Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - being learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

India - the physical setting

1.0 INTRODUCTION

India is the largest country in the Indian subcontinent, deriving its name from the river Indus which flows through the northwestern part of the country. Earlier, the undivided Hindustan included many other modern day nations too.

2.0 INDIA - PHYSICAL FEATURES

Indian mainland extends in the tropical and subtropical zones from latitude 8°4' north to 37°6' north and from longitude 68°7' east to 97°25' east. The southernmost point in indian territory, the Indira Point (formerly called Pygmalion Point), is situated at 6°30' north in the Nicobar Islands. The country thus lies wholly in the northern and eastern hemispheres. The northernmost point of India lies in the state of Jammu and Kashmir and it is known as Indira col. (a col in the geographic sense is a geomorphological term referring to the lowest point on a mountain ridge between two peaks)

India is bounded to the southwest by the Arabian Sea, to the southeast by the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean to the south. Kanyakumari constitutes the southern tip of the Indian peninsula, which narrows before ending in the Indian Ocean. The southernmost part of India is Indira Point in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.The Maldives, Sri Lanka and Indonesia are island nations to the south of India with Sri Lanka separated from India by a narrow channel of sea formed by Palk Strait and the Gulf of Mannar. The territorial waters of India extend into the sea to a distance of 12 nautical miles (13.8 mi; 22.2 km) measured from the appropriate baseline.

The northern frontiers of India are defined largely by the Himalayan mountain range where its political boundaries with China, Bhutan, and Nepal lie. Its western borders with Pakistan lie in the Punjab Plain and the Thar desert. In the far northeast, the Chin Hills and Kachin Hills, deeply forested mountainous regions, separate India from Burma while its political border with Bangladesh is defined by the watershed region of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, the Khasi hills and Mizo Hills. The Ganges is the longest river originating in India and forms the Indo-Gangetic Plain. The Ganges-Brahmaputra system occupies most of northern, central and eastern India, while the Deccan Plateau occupies most of southern India. Along its western frontier is the Thar Desert, which is the seventh-largest desert in the world.

2.1 Area and boundaries

India stretches 3,214 km at its maximum from north to south and 2,933 km at its maximum from east to west. The total length of the mainland coastline is nearly 6,100 km and the land frontier measures about 15,200 km. The total length of the coastline, including that of the islands, is about 7500 km. With an area of about 32,87,782 sq km, India is the seventh largest country in the world.

Accounting for about 2.4 per cent of total world area. Countries larger than India are Russia, Canada, China, USA, Brazil and Australia. In terms of population, however, India is second only to China.

India's neighbours in the north are China (Chinese Tibetan Autonomous Region), Nepal and Bhutan. The boundary between India and China is called the MacMahon Line. To the northwest India shares a boundary mainly with Pakistan and to the east with Myanmar, while Bangladesh forms almost an enclave within India. Afghanistan is another close neighbour of India towards northwest. The country is shaped somewhat like a triangle with its base in the north (the Himalayas) and a narrow apex in the south (Kanyakumari). South of the Tropic of Cancer the Indian landmass tapers between the Bay of Bengal in the east and the Arabian Sea in the west. The Indian Ocean lies south. The Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea are its two northward extensions. In the south, on the eastern side, the Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait separate India from Sri Lanka. India's Islands include the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal and the Laccadive (Lakshadweep), Minicoy and Amindive Islands in the Arabian Sea.

India and its neighbours Pakistan, Nepal, and Bhutan are known as the Indian sub-continent, marked by the mountains in the north and the sea in the south. This term indicates the insularity of this region from the rest of the world.

India’s official position is clear : all claims by Pakistan and China on any of its territory in J&K are wrong and mischievous. Entire state of J&K is undisputed Indian territory.

2.3 Administrative divisions

At the time of independence in 1947, India was divided into hundreds of small states and principalities. These states were united to form fewer states of larger size and finally organised in 1956 to form 14 states and six union territories. This organisation of Indian states was based upon a number of criteria, the language being one of these. Subsequent to this a number of new states have been carved out to meet the aspirations of the local people and to meet the developmental goals. Presently there are 29 States, six Union Territories and one National Capital Territory. Telangana is the newest state of India.

3.0 Geology

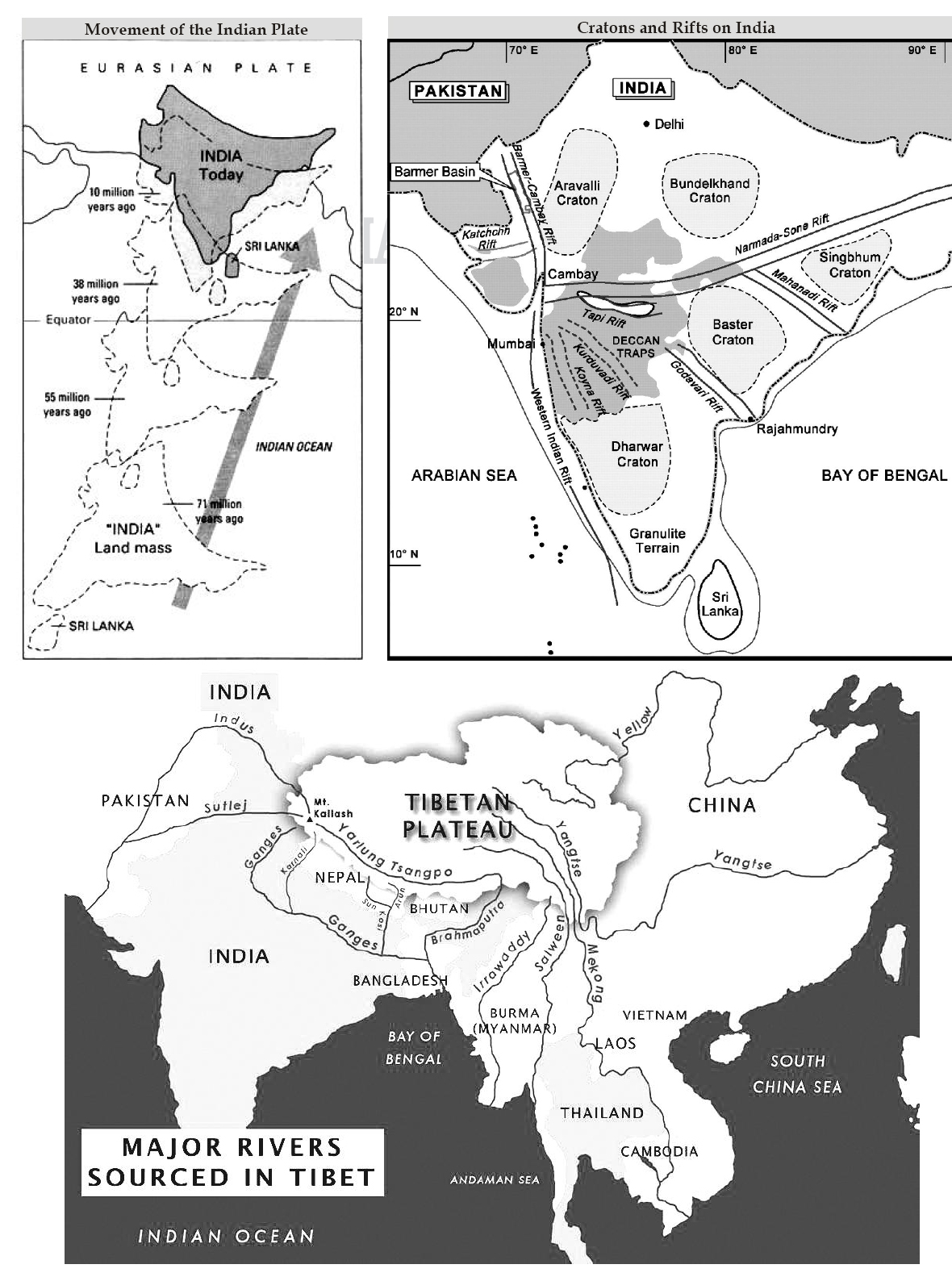

The geological history of India is very complex. The rocks in different parts of the country range in age from very ancient to geologically recent formations. The peninsular block of India is the area where some of the oldest rocks of the world are found. The rocks forming the Himalayan region and the northern plains on the other hand are of a recent origin. Peninsular India is believed to be a part of the ancient Gondwanaland. From the point of geological history, this part of India bears a close association with parts of South Africa and Australia. Though the rocks found on the surface of the peninsular plateau in many parts are of sedimentary origin (for example in the northern part), the basement of this tableland is made up of crystalline rocks. This ancient crystalline rock mass is thought to have collided with the southern shore of the Asian landmass, causing the uplift of the Himalayas. The great plain of northern India has been formed through deposition of alluvium by the rivers flowing down from the Himalayan region. This plain is not only one of the youngest parts of India geologically, but also one of the world's largest stretches of alluvium. This is also one of the most fertile and hence one of the most densely populated areas of the world.

It is customary to divide India into three landform regions - (1) the Himalayas and the associated ranges; (2) the Indo-Gangetic plain to the south of the Himalayan region; and (3) the peninsular plateau to the south of the plains. These three landform regions have experienced different geological processes and sequences of events.

3.1 The Himalayas and the associated ranges

The Himalayas and the associated ranges to the north are made up primarily of Proterozoic and Phamrozoic sediments that are largely of marine origin and they experienced great tectonic disturbances. These mountains have resulted from diastrophic movements during comparatively recent geological times. The rocks in these mountain ranges are highly folded and faulted. The geological evidence that is available in abundance suggests that this extra-peninsular region has remained under the sea for the greater part of its history and therefore has layers of marine sediments that are characteristic of all geological ages subsequent to the Cambrian period.

3.2 The Indo Gangetic plain

The Indo-Gangetic plain, as stated earlier, is geologically a very young feature of the country. This plain has been formed only during the Quaternary Period. The region has very limited relief and much of the surface of the plain is below 300 metres above the sea level. This unit consists of typical undulating plains created by highly developed drainage systems. The surface of the plains is covered by sediments of Holocene or recent age. The western part of the plain is occupied by the vast stretches of desert.

3.3 The Peninsular plateau

The peninsular plateau is geologically as well morphologically a totally different kind of area from the former two units. According to the available geological evidence, the peninsular region has since the Cambrian period been a continental part of the crust of the earth. It is a stable mass of Pre-Cambrian rocks some of which have been there since the formation of the earth. In fact this is a fragment of the ancient crust of the earth. This region has never been submerged beneath the sea since the Cambrian period, except temporarily and that too locally. The interior of the peninsular plateau has no sediments of marine origin dating back to period younger than Cambrian. During their long existence the rocks of this region have undergone little structural transformation. Among the few Phenerozoic events that have affected the peninsular block include the sedimentation during the Gondwana times of the Mesozoic era along with outpourings of the Deccan lavas. Though the topography of this region is also rugged like that of the Himalayan region but in an entirely different way. The mountains of the peninsular region, except for the Aravallis, do not owe their origin to tectonic forces but to denudation of ancient plateau surfaces. They are thus relict features of the old plateau surface that have survived weathering and erosion for a long time. From a geomorphological point of view they can be considered as tors of the extensive plateau. The only impact of tectonic movements on the rock strata in the peninsular region has been fracturing and vertical and radial displacement of the fractured blocks. The rivers flowing over this plateau surface have flat, shallow valleys with very low gradient and most have attained their base level of erosion. (A tor is a large, free-standing rock rising abruptly)

4.0 PHYSIOGRAPHY

Diverse in its physiography, India can be divided into three units: the mountains in the north, the plains of northern India and the coast, and the plateau region of the south. The coastal plains are sometimes also considered a separate unit.

4.1 Himalayas (Sanskrit, hima (snow) + alaya (dwelling), literally, "abode of the snow”)

The Himalayas are one of the youngest fold mountain ranges in the world and comprise mainly sedimentary rocks. They, along with the associated ranges in the northwest and northeast, form the northern boundary of India, extending from Jammu and Kashmir in the west to Assam, Manipur and Mizoram in the east. The total length of this chain is about 5000 km, of which about 2500 km stretches in the form of an arc along the Indian border. The Indus Valley and Brahmaputra Valley are taken as the western and eastern limits, respectively, of the Himalayas within India. The breadth of the Himalayan mountains varies from 150 to 400 km and the average height of the whole region is taken as about 2000 metres. The elevation of the Himalayan chain more or less decreases eastward.

Himalayas are believed to have been formed during the Tertiary Era in the zone formerly called the Tethys Sea, a geosyncline situated between the Gondwanaland to the south and the Angaraland to the north. According to this view the two blocks of landmass collided with each other and the sediments laid in the Tethys were compressed and folded to form the Himalayas. This theory explains the formation of the Himalayas as a result of inter-continental collision.

The theory of plate tectonics, however, emphasises the concept of intra-plate folding. According to this theory, the Indian Plate or the Gondwanaland moved northwards and its forward edge penetrated below the southern edge of the Tibetan Plate. The obstruction caused by the Tibetan Plate to the northward movement of the Indian Plate led to the folding of the later plate and the Himalayas came into existence. Penetration of the edge of the Indian Plate below the edge of the Tibetan Plate led to uplift of the Tibetan region in the form of a plateau. There is evidence that the Indian Plate is still moving northwards at an imperceptible rate which is responsible for frequent earthquakes in the Himalayan region.

4.1.1 Major ranges of the Himalayas

The Himalayas comprise a number of almost parallel ranges. As pointed out earlier, the westernmost and the easternmost limits of the Himalayas proper in India are marked by the Indus Valley and the Brahmaputra Valley, respectively. The mountainous region to the west of the Indus Valley is often called the Trans-Himalayas while the hilly region to the east of the Brahmaputra Valley is called Purvanchal or Purvachal. Generally three major ranges are identified within Himalayas.

The Greater or the Inner Himalayas (Himadri):This range is also called the Central Himalayas. This is the northernmost range of the Himalayan system and it is also the highest. About 25 km broad, it is the source region of many rivers and glaciers and its mountains reach an average height of 6000 metres. Mount Everest or Sagarmatha, the highest mountain peak in the world (8848 metres) lies in this range. The other important peaks of this range are: Kanchenjunga (8598 metres), Makalu (8481 metres) and Dhaulagiri (8172 metres). The south facing slope of the Greater Himalayan range is steeper than the northern slope. Grantie, gneiss and schist are the chief rocks forming this range. Most of these rocks have been metamorphosed due to extreme compression and folding.

The Lesser Himalayas (Himachal): This range extends to the south of the Central Himalayas. It is also known as the Middle Himalayas. This range is broader than the former range but its height is lower. Average height of mountains here is about 1800 metres and the breadth varies from 80 to 100 km.

According to most observers, this range was uplifted at a slow rate and the rivers rising from the Greater Himalayas have cut deep gorges in this section. The Main Central Thrust Zone lies between this range and the Central Himalayas. Dhauladhar, Nag Reeva, Pir Panjal and Mahabharta are the important ranges in this zone. Slate, Limestones and quartzites are the dominant rocks.

The Sub-Himalayas (Shivaliks): This is the third and the lowest range of the system, lying further south of the former two ranges. This range is also known as the Outer Himalayas. The Main Boundary Thrust separates this range from the Lesser or the Middle Himalayas. The length of this range between the Potwar Basin in the west and the Teesta River in the east is about 2400 km. The breadth of the Shivalik range varies between 10 and 50 kilometres and its average height is about 1,200 m. The newest range of the Himalayas, it separates the plains from the alluvium filled basins called duns and duars. The Himalayan Frontal Fault marks the boundary between the Shivalik and the alluvial plains to its south. This range has been formed most recently and the rocks in this zone have been derived from the debris deposited by the Himalayan rivers and glaciers. The Siwalik range extends only in the western part of the Himalayas and in the eastern part this range is believed to have been eroded and buried in alluvium. Due to this fact the high mountain ranges appear to be rising abruptly from the plains in the eastern part.

Tibetan Himalayas: North of the Great Himalayas lie the Trans-Himalayas or the Tibet Himalayas. This range acts as a watershed between rivers flowing to the north and those flowing to the south. Tibetan Himalayas is about 40 km wide and rises to heights of 3,000 to 4,300 metres. The rocks in this range are highly fossiliferous ranging in age from Cambrian to Tertiary. This range is separated from the Eurasian Plate by the Indus-Tsangpo Suture Zone.

There are also some minor ranges in the Himalayan system. They include the Karakoram (highest peak- K2), Zaskar and Laddakh ranges in the west, and the Garo, Khasi, Jaintia, Lushai and Pathkai ranges in the east. The hilly region to the east of Brahamaputra Valley is often called Purvanchal.

4.1.2 Regional divisions of Himalayas

The most fundamental of regional divisions of Himalayas divides this mountain system into two parts, the Western Himalayas and the Eastern Himalayas. The western part of the Himalayas is considered the dry region while the eastern part is the humid region. These two divisions of the Himalayas are identified rather arbitrarily. According to a more logical regional division the mountain region is divided into the following units.

Punjab Himalayas: This part of the Himalayas stretches between the River Indus and River Sutlej. It is the westernmost part of the region. This stretch measures 562 km from west to east.

Kumaon Himalayas: The Kumaon Himalayas extend between the rivers Sutlej and the Kali. This stretch measures about 320 km and it lies to the east of the Punjab Himalayas.

Nepal Himalayas: This part of the Himalayas extends between the rivers Kali on the west and the Teesta to the east. The stretch measures 800 km. The highest peaks of the Himalayas lie in this zone.

Assam Himalayas:This is the easternmost part of the Himalayas and its western and eastern boundaries are marked by the rivers Teesta and the Brahamaputra, respectively. This stretch measures about 750 km. The height of the mountains in this zone is the least.

Himalayas are an important physical unit of India. This mountain region not only forms aphysical border to the north of the country, it also acts as a climatic divide. It also forms a major watershed between India and China. Apart from being the source of a large number of rivers, the Himalayas are also the source of numerous glaciers. This area is the largest snow-field outside the polar regions.

4.2 The Plains of India

This unit includes both the plains of northern India and the coastal plains. The northern plain is largely alluvial in nature and the westernmost portion of it is occupied by the Thar Desert. The coastal plains stretch along the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea coasts and these plains are also alluvial to a large extent.

4.2.1 The Northern Plain

The northern plain is also known as the Ganga-Brahmaputra plain and the Indo-Gangetic Plain. The rivers of the Indus, Ganga and Brahmaputra systems have contributed to the formation of this plain. The westernmost part of this plain is called the Indus or the Punjab plain. It covers the areas of Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan and the slope of this plain is towards west and southwest. The Indus plain of Pakistan is the westward extension of this plain. The central part of the northern plain is generally called the Ganga Plain and the general slope of this part is towards east. This unit accounts for the largest area of this plain in India. The easternmost part of the great plain is called the Brahmaputra Plain. Slope of this part is towards west and south and this plain converges with the Ganga Plain in Bangladesh.

It is also customary to divide the northern plain into regional units such as the western plain, eastern plain, Bihar plain, Bengal plain and Assam plain. The whole plain is a combination of flood plains in the west and flood plains and delta plains in the east. A further division of the Ganga Plain into khadar and hangar areas is also very common. The term khadar is applied to areas of new alluvium where a new layer of silt is deposited regularly during floods. These areas stretch along the river channels. The soils in these areas are sandy and the water table is generally high.

The term bangar is applied to areas of old alluvium that are farther from the river channels and generally out of reach of frequent floods. The soils in these areas are finer than in the khadar and the water table in these parts is generally lower. The southeastern part of this plain is called the Sunderban Delta. This delta has been formed by the Ganga and the Brahmaputra and a large part of it extends in Bangladesh. The northern part of the Ganga Plain along the Himalayan foothills is called the terai zone. This is largely a marshy area. Much of the marsh land has now been reclaimed for farming.

4.2.2 The Coastal Plains

The coastal plain stretching along the Bay of Bengal coast is called the Eastern Coastal Plain while the one stretching along the Arabian Sea coast is called the Western Coastal Plain. The eastern coastal plain, also known as Coromandel Coastal Plain, is divided into the Utkal Plain, Andhra plain and Tamil Nadu plain. This plain is occupied by the delta regions of rivers Mahanadi, Godavari, Krishna and Kaveri. It is a broad fertile coastal lowland.

The western coastal plain extends from Gujarat in north to Kerala in south. Unlike the eastern coastal plain, this plain is rather narrow except for in Gujarat where it is the widest. The northern part of the plain is occupied by the Gujarat plain. South of Gujarat up to Goa stretches the Konkan coastal plain. The southern part is occupied by the Malabar coastal plain and Kerala coastal plain. The chief reason for a lesser breadth of the western coastal plain is a general lack of the delta formation by the rivers flowing into the Arabian Sea from the peninsular plateau. Most of these rivers flow rapidly over a rather steep slope and form estuaries. Another reason for the lesser breadth of this coastal plain is the fact that the western coastline of India a coastline of submergence unlike the eastern coastline which is a coastline of emergence. From agricultural point of view the eastern caostal plain is more important than the western coastal plain.

4.3 Peninsular Plateau

The peninsular plateau or peninsular India is the name given to the area spreading to the south of the Indo-Gangetic plain and flanked by sea on three sides. This plateau is shaped like a triangle with its base in the north. The Eastern Ghats and the Western Ghats constitute its eastern and western boundaries, respectively. The River Narmada, which flows through a rift valley, divides the region into two parts: the Malwa Plateau in the north and the Deccan Plateau in the south. The Aravallis and the Chhota Nagpur Plateau lie to the west and east, respectively, of Malwa Plateau. The general slope of land of this part is towards north and the rivers rising in this part flow northwards and join rivers of Ganga system. Rivers Chambal, Son and Damodar are examples of these rivers. Though most of the rocks in the plateau region are very old, the lava rocks are generally not visible in this part. The rock systems of the peninsular plateau region extend towards northeast up to the Meghalaya Plateau. The Chhota Nagpur Plateau and the Meghalaya Plateau are separated by a trough that has been filled with alluvium by rivers of the Ganga and Brahmaputra systems. The ancient rocks of the peninsular region extend northwards under the northern plains.

The Aravallis act as an important climatic divide in the northwestern part of the plateau region. While the area to the east of the Aravallis is considered a semi-arid region the area lying to the west of this mountain system in Rajasthan and Gujarat is a desert. This desert region extends westwards into Pakistan. The southern part or the Deccan Plateau is divided into three major units, the Western Ghats, the Eastern Ghats and the Deccan Trap. Deccan Trap represents the core of the plateau region and it is in this part that the oldest rocks of India are found. This region is made up of crystalline rocks. The Western Ghats form a major water divide in the Deccan Plateau region and the rivers rising from the eastern slope of these ghats flow towards the Bay of Bengal. The Godavari, the Krishna and the Cauvery all rise in the Western Ghats and flow across the Deccan Plateau into the Bay of Bengal. The Narmada and the Tapi flowing through rift valleys are the only major exceptions to this generalisation. The rivers rising on the western slopes of the Western Ghats are short turbulent streams flowing over the steep western face of the ghats into the Arabian Sea. The Western Ghats separate the Deccan Trap region from the Western Coastal Plain while the Eastern Ghats lie between the Eastern Coastal Plain and the Deccan Trap. The Western Ghats are in the form of a continuous range from south to north. The highest range of the Western Ghats is named Sahyadri. The Eastern Ghats on the other hand are formed by a series of discontinuous hill ranges with gaps through which the rivers of the peninsular region flow into the Bay of Bengal. The Western Ghats are connected to the Eastern Ghats by the Nilgiri Hills (Blue Mountains). To the south of the Nilgiri Hills lie the Annamalai Hills (Annaimudi is the highest peak in the peninsular region) which are separated from the former by the Palghat Pass. Two branches of the Annamalai Hills are known as the Palani Hills and the Yelagiri (Cardamom) Hills. Many rivers of the Western Ghats make waterfalls. The Sivaaamudram Fall, the Gokak Fall and the Mahatma Gandhi Fall are important waterfalls in this area. The plateau region includes a number of other minor mountains besides the Aravalli and the Eastern and Western Ghats. They include the Vindhyas and Satpuras in Central India. The Satpuras, which lie between the rivers Narmada and Tapi, have several hills, including the Rajpipla Hills in Maharashtra, and the Maikal Range and Pachmarhi Hills in Madhya Pradesh. Dhupgarh (Dhoopgarh), near Panchmarhi, is the highest peak in central India.

4.4 Islands of India

There are 247 islands in India, out of which there are 204 islands in the Bay of Bengal and 43 islands in the Arabian Sea. There are a few coral islands in the Gulf of Mannar also. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal consist of hard volcanic rocks. The middle Andaman and Great Nicobar Islands are the largest islands of India. Lakshadweep islands in the Arabian Sea are formed by corals. The southern-most point of India is in the Greater Nicobar Island. It is called Indira Point (formerly it was called Pygmalion Point), now submerged after the 2004 tsunami.