirits are the pretas, ethereal forms of the newly dead. Spirits of the long dead people become ancestors or fathers (pitrus), yet both pretas and pitrus remain active in the world and occasionally assist their descendants. The deceased cannot be united with his ancestors and raised to the status of a pitru until the correct funeral rites (shraddhas) have been performed, rites which include the offering of water and funerary cakes (pindas) to the three immediate generations of the deceased's forebears.

The souls of those who die violent deaths become malevolent bhutas (night-wandering ghosts) who are assimilated to particular pretas, especially those who have died unnatural deaths or whose funerary rites have not been performed. Such bhutas haunt trees and derelict buildings and are worshipped by some people in northern India.

Pretas, and other demonic spirits, called pishachas, also appear dancing among the dead and wounded on battlefields, or in burial grounds. They personify the forces of darkness, cruelty, violence and death as do the yatudhanas, guardians of Kubera's mountain. The yatudhanas are associated with aboriginal tribes and are said to have animal hoofs.

Other beings belonging to the sphere between man and gods are the gandharvas, celestial musicians and inspirers of earthly musicians, singers and dancers. Their female counterparts, the nymph-like apsarasas, the dancers of the gods, may cause war in men. Both gandharvas and apsarasas dwell in specific trees.

The yoginis (the female form of yogi) are regarded as witches or demonesses, which reflects the misogynist attitude prevalent in the larger part of Indian tradition, and also explains the ban on women attempting to practise yoga. The yoginis are attendant on Durga and Shiva, and are sometimes regarded as minor epiphanies of Durga. Other demonesses associated with Durga are the sakinis and dakinis, eaters of raw flesh. The dakinis are connected with both Buddhist and Hindu Tantrism.

4.0 SECTS OF BRAHMANISM

Along with the appearance of religions of non-theistic nature (heterodox sects were non-theistic at least in the beginning in the sense that they were more or less of an ethical character and did not encourage vague enquiries about god and soul), creeds of a definitely theistic character came to be evolved. The central figures around which they grew up were not primarily Vedic deities but come from unorthodox sources. In fact, pre-Vedic and post-Vedic folk elements were most conspicuous in their origin. The important factor that activated these theistic movements was bhakti (the single-souled devotion of the worshipper to a particular god). This stimulus led to the evolution of different religious sects like Vishnavism, Shaivism and Shaktism, all of which came to be regarded as components of orthodox Brahmanism.

4.1 Vaishnavism

The rise and growth of Vaishnavism was closely connected with that of Bhagavatism. Vaishnavism, having its origins in the pre-Gupta period, began to capture and absorb Bhagavatism during the Gupta period. This process of capture and absorption was completed by the end of the late Gupta period, and in fact the name mostly used to designate Bhagavatism from this period onwards was Vaishnavism, indicating the predominance of the later Vedic Vishnu element in it with emphasis on the doctrine of incarnations.

Vishnu is a conflation of many local divinities. These include a Vedic god having some solar char acteristics; a popular deified hero, Vasudeva, worshipped in western India; and the philosophical 'Absolute' of the Upanishads.

This assimilation of deities occurred before the second century Bc, since an inscription on a pillar at Besnagar states that the Greek ambassador Hetiodorous was a devotee of the 'God of gods' Vasudeva. Vasudeva is said to have propounded the Bhagavata religion which included some solar features and later developed into Vaishnavism.

The theory of incaranation greatly facilitated the assimilation of popular divinities into Vaishnavism. It developed during the Epic period and is referred to in the Puranas.

The stages by which Vishnu rose to become a major deity are lost in the distant past, but some clues remain; the Rig Veda identifies Bhaga, the lord of bounty, with Varuna and later with Vishnu; and the Brahmanas identify Vishnu with the personified sacrifice and with the 'Cosmic Man' whose sacrificial dismemberment gave rise to the universe.

4.1.1 Vaishnava cults

Bhagavatas: The Bhagavata and Pancharatra initially cults were separate, the Pancharatras worshipping the deified sage Narayana, and the Bhagavatas worshipping the deified Vrisni hero Vasudeva. The two sects were later amalgamated in an attempt to identify Narayana and Vasudeva.

The Bhagavata is a theistic devotional cult which originated several centuries before the Christian era. It is based mainly on the Bhagavad Gita, but later Bhagavata Parana and Vishnu Purana became its main texts.

When the Bhagavata cult reached its peak during the second century AD, it came to be generally known as the Pancharatra Agama. The name means 'five nights', but its significance is unknown.

The adherence of the Rajput kings to Bhagavatism further spread to the whole of India. In southern India, in the Tamil land, the Bhagavata movement was spread largely by the twelve Alvars (who had intuitive knowledge of God). They flourished from the eighth to the early nineth century.

The Alvars belonged to various classes of society. Among them were a king of Malabar, a famous woman, Andal, to whom a magnificent temple was later built at her birthplace, Srivilliputtur; by a low caste man; and a repentant sinner. After the Alvars came the Acharyas who united devotion with knowledge and karma.

Panchatantra: According to tradition the Panchatantra teachings were first systematised in about 100 AD by Sandilya, who stressed the need for total devotion to Vasudeva Krishna.

A cosmoiogical basis was given to Vasudeva Krishna by identifying him and the members of his family with specific cosmic emanations (Vyuhas): this was an important tenet of the early Pancharatras and of the later Sri Vaishnava cult. The 'emanatory theory' developed early in the Christian era, about the same time as the theory of incarnation.

The Pancharatras postulate a supreme Brahman, who reveals himself as Vishnu, Vasudeva and Narayana and whose power gives birth to the universe. At the beginning of Time, the supreme aspect of Vasudeva created from himself the vyuha Samkarshana (a name of Krishna's brother) identified with primal matter (prakriti). From these two combines, Krishna's son Pradyumna was produced and identified with mind (manas). From these arose Aniruddha (Krishna's grandson) identified with self-consciousness (ahankara). From the last two sprang the five elements (panchabhutas) and their qualities (mahabhutas) simultaneously with Brahma who fashioned the earth and everything in it from these elements.

The last three emanations are regarded not only as aspects of the divine character, but as gods in their own right. Thus paradoxically the gods are both one and many. Later their worship declined when the concept of Vishnu's incarnations became popular and dominated Vaishnavism during the Gupta Age. All the above deified heroes were worshipped in the Mathura region by people of Yadava-Satvata Vrisni origin (Krishna was a Yadava), and the teaching was carried to western India and northern Deccan by migrating Yadava tribes.

Vaikhanasas: This ritualistic cult was founded by the legendary Vikhanas whose teaching was disseminated by four ancient sages: Atri, Marichi, Bhrigu and Kashyapa.

Initially the cult formed part of the Taittiriya school of the Black Yajur Veda, but later it became an orthodox Vaishnava cult. In its main text, the Vaikhanasa Sutra (dated about the 3rd century AD), the cult of the Vedic solar Vishnu coalesces with that of Narayana.

Vaikhanasa ritual theory is based on the five-fold conception of Vishnuas brahman (the supreme deity); as purusha, as satya, as achyuta (the immutable) and as aniruddha (the irreducible aspect). Performing the five-fold ritual expiates evil and bestows happiness on everyone.

Vishnu's dashavataras are also worshipped for specific purposes. Image worship is important in this movement and is said to be a development of symbolic Vedic ritual.

From the end of the tenth century Vaikhanasa priests were in charge of Vaishnava temples and shrines. Although somewhat eclipsed by the rise of the Sri Vaishnava cult, the priests still perform rituals in the Sanskrit language at some temples, including the Venkatesvara temples at Tirupati and Kanchi.

Alvars or Vaishnava Saints: The history of Vaishnavism from the post-Gupta period till the first decade of the 13th century AD is concerned mostly with south India. Vaishnava saints, popularly known as Alvars in south India, preached one-souled, loving adoration for Vishnu, and their songs in Tamil were collectively named Prabhandhas. Among the 12 Alvars, the most famous are Nammalvar and Tirumalisai Alvar.

Vaishnava Acharyas or Teachers: The wave of Vishnubhakti of the Alvars was supplemented on its doctrinal side by a class of Vaishnava teachers, popularly known as the Vaishnava Acharyas in south India. Ramanuja, one of the early great Acharyas, along with Yamunacharya (another important early Acharya) developed the doctrine of Visishtadvaita (qualified non-dualism) on the basis of some Upanishadic texts in opposition to Sankaracharya's Advaitavada or non-dualism (Sankara does not belong to either Vaishnavism or Saivism but to the nirguna school). Two other Vaishnava Acharyas of south India, who lived after Ramanuja, were Madhvacharya and Nimbarka. The former founded the Dvaitavada (dualism) and the latter Dvaitadvaitavada (dualistic non-dualism) in Vaishnavism.

Thus, while the Alvars represented the emotiona] side of south Indian Vaishnavism, the Acharyas

represented its intellectual aspect.

4.2 Shaivism

Origin and growth: Shaivism, unlike Vaishnavism, had its origin in the very ancient past. The pre-Vedic religion (i.e. Indus religion) has, as one of its important components the worship of Pashupati Mahadeva, a deity conveniently described as proto-Shiva. In the Vedic religion, particularly the later Vedic religion, Rudra can be considered as the Vedic counterpart of Pashupati Mahadeva.

However, it is the grammarians of the post-Vedic period who give us an idea about the growth of Shaivism as a religious movement. Panini, for instance, refers to a group of Shiva worshippers of his time. Patanjali also describes a group of Shiva-worshippers named by him as Siva Bhagavatas in his Mahabhasya (second century BC). Patanjali refers indirectly and briefly to the forceful and outlandish ritualism of these worshippers of Shiva. This reminds us of the extreme religious practices of the Pashupatas described in the Pashupata Sutras.

Shaivism, thus, came to the fore in post-Upanishadic times, when Shiva is identified with the terrifying Vedic god Rudra. The word Shiva means 'auspicious'. Shiva's many names, attributes and epithets indicate his diverse functions.

- As the personification of the disintegrating power of time, he is called 'Kala' and depicted adorned with garlands of human skulls, and has his body entwined with snakes symbolising the cycle of time.

- As the passing of time inevitably leads to death, he is called 'Mahakala' or 'Hara', the remover. Consequently he is said to dance in cremation grounds and on battle fields.

- As the Lord of Mountains, he is 'Girisha'.

- As the Lord of Animals and Hunters, he is 'Pasupati' who represents the destruction of life by hunting, war and disease.

- As Lord of Demons (bhutas), he is 'Bhutanatha'.

- As the supreme yogin, he is 'Mahayogi’.

- As guru of yogic knowledge, music and the Veda, he is 'Dakshinamurthi'.

- As the giver of the bliss arising from absolute knowledge, he is 'Shankara'.

- As the cosmic Lord of Dance ('Nataraja'), he embodies the universal energy.

Shiva is universally worshipped in the form of the phallus (linga), the source of manifestation and life, which inevitably contains the seeds of disintegration and death. The female generative organ (yoni) represents Shiva's shakti, the personification of his cosmic energy. When represented together, the linga and the yoni signify the two great generative principles of the universe.

Some of the Puranas identify the whole of creation with Shiva through the doctrine of his five faces - Ishana, Tatpurusha, Aghora, Vamadeva and Sadyojata. Shiva's five faces are personified as the rulers of the five directions, the four points of the compass and the zenith, making up the totality of spatial extension.

Shaivism flourished under the Gupta dynasty although most of them were Vaishnavas. In south India, the Pallava king Mahendravarman I was at first a Jaina and later a Shaiva. Royal patronage greatly increased the popularity of Shaivism, as did the mystical and devotional poems composed by the sixty-three Shaiva Nayanars (also called Adiyars).

Nayanars or Shaiva Saints: Shaivism in south India, like Vaishnavism, flourished in the beginning through the activities of Shaiva saints, popularly called the Nayanars. Their poetry in Tamil was called Tevaram (also known as Dravida Veda). There are 63 Nayanars, the most important among them being Tirujnana Sambandhar and Tirunavukkarasu (popularly known as 'Appar').

Shaiva Acharyas or Teachers: The emotional Shaivism preached by the Nayanars was supplemented on the doctrinal side by a large number of Shaiva intellectuals (Acharyas) who were associated with several forms of Shaiva movements like Agamanta, Shuddha and Virasaiva. The Agamantas based their tenets mainly on the 28 agamas which explain the various aspects of Shiva. Aghora Shivacharya was one of their best exponents. The Shuddhashaivas upheld Ramanuja's teachings and Srikanta Shivacharya was their great expounder. The Virasaivas or Lingayats were led by Basava (a minister of Chalukya king Bijjala Raya of the 12th century AD). Basava used his political power and position in furthering the cause of this movement which was both a social and religious reform movement. These people were also influenced by Ramanuja's teachings.

Shaiva Cults: The Pashupata doctrine, founded by Lakulehsa, was dualistic in nature. Pashu (the individual soul) was eternally existing with the pati (the supreme soul), and the attainment of dukkhania (end of misery) was through the performance of yoga and vidhi (means). This vidhi consisted of various senseless and unsocial acts (or extreme acts). The Kapalikas and the Kalamukhas were undoubtedly off-shoots of the Pashupata sect and there is enough epigraphic evidence to show that these were already flourishing in the Gupta period. Other extreme sects of Saivism are the Aghoris (successors of Kapalikas) and the Gorakhnathis.

In contrast to the above mentioned extreme forms, some moderate forms of Shaivism also appeared in northern and central India in the early medieval period. In Kashmir two moderate schools of Shaivism were founded. Vasugupta founded the Pratyabhijna school, and his pupils, Kaflata and Somananda, founded the Spandasastra school. Allthese teachings were systematised by Abhinava Gupta who founded a new monistic system, called the Trika. Another moderate Shaiva sect, known as Mattamayuras, flourished at the same time in central India and a little later in some parts of the Deccan. Epigraphic evidence from central India shows that many of the Mattamayura Acharyas were preceptors of the Kalachuri-Chedi kings.

Pashupatas: This is probably the earliest known Shaiva cult as suggested by the name and Shiva's title of Lord of Animals (pashu 'animal' and pati 'lord'). The cult flourished in Orissa and in western India from the 7th to the 11th centuries.

The founder of the Pashupata cult was Lakulesha (or Lakulish), said to be an incarnation of Shiva. Lakulesha’s special emblem was a club (lakuta) which sometimes symbolises the phallus. He is usually depicted naked and ithyphallic. The latter state does not signify sexual excitement but sexual restraint by means of yogic techniques.

The cult's main text is the Pashupata Sutra attributed to Lakulesha. It is primarily concerned with ritual and discipline. According to a 13th century inscription Lakulesha had four chief disciples who founded four subsects. A number of Pashupata temples were established in northern India from about the 6th century onwards, but by the 11 th century the movement was in decline.

The ultimate aim of the cult is to attain eternal union with Shiva and thereby overcome all pain and suffering. There are various stages to this goal. In the first stage a follower serves in a temple and wears only one garment, or will be naked. Later he leaves the temple, removes the sectarian marks, and behaves in an idiotic or indecent way, thereby inviting the ridicule and disgust of orthodox Hindus. The ridicule of others counteracts the devotee's own bad Karmic effects and transfers to him the merit of those who have sworn at him. The indecent behaviour is a means of cutting off the devotee from ordinary society and producing in him a state of tranquil detachment and hence he should live in a cave, a derelict building or a cremation ground. The remaining stages consist of increasingly difficult ascetic practices leading to total control of the senses. After a long hard training the aspirant attains a superhuman body like Shiva's and shares his omnipotence and nature. The Pashupata movement is the only one to link liberation with the attainment of paranormal powers.

Kapalikas and Kalamukhas: These are two extreme Tantric cults, which flourished, from about the 10th to the 13th century, mainly in Karnataka. They were probably off-shoots of the Pashupata movement. They reduced the diversity of creation into two elements - the Lord and creator and the creation that emanated from him.

Unfortunately none of their works are extant Sensational and disparaging allusions are made to them in the Puranas and other literature belonging to the seventh century and later.

According to a few inscriptions and literary references the Kapalikas originated in about the 6th century in the Deccan or in south India. By the 8th century they began to spread northwards; but by the 14th century they had almost died out, their decline being hastened by the rise of the popular Lingayat movement, or perhaps they merged with other Shaivite Tantric orders such as the Kanphatas and the Aghoris.

The Kapalikas (Skull-bearers) were adherents of an ancient ascetic order centred on the worship of the terrifying aspects of Shiva, namely, Mahakala and Kapalabhrit (he who carries a skull) and Bhairava. They were preoccupied with magical practices, and attaining the 'perfections' (siddhis).

All social and religious conventions were deliberately flouted. They ate meat, drank intoxicants, and practised ritual sexual union as a means of achieving consubstantiality with Shiva. The devotees ate from bowls fashioned from human skull and worshipped Shiva. They would carry a triple staff, pot, and a small staff with a skull-shaped top (khat-vanja).

The Kalamukhas flourished in the Karnataka area from about the 11 th to the 13th century. They drank from cups fashioned from human skull as a reminder of man's ephemeral nature, and smeared their bodies with the ashes of cremated corpses.

The teachings of both cults are similar. Both took the 'Great Vow' (mahavrata) whose significance is now unknown, and yoga was mandatory. Human sacrifices and wine were offered to Bhairava and his consort Chandika.

Aghoris: This was a Tantric movement, now extinct, and said to have consisted of two branches-the pure (shuddha) and the dirty (malin). Aghoris were the successors of the Kapalika cult. Among the female divinities worshipped were Shitala, Parnagiri Devi (the tutelary goddess of ascetics) and Kali. Gurus were highly venerated as is usual in Tantrism.

No religious or caste distinctions were allowed, nor was image-worship, and all adherents were required to be celibate. Cannibalism, animal sacrifices and other cruel rites were practised. All kinds of refuse was eaten including excrement (but never horse meat). As excrement is seen to fertilise the soil, so eating it was thought to 'fertilise' the mind and render it capable of every kind of meditation.

The Aghoris led the wandering life of vagabonds. Each guru was accompanied by a dog, as was Shiva in his Bhairava aspect. The Aghori yogins were buried and not cremated, and were believed to be in a state of eternal, deep meditation.

Kanphata Yogis or Gorakhnathis: Gorakhnath, a native of eastern Bengal, reorganised the earlier teaching of this movement. He is identified with Shiva by his followers. Gorakhnath was accredited with great magical and alchemical powers. He synthesised the Pasupata teachings with those of Tantrism and Yoga.

This extreme order of ascetics is characterised bv their split ears (kan 'ear', phata 'split') and huge ear rings of agate, horn or glass, conferred on them at their initiation.

The Yogis practised ritual copulation in graveyards and sometimes cannibalism. The ultimate aim of the devotee is to attain eternal union with Shiva by means of Yogic techniques. Some texts mention 32 yogic positions (asanas), the Shiva Sanhita lists 84, all having magical and hygienic value. Some destroy sickness, old age and death, while other confer spiritual perfections (siddhis).

The 9 nathas and 84 siddhas play an important part in the movement and a lot of folklore is associated with them. Gorakhnath's teaching is universal and hence opposed to caste distinctions. There are few prohibitions concerning food, except that beef and pork are forbidden. But spirits and opium may be consumed and Yogis are allowed to marry.

The dead are buried in the posture of meditation for they are permanently in samadhi, and hence their tombs are called samadh. Representations of the ling, and yoni are placed above the tomb.

Kanphata Yogis officiate in temples dedicated to Bhairava, Sakti or Devi, and Siva. At one time, Gorakhnathis were associated with the Aghons.

Today the Gorakhnathis are in decline both in India and in Nepal where, in the later period of the 18th century, they received royal patronage, Gorakhnath being the clan god of the Gorkha dynasty, who unified Nepal.

Agamantas or Shaiva Siddhantas: This is an important south Indian system of pluralistic realism. It recognises the reality of the world and the plurality of souls. This movement developed partly from the songs of the early Shaiva saints and partly from the fine devotional poetry of the Nayanars (from the 7th to the 10th century).

The four classes of authoritative texts of the cult are the Vedas, the twenty eight Shaiva Agamas, the twelve Timurai, and the fourteen Shaiva Siddhanta Shastras. Although the Vedas are highly regarded, the esoteric Agamas are of greater importance having been revealed by Shiva himself to his devotees. The Siddhanta Shastras were written during the 13th and the early 14th century by a succession of six teachers, most of whom were non-Brahmins and of lowly origin. The Tamil texts and poems include those written by the three great Saiva teachers -Appar, Tirujnana-Sambandhar and Sundaramurti.

The first teacher of Tamil Saivism was Meykantar, (13th century), his work being the Sivujnahodham). But the founder was Aghora Sivacharya.

The Shaiva Siddhanta goal is a state of eternal bliss, the experience of unity-in-duality. Today Shaiva Siddhanta flourishes mostly in Tamil-speaking areas including northern Ceylon.

Kashmiri Shaivism: This is a monistic system, also called the Trika (‘three-fold’) system expounded in Kashmir by Abhinava Gupta (993-1015 AD) who based his exposition on the teachings of earlier sages. He composed a number of commentaries on the now lost Shivadrishti of Somananda, from whom he was fourth in succession. Fortunately, a summary of this work was composed by Utpala, a pupil of Abhinava, entitled the Pratyabhijna Sutras.

However, the earliest teacher was Vasugupta who lived in the 9th century and founded the Pratyabhijna school. He taught that the soul gains knowledge by means of intense yogic meditation. The name Trika refers to the three-fold scripture drawn from the non-canonical Agamas. The system was influenced by Satnkhya, Advaita Vedanta and Pancharatra doctrines.

Initiation in this system is of foremost importance. By means of Shiva's divine grace the aspirant finds a true guru who initiates him. Thus the 'power of activity' (kriyasakti) is awakened in his soul, and this leads ultimately to liberation.

Suddhashaivas or Shivadvaita: A system expounded by Srikanta, it has some features similar to those of Shaiva Siddhanta and Kashmiri Shaivism, as well as some unique characteristics. Srikanta's teaching is based on the Vedantasara. The Supreme Shiva (Para-Shiva) is identified with Brahman - the material and the operative cause of the world.

Liberation is attained by deep meditation on Shiva and this leads to the knowledge that Shiva is identical with the individual self.

Virasaivas: A south Indian devotional cult, also called the Lingayat cult, this was a form of qualified non-dualism, Visishtadvaita. Although the Virasaiva main scriptural text, the Sunyasampadane, does not mention the name Lingayat, it is probable that originally it was an epithet applied to Virasaivas by other cults, because of their concentration on the linga as the only true symbol of divinity.

Basava was the founder, or more probably the systematiser, of the movement. At sixteen he left home and went to the pilgrimage town of Sangama, where he worked to reform Saivism, to overcome caste distinctions and to fight the ban on the remarriage of widows. Later he became a minister of the usurper King Bijjala who reigned at Kalyani. While serving the king he converted a number of Jainas to his cult. But his unorthodox views caused tension between the king and his subjects and he left the king's service. After Basava's death in 1168 AD, the members of his sect were persecuted but today the movement has many followers, mostly in Karnataka and AP.

A model of the linga is presented to each devotee at initiation for daily worship. It is worn in a container round the neck or held in the hand during worship. The Virasaiva initiation replaces the investiture with the sacred thread and this initiation usually takes place during infancy.

Basava taught that all men are temples, and hence they may worship Shiva directly without the aid of priests, ritual sacrifices, fasts or pilgrimages. However, this cult later inaugurated their own priests called jangamas, who are regarded as incarnations of Shiva. The movement has no temples except those erected as memorials. Women have equality with men and may choose their husbands.

Among the things forbidden to cult members are pride, dishonesty, meanness, animal sacrifices, eating meat and drinking intoxicants, astrology, child marriage, sexual licence, and cremation. The last is forbidden because at death the devotee goes immediately to Shiva and is at all times, ensured of his protection. (The dead are buried in a sitting position facing north, unmarried people in a reclining position).

4.3 Shaktism

Although Shaktism and Tantrism were originally two different cultural forces, they are now closely associated. Both are centred on the worship of the supreme goddess Shakti as the feminisation of 'Ultimate Reality' (Brahman). Thus to members of these cults god is conceived as female.

The roots of the Shakti cult go back to the prehistoric 'Earth Cult', the earth being conceived as a religious form which developed into the notion of the earth as the 'Great Mother'. The popular Indian village tutelary goddesses (gramadevatas) are extensions of the concept of the great Mother Goddess. A number of other archaic elements have been assimilated into the 'Great Goddess', some from India's complex tribal cults and others from the Dravidian and Indus civilisations. The fact that Sakti is known by so many names shows her composite nature, which incorporates the functions of many local and tribal goddesses. Although Saktism is closely related with Saivism, it is nonetheless distinguishable from it.

As early as the Rig Veda the goddess Vac represented cosmic energy, later deified as Shakti. Similarly Indra's consort Sachi also personified divine power. The Atharva Veda makes a brief reference to Gnas (literally 'women') which suggests that the powers of nature were associated with female energies long before the advent of Tantric teachings. The Gnas were probably divinities belonging to the vegetal and fertility cults of non-Aryan India.

By the 7th century, in Bengal, a number of local goddess cults, including those of Manasa, Shitala and Chandi (goddess of hunters) had been assimilated into the worship of Kali, who later became identified with Parvati, Siva's consort.

Among Shakti's many names is Durga-Kali. Her cult in Bengal is a mixture of deep devotion, holiness and religious awe coupled with revoltingly cruel blood rites derived from an ancient tribal cult.

When signifying abstract time, Durga-Kali is called Adisakti-the primordial active female principle in which no duality exists and all opposites are reconciled.

As Time (Kala) does not exist until the Goddess manifests herself, she is called the 'mother of time' (Kalamata). As the embodiment of entire creation she is Mahakali; as destroyer of worlds and of Time she is Kalaharshini. Whateve name or form she assumes, her quintessence remains unchanged.

The lunar aspect of Kali-Durga symbolises astro-cosmic totality, and hence she may be depicted iconographically with sixteen arms, signifying the sixteen digits of the moon, which correspond to the Vedic belief that the universe is made up of sixteen parts.

When Shakti is portrayed with Shiva as his consort, her aspect is beneficent and she is called Parvati, Devi or Uma (the embodiment of ideal womanhood), or Mahadevi (the great goddess). The eternal blissful union (samarasya) of Shiva and Shakti is the basis of the 'realistic monism' of the Shakti and Shaiva cults.

4.4 Tantrism

This is a form of sacramental ritualism, having a number of esoteric and magical aspects, which employs mantras, yantras and yogic techniques. Tantric elements also feature in Jainism, Mahayana Buddhism, Shaivism, Vaishnavism and Shaktism.

The name Tantrism is derived from the sacred texts called Tantras. The earliest works of this vast literature were written during the Gupta period. To Tantrists, the Tantras are as authoritative as the Vedas and hence are known as the 'Fifth Veda'.

Tantrism developed primarily in north-west India along the Afghan border and in western Bengal and Assam, all only slightly 'Hinduised' areas of the subcontinent, and hence many non-Aryan features were included.

Initiation (diksha) and the receiving of a specific mantra from a qualified guru is all important in the Tantric cults. The initiate is 'reborn' and given the necessary esoteric knowledge to guide him towards liberation. New forms of asceticism were developed, including the sublimation of sexual union in imitation of the union of Siva and Sakti.

Great power is said to result from the worship of Shakti, but from the philosophical point of view the emergence of the Goddess is the result of the low level of spirituality. Hence only 'sexuality' can be utilised to attain transcendence.

Tantrism has two main divisions-the so-called left-hand' (vamachara) cult and the 'right-hand' (dakshinachara) cult. The practices of the dakshinachara are not as extreme as those of the vamacharis, and their rites, although similar to the vamachara, are never performed physically but only symbolically. Neither cult recognises caste distinctions and all aspirants have to undergo complex initiatory rites. The vamachara adepts deliberately flout all the social rules and prohibitions of Hinduism under ritual conditions, in an attempt to free themselves from the limitations of mundane existence and so attain greater spiritual power.

Initially the erotic and esoteric aspects of Tantrism were intended only for the fully initiated use as liberating techniques. In Tantric ritual copulation the female partner (who incorporates Shakti) should be worshipped with deep devotion, and the sexual rites performed without losing one's purity, keeping one's mind uninvolved. In the highest form of Tantric meditation the female generative organ (yoni) symbolises the universal womb, the source of all existence. When liberated, the souls merge with the cosmic essence in the joy of pure consciousness.

Yantras, geometric symbolic patterns having great spiritual significance, are also employed. They are equivalent to the concrete personal expression of the unapproachable Divine. Yantras operate in the visible sphere as mantras do in the audible. By means of yantras devotees are able to participate ritually in the powers of the universe. The best known is the sriyantra consisting of a number of interlocking triangles with a central point (bindu) symbolising the eternal, undifferentiated principle (Brahman).

The Sahajiya Tantrists reject the use of mantras, texts, images, and meditation, since only shunya is one's true nature. The difficulty in defining shunya, and its metaphysical ambiguity, encouraged many extreme sexual excesses.