Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - begin learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

Indian patent law and the Pharma industry

1.0 INTRODUCTION

The trade related intellectual property rights agreement (TRIPS) governed by the WTO has established a framework of intellectual property laws. These include patents, copyrights, trademarks, geographical indicators, protection of undisclosed information, layout designs of integrated circuits, and industrial designs. The area for protection that is interesting for India is the protection of traditional knowledge as intellectual property. Several pros and cons have been considered for agreement on trade related aspects of intellectual property rights. The April 15, 1994, Marrakesh agreement establishing the World Trade Organization (WTO Agreement), states that "patents shall be available for any inventions, whether product or process, in all fields of technology provided that they are new, involve an inventive step, and are capable of industrial application".

A patent is a government granted exclusive right, or a set of specified rights, to an inventor, or a person who claims to be the true and first inventor (or the discoverer of a new process) to make, use or sell an invention, usually for a specified term.

A patent for an invention is the grant of a property right to the inventor, issued by the Patent and Trademark Office (PTO). Patents are used to protect new product, process, apparatus, and uses providing the invention is not obvious in light of what has been done before, is not in the public domain, and has not been disclosed anywhere in the world at the time of the application. The invention must have a practical purpose.

Patents are registrable nationally. Registration provides a patentee the right to prevent anyone making, using, selling, or importing the invention for 20 years from the date on which the application for the patent was filed or, in special cases, from the date an earlier related application was filed, subject to the payment of maintenance fees. Patents are enforced by court proceedings. In addition, the Regulation on Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs), grants "patent extensions" of up to 5 years to pharmaceutical and plant products, providing as much as 25 years of patent life for originator medicines.

Patents of living organisms, that can include plant and animal species, and related biological and biotechnology-enabled inventions, are classified as patents on life forms, or bio-patents.

2.0 IPR IN INDIA

The objective of patent policy in India in 1950 was to ensure local production of drugs. At that time foreign multinationals made the entire drugs supply in India. Foreign multinationals controlled more than 90% of the Indian pharmaceutical industry and hence determined supply and availability of drugs. Drugs were manufactured outside India and imported at a higher cost. The cost of drugs in India was amongst the highest in the world. The drug prices were so high that in 1961, the US senate committee headed by Senator Estes Kefauver observed that India ranked among the highest priced nations in the world for drugs.

Statistics of the first five year plan revealed that income from industries was as low as a mere 6.6% of the total national income. A mere 8% of the total labour force was working in the Indian industrial establishment. Epidemic diseases accounted for 5.1% of the total mortality. The first five-year plan recorded that India was the largest reservoir of epidemic diseases. Poverty was also at its peak in India. Consequent to a disastrous British Raj, around 50% of India's population were living under poverty and were unable to afford the cost of drugs. Consequently, life expectancy was very low and mortality rate due to diseases was very high. The central government under the Drugs Act of 1940 imported required drugs.

To remedy this situation the government of India took two initiatives. First, the government signed an agreement with UNICEF to set up a factory for manufacturing of penicillin and other antibiotics. This resulted in the establishment of Hindustan Antibiotic Limited in 1957 to manufacture drugs at a cheaper rate for the public. Next, the government appointed justice Rajagopala-Ayyangar Committee in 1957 to recommend revision to the patent law to suit industrial needs. The object of the committee was to ensure India developed a locally sustainable pharmaceutical market. The committee submitted its report in 1959.

In recommending changes, the Ayyanger Committee was bound by the provisions of the Indian constitution. Article 21 of the constitution guarantees right of life, which include the right to good health. The preamble of the Constitution requires policies to balance social and economics rights. Hence public health concerns need to be weighed with business interests in amending the patent legislation. The Ayyanger report argued that a patent policy vesting unrestrained monopoly would deny a vast section of India's population from access to medicines.

The report concluded that a policy with unfettered monopoly rights would violate the preamble of the Indian Constitution. The report studied the patent systems of U.K., Germany and the U.S. and pointed that Germany's weakened patent protection encouraged the growth of chemical industry. Hence the report recommended a compulsory licensing system and process patenting of drugs. The act based on the Ayyanger report and the rules came into force in 1972. Since healthcare was a major concern, the Drug Price Control Order was also passed in 1970. The order gave control over the price of drugs to the government thus complimenting the compulsory license provisions in the Indian legislation. After the Drug Price Control Order was passed, the government of India placed most drugs under price control.

The economic brunt of the 1970 patent policy has not escaped India. Multinational companies, once major players, became reluctant to sell in India. By 1997, multinationals accounted for less than 30 percent of bulks and 20 percent of locally produced formulations. Most multinational complied with the minimum requirements necessary to maintain presence in the Indian market (such as producing simple formulations from imported bulks), while awaiting stronger patent protection. The government responded by steadily reducing price control on drugs. In 1970 most drugs were under price control, by 1984 this was reduced to 347 drugs, and to 163 drugs in 1987. In 1994 only 73 drugs remained under price control.

There was a lot of debate in India about joining the Paris Convention in 1986. The Indian Drug Manufacturers Association (IDMA) was at the forefront of the debate highlighting the risks of joining the Convention before India eventually relented to severe international pressure. During that time the IDMA was said to have been advised by retired judges and had a lot of support from the judiciary as well.

India was very actively involved in opposing the TRIPS component of the GATT agreement, especially the proposal for product patents on pharmaceutical innovations. Indira Gandhi succinctly summed up the national sentiment at the World Health Assembly in 1982: "The idea of a better-ordered world is one in which medical discoveries will be free of patents and there will be no profiteering from life and death." India then signed the treaty, and though most unwillingly, it was committed to introducing pharmaceutical product patents 2004, and hence a cost-benefit analysis of this move is essential for India.

3.0 The revolution in Indian pharmaceutical sector

The patent policy of 1970 dramatically changed India's condition. In 45 years, the Indian pharmaceutical industry size is around $ 20 billion, compared to a mere USD 2.1 million before 1970. Currently branded generics dominate the market, making up nearly 70 to 80 percent of the market. India is the biggest supplier of generic drugs worldwide, with upto 20% of global supply coming from India. India’s biotechnology industry India's biotechnology industry comprising bio-pharmaceuticals, bio-services, bio-agriculture, bio-industry and bioinformatics is expected grow at an average growth rate of around 30 per cent a year and reach US$ 100 billion by 2025. Biopharma, comprising vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics, is the largest sub-sector contributing nearly 62 per cent of the total revenues at Rs 12,600 crore (US$ 1.9 billion). Of the 465 bulk drugs used in India, approximately 425 are manufactured within the country. Indian industry has emerged as a world leader in the production of several bulk drugs. Indian industry has emerged as a leader for the production of bulk drugs like sulphamethoxazole and ethambutol. Indian production accounts for nearly 50% of the world production.

Other than developing indigenous pharmaceuticals, India has grown as a major player in the international generic drugs market. The U.S., during the Anthrax scare, considered importing cheap generic drugs from India. India emerged as a reliable exporter of the generic AIDS drugs in South African AIDS crises. Some other examples - the cost of ciprofloxacin was Rs. 27 (60 cents) per tablet ten years ago in India. The cost of ciprofloxacin currently is Rs. 1.50 (4 cents). Indian drug-makers export the generic version of ciprofloxacin to Russia, Brazil, Southeast Asia and Middle East at highly competitive prices.

The drugs and pharmaceuticals sector attracted cumulative FDI inflows worth US$ 13.32 billion between April 2000 and September 2015, according to data released by the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP). The Government of India unveiled 'Pharma Vision 2020' aimed at making India a global leader in end-to-end drug manufacture. Approval time for new facilities has been reduced to boost investments. Further, the government introduced mechanisms such as the Drug Price Control Order (DPCO) and the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority (NPPA) to deal with the issue of affordability and availability of medicines. In spite of such an aggressive development of the indigenous pharmaceutical industry, only a mere 30% of Indian population has secure access to modern medications. Until the entire population has access to drugs India has to follow the pre-TRIPS patent policy.

INDIAN PHARMA SECTOR

- Indian pharmaceutical sector industry supplies over 50 per cent of global demand for various vaccines, 40 per cent of generic demand in the US and 25 per cent of all medicine in UK.

- India contributes the second largest share of pharmaceutical and biotech workforce in the world. The pharmaceutical sector in India was valued at US$ 33 billion in 2017.

- India's domestic pharmaceutical market turnover reached Rs 129,015 crore (US$ 18.12 billion) in 2018, growing 9.4 per cent year-on-year (in Rs) from Rs 116,389 crore (US$ 17.87 billion) in 2017. In February 2019, the Indian pharmaceutical market grew by 10 per cent year-on-year.

- With 71 per cent market share, generic drugs form the largest segment of the Indian pharmaceutical sector.

- Based on moving annual turnover, Anti-Infectives (13.6%), Cardiac (12.4%), Gastro Intestinals (11.5%) had the biggest market share in the Indian pharma market in 2018.

- Indian drugs are exported to more than 200 countries in the world, with the US as the key market.

- Generic drugs account for 20 per cent of global exports in terms of volume, making the country the largest provider of generic medicines globally and expected to expand even further in coming years.

- India's pharmaceutical exports stood at US$ 17.27 billion in FY18 and US$ 17.15 billion in FY19. In FY18, 31 per cent of these exports from India went to the US.

- The 'Pharma Vision 2020' by the government's Department of Pharmaceuticals aims to make India a major hub for end-to-end drug discovery.

- The sector has received cumulative FDI worth US$ 15.93 billion between April 2000 and December 2018. Under Budget 2019-20, allocation to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare increased by 13.1 per cent to Rs 61,398 crore (US$ 8.98 billion).

- Indian pharmaceutical sector is expected to grow at a CAGR of 15 per cent in the near future and medical device market expected to grow $50 billion by 2025.

3.1 TRIPS Patent Policy

TRIPS patent policy requires developing countries to only award product patents. Novel processes will not be patentable in developing countries since these countries do not use process by product claims. Consequentially, inventions patentable in developed nations by use of process by product claim will fall outside TRIPS compliant patent legislation of developing nations. Some generic drugs patentable in developed nation using process by product claim will be unprotected in developing nations.

TRIPS, the intellectual property component of the Uruguay round of the GATT Treaty, have given rise to an acrimonious debate between the developed countries and less developed countries (LDCs). Business interests in the developed world claimed large losses from the imitation and use of their innovations in LDCs. They also asserted that IPRs would benefit the developing countries like India by encouraging foreign investment, by enabling transfer of technology and greater domestic research and development (R&D). On the other side, LDC governments were worried about the higher prices that stronger IPRs would entail and about the harm that their introduction might cause to infant high tech industries.

The Indian drug manufacturers vehemently opposed the concept of exclusive marketing rights. They maintained that exclusive marketing rights (EMR) would lead to the destruction of the local drug industry and that it was more restrictive than even the product patent regime. They argued that foreign drug companies would get the right for exclusive marketing in India before going through an examination in India. It was also feared that the Indian drug companies would be driven out of business.

4.0 The 2005 Amendments

In March 2005, India's Parliament approved patent regulations to stop local drug makers from copying new drugs developed by other, primarily Western companies. The new law, amending India's 1970 Patent Act, affects everything from electronics to software to medicines, and has been expected for years as a condition for India to join the World Trade Organization. It is widely believed that the 2005 amendments were made mainly due to international pressure, as the World Trade Organization ("WTO") demanded that India observe international drug patents. In 1995, the WTO's Trade-related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement was reached in Marrakesh, Morocco, where India, along with many other countries, agreed to grant 20-year patents on pharmaceutical products from January 1, 2005. The new WTO regime effectively outlawed the generic production of new medicines.

Previously, companies could copy drugs discovered or invented by other companies by tweaking the processes used to make them. As an executive of a leading Indian company puts it: "The winner used to be the guy who could copy faster. Now that has completely changed so that companies that don't innovate will die, especially in the pharmaceutical industry".

The new patent system recognizes registered original drugs as products no matter how they are produced, thus making it illegal to copy drugs still under patent. Also, it appears that the 2005 amendments have done away with the practice of "evergreening" of pharmaceutical patents, where patent owners allegedly try to extend patent life through grant of new patents by minor "innovations" or improvements on formulations, dosage forms or minor chemical variations of an earlier patented product. However, the new law also makes it clear that any invention that enhances the known efficacy of the substance or results in a new product or employs at least one new reactant is patentable and that only the mere discovery of a new form or of any new property or new use of a known substance or process is excluded. It may not be too difficult to prove that the improved dosage form is more efficacious or that one new reactant is involved in the known process to make the product.

These amendments to India's patent law have sparked worries that Indian companies will face tough global competition, and that the cost of medicines would jump in poor countries now supplied by Indian generic drugs. Since 2000, the gathering momentum of the global popular outrage against a tighter patent regime has become a powerful countervailing force due to emergence of the AIDS crisis. Many international aid organizations use inexpensive Indian generic drugs to save money as they save lives. For example, India is a big supplier of low-price generic versions of drugs for treating AIDS. In Africa, exports by Indian companies, especially Cipla and Ranbaxy Laboratories, helped drive the annual price of antiretroviral treatment down from $15,000 per patient a decade ago to about $200 now. Though the new patent law is not as restrictive as many feared and won't dry up supply of today's generic AIDS drugs, international organizations worry that the need to pay royalties or get licenses may constrict supplies of new drugs. All generic drugs could have been removed from the market. However, all the generic drugs already approved in India can still be sold, though sellers must pay licensing fees.

Nonetheless, many of India's innovative companies have welcomed the stronger patent protections saying that these changes have made India more competitive on global scale and will trigger further investment and innovation in India. It is expected that with the stronger patent protection, more multinational corporations will tap India's relatively inexpensive engineers, scientists and computer programmers for product design, drug development and clinical testing. In fact, multinational corporations such as General Motors Corp., Microsoft Corp. and Nokia Corp. already have research facilities in India. Financial and country analysts expect the research- outsourcing industry to grow to more than $10 billion globally in the next five years.

As India opens its markets and its companies venture abroad, companies are seeking to ensure that they profit from their own innovations. The list of top applicants in 2004 shows the importance of patents in global competition. Among the top applicants are Sony Corp, Procter & Gamble Co. and DaimlerChrysler AG - all with more than 300 applications each last year. From the Indian side, the top applicants include Dr. Reddy's Laboratories Ltd. and Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd. - both have more than doubled their research-and-development spending to about 10% of revenue.

Nicholas Piramal, a generics company based in Mumbai, India, has invested millions in research and development in the last few years. India's generic drug companies, which until now made money copying best-selling foreign drugs, has now increased spending on research with an eye to launch low-cost drugs for the global market. As Dr. Swati Piramal, director for strategic alliances and communications of Nicholas Piramal says: "If an Indian company makes a drug whose development costs are under $50 million, compared with a billion-dollar-plus development costs in the West, we will be able to change the paradigm of drug discovery."

4.1 Ambiguities in the new law

The 2005 amendments to the patent law have many ambiguities that need to be addressed. To illustrate a few: under the new law, a maker of generics can apply to copy a patented drug, but only after it has been marketed for three years. The generic's maker however must pay a "reasonable" royalty. The new law does not define what can be considered to be "reasonable". This can result into unwarranted complications and needless litigation. Further, the amendments have sparked fears that with the new law, prices on patented breakthrough drugs would most likely rise to nearly the level in the United States, while prices on more commonly used drugs would most likely rise only moderately. The Indian government has said it would step in if price rises were excessive but has not said how that would be determined. In fact, the new law bars the government from over-riding any patent for at least three years - a provision not required under the TRIPS Agreement. Further, the new law states that the Controller of Patents has a series of wide-ranging discretionary powers to determine all kind of criteria like "reasonable affordability," "reasonable pricing," and "reasonable royalty."

As Subbaraman Ramkrishna, senior director for corporate affairs at Pfizer India Ltd. noted, the word "reasonable" appears 42 times in the bill, giving the impression that royalty rates would be imposed subjectively. Lastly, with the removal of Section 5 of the law, it is not clear if chemical processes continue to be defined to include biochemical, biotechnical and microbiological processes.

The patent policy of 1970 has catered to the needs of the Indian poor. Drug price in India are one of the cheapest in the world today and are affordable to the population. On an average, drugs manufactured in India are more than 100% cheaper than the same drug in U.S. The government of India has achieved the Constitutional mandate of social economic balance by setting a maximum sale price while still leaving a reasonable profit.

4.2 WTO and TRIPS impact

TRIPS attempts to strike a balance between the long term social objective of providing incentives for future inventions and creation, and the short term objective of allowing people to use existing inventions and creations.

In the area of patents, TRIPS references the key articles of the Paris Convention and requires members to comply with them. It requires both national treatment and most-favored-nation treatment. It provides that no nation may discriminate in its patent system based on field of technology, a provision extremely important to the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries whose drugs were not patentable in several member states.

For pharmaceutical patents, the flexibility has been clarified and enhanced by the 2001 Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health. The enhancement was put into practice in 2003 with a decision enabling countries that cannot make medicines themselves, to import pharmaceuticals made under compulsory license. In 2005, members agreed to make this decision a permanent amendment to the TRIPS Agreement.

A patent may be granted for a product, or a process. In the case of a product, the patent is in the end product. In the case of a process the patent does not lie in the end product but only in the process of production. The act merely awards process patents for inventions relating to food, drugs, medicines and chemical processes. The implication is that the grant of patents is limited to the process or the method of making for inventions falling within the classification mentioned above. By changing the process, the same product can be a subject of a new process patent.

WTO members have to provide patent protection for any invention, whether a product (such as a medicine) or a process (such as a method of producing the chemical ingredients for a medicine), while allowing certain exceptions.

The TRIPS Agreement is remarkable for not merely stating the rights, which Members must protect, but also defining in great detail the national civil and criminal procedures by which they are to be enforced.

4.3 Patentability of inventions

The subject matter that is patentable under the TRIPS is broadly defined. The agreement provides that "patents shall be available for any inventions, whether products or processes, in all fields of technology including pharmaceutics." Member countries must now offer patent protection to both product and process innovations, as long as they are new and non-obvious. This change generally will require less-developed countries to adopt broader definitions of what is patentable, consistent with the laws of developed countries.

India for instance did not provide product patents for pharmaceutical drugs. It only provided for process patents. The laws in India gave rise to a thriving generic drug industry wherein practically every foreign drug was reverse engineered without fear of any sanction. The pharmaceutical industry was greatly affected by this practice and reversing this trend among developing countries was top priority for the US as TRIPS negotiations were being conducted.

However developing countries rebelled against a strict imposition of this norm without having the requisite infrastructure to implement it. They sought some compromise whereby the Article 27:1 states as follows: "Subject to the provisions of paragraphs 2 and 3, patents shall be available for any inventions, whether products or processes, in all fields of technology, provided that they are new, involve an inventive step and are capable of industrial application. Subject to paragraph 4 of Article 65, paragraph 8 of Article 70 and paragraph 3 of this Article, patents shall be available and patent rights enjoyable without discrimination as to the place of invention, the field of technology and whether products are imported or locally produced".

Level of protection that the US demanded would eventually be provided but it would be granted in a phased manner.

The compromise resulted for developing and least developed countries respectively. Developing countries like India have until January 1, 2005 to fully implement the whole gamut of TRIPS provisions and least developed countries have until January 1, 2015. Developing countries got a grace period of 5 years to implement the agreement and a further period of five years to grant product patents to those areas of technology in which product patents were not granted. They had to however provide for EMR to pharmaceutical companies. This is essentially an exclusive right for marketing a drug in the member nation for five years or until a product patent is granted or rejected, whichever period is shorter. Due to this it is possible for companies that develop such inventions to file patent applications in developing countries prior to their implementing the TRIPS provisions in full. Applicants can also claim the date of filing as the priority date.

Under TRIPS, even though a patent may not be granted until the end of the grace period, the invention must be afforded patent protection for the remainder of the patent term, as measured from the filing date.

Under the TRIPS Agreement, governments can make limited exceptions to patent rights, provided certain conditions are met. For example, the exceptions must not "unreasonably" conflict with the "normal" exploitation of the patent. Members may also exclude from patentability

- iagnostic, therapeutic and surgical methods for the treatment of humans or animals;

- Plants and animals other than micro-organisms, and essentially biological processes for the production of plants or animals other than non-biological and microbiological processes. However, Members shall provide for the protection of plant varieties either by patents or by an effective sui generis system or by any combination thereof. The provisions of this subparagraph shall be reviewed four years after the date of entry into force of the WTO Agreement.

Many countries use this provision to advance science and technology. They allow researchers to use a patented invention for research, in order to understand the invention more fully. In addition, some countries allow manufacturers of generic drugs to use the patented invention to obtain marketing approval-for example from public health authorities-without the patent owner's permission and before the patent protection expire. The generic producers can then market their versions as soon as the patent expires. This provision is sometimes called the "regulatory exception" or "Bolar" provision.

This has been upheld as conforming to the TRIPS Agreement in a WTO dispute ruling. In its report adopted on 7 April 2000, a WTO dispute settlement panel said Canadian law conforms to the TRIPS Agreement in allowing manufacturers to do this. (The case was titled "Canada-Patent Protection for Pharmaceutical Products").

4.4 Compulsory Licensing

Compulsory licensing is when a government allows someone else to produce the patented product or process without the consent of the patent owner. In current public discussion, this is usually associated with pharmaceuticals, but it could also apply to patents in any field.

The agreement allows compulsory licensing as part of the agreement's overall attempt to strike a balance between promoting access to existing drugs and promoting research and development into new drugs. But the term "compulsory licensing" does not appear in the TRIPS Agreement. Instead, the phrase "other use without authorization of the right holder" appears in the title of Article 31. Compulsory licensing is only part of this since "other use" includes use by governments for their own purposes.

In the main Doha Ministerial Declaration of 14 November 2001, WTO member governments stressed that it is important to implement and interpret the TRIPS Agreement in a way that supports public health-by promoting both access to existing medicines and the creation of new medicines. They therefore adopted a separate declaration on TRIPS and Public Health. They agreed that the TRIPS Agreement does not and should not prevent members from taking measures to protect public health. They underscored countries' ability to use the flexibilities that are built into the TRIPS Agreement, including compulsory licensing and parallel importing. And they agreed to extend exemptions on pharmaceutical patent protection for least-developed countries until 2016.

Article 31(f) of the TRIPS Agreement says products made under compulsory licensing must be "predominantly for the supply of the domestic market". This applies to countries that can manufacture drugs-it limits the amount they can export when the drug is made under compulsory license. And it has an impact on countries unable to make medicines and therefore wanting to import generics. They would find it difficult to find countries that can supply them with drugs made under compulsory licensing.

The legal problem for exporting countries was resolved on 30 August 2003 when WTO members agreed on legal changes to make it easier for countries to import cheaper generics made under compulsory licensing if they are unable to manufacture the medicines themselves. When members agreed on the decision, the General Council chairperson also read out a statement setting out members shared understandings on how the decision would be interpreted and implemented. This was designed to assure governments that the decision will not be abused.

The decision actually contains three waivers:

- Exporting countries obligations under Article 31(f) are waived-any member country can export generic pharmaceutical products made under compulsory licenses to meet the needs of importing countries.

- Importing countries obligations on remuneration to the patent holder under compulsory licensing are waived to avoid double payment. Remuneration is only required on the export side.

- Exporting constraints are waived for developing and least-developed countries so that they can export within a regional trade agreement, when at least half of the members were categorized as least-developed countries at the time of the decision. That way, developing countries can make use of economies of scale.

Carefully negotiated conditions apply to pharmaceutical products imported under the system. These conditions aim to ensure that beneficiary countries can import the generics without undermining patent systems, particularly in rich countries. They include measures to prevent the medicines from being diverted to the wrong markets. And they require governments using the system to keep all other members informed each time they use the system, although WTO approval is not required. At the same time phrases such as "reasonable measures within their means" and "proportionate to their administrative capacities" are included to prevent the conditions becoming burdensome and impractical for the importing countries.

5.0 TRADE MARKS

A symbol (logo, words, shapes, a celebrity name, and jingles) used to provide a product or service with a recognizable identity to distinguish it from competing products. Trademarks protect the distinctive components which make up the marketing identity of a brand, including pharmaceuticals. They can be registered nationally or internationally, enabling the use of the symbol ®. Trade mark rights are enforced by court proceedings in which injunctions and/or damages are available. In counterfeiting cases, authorities such as Customs, the police, or consumer protection can assist. An unregistered trade mark is followed by the letters ™. This is enforced in court if a competitor uses the same or similar name to trade in the same or a similar field.

A service mark is the same as a trademark except that it identifies and distinguishes the source of a service rather than a product. The terms "trademark" and "mark" are commonly used to refer to both trademarks and servicemarks.

Trademark rights may be used to prevent others from using a confusingly similar mark, but not to prevent others from making the same goods or from selling the same goods or services under a clearly different mark. For example, in the case of pharmaceutical industry, the court considers the type of the drug and the purchaser and such other aspects before it reaches a decision. In the case of Win-Medicare Ltd V. DUA Pharmaceuticals Pvt Ltd, Diclomol was used by the plaintiff and Dicamol was used by the defendant. The court held that the two products were similar and considered the factor that these drugs are sold without prescription. Therefore these drugs can be bought off the counter by illiterate customer and therefore restrained the use of the trademark by holding that they are similar.

5.1 Some important cases

The Delhi High Court granted an ex-prate injunction to SmithKline Beecham Ltd. which was the registered owner of the mark Crocin against the use by Apar Pharma of Hyderabad and Cyper Pharma of Delhi against the use of the word Crocinex. Both the marks were sought to be used for paracetamol tablets. The Court held that the words were so similar that the attempt was to deliberately mislead the public.

On the other hand, in Cadila Lab v. Dabur Pharma Ltd, Cadila alleged that Zexate was deceptively similar to Mexate in respect of a particular injection used to treat cancer. The Court based its conclusions only on the fact that the drugs were specialized drugs which could only be purchased showing the prescription of a cancer specialist. It was felt that the prescriptions were made by specialist doctors who are knowledgeable and are capable of distinguishing the names and therefore court held that the trademarks can be allowed.

The same logic was followed in the case of Biofarma V. Sanjay Medical Store; the question was with reference to Flavedon and Trivedon for a drug that was prescribed for heart disease. The court gave importance to the fact that the drug was a Schedule H drug under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, which meant that the drug cannot be bought off the counter. The Court held that the two drugs need not be considered to be deceptively similar on the same logic followed in the above mentioned case.

In Biochem Pharmaceutical Industries V. Biochem Synergy Ltd, both companies were engaged in the business of selling pharma and medical products. Biochem Synergy was engaged in bulk drugs whereas Biochem Pharma was selling their drugs in strips of 10 which were available with the chemist and druggist. Here it was argued that the name Biochem was a combination of BIO and CHEM and therefore was not distinctive.

The court considered that the name Biochem was registered by Biochem Pharma and that there were 28 trademarks of the company beginning with that name. Biochem Pharma had also been in the business for the past 35 years, thereby acquiring a reputation. Hence the court held that Biochem Synergy desist the use of the word Biochem in order to ensure that the consumers are not unnecessarily confused and misled.

Recently in, Allergen Inc V. Milment Optho, the Supreme Court of India considered the issue of trans-border reputation. Allergen Inc was the manufacturer of eye care products under the trademarks Ocuflox, and has registered the mark in over nine countries. Allergen had applied for registration of its mark in India. It contended that Milment Optho which also manufacturers eye care products was using the same mark in India for similar goods. The Single Judge of the Calcutta High Court had issued an interim order restraining Milment from using the mark, which was vacated after hearing the Indian Company. The case went on appeal to the Supreme Court. The Court considered certain remarks that were made by the Division Bench of the Calcutta High Court where the Calcutta High Court had mentioned that these foreign brand names were no more alien to the Indians on account of the higher rate of travel and the increased advertisement in India. Eventually, Milment offered to change its name in the Supreme Court.

6.0 THE GLIVEC CASE

Novartis has lost an about 7 years long legal battle to secure a patent protection for its invention on beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate in India.

A 112 page long Supreme Court judgement delivered by a Supreme Court (SC) bench comprising Justice Aftab Alam and Justice Ranjana Prakash Desai details a complete account of all events leading to appeal to Supreme Court and a historical account of India's patent regime including policy decisions leading to amendment of section 3d in 2005, in addition to providing detailed discussion on entire facts of the case.

The whole pharmaceutical community around the world were eagerly waiting for the decision and particularly to know how the Supreme Court construes a controversial section 3d. We would discuss herein SC's discussion and decision especially on section 3d.

Events leading to appeal to the Supreme Court

- Novartis filed a patent application 1602/MAS/1998 at the Indian Patent Office.

- Five pre-grant oppositions were filed by various Indian generic companies and the Cancer Patient Aid Association (CPAA).

- The Application was rejected by the Controller in 2006 after hearing 5 pre-grant oppositions.

- Novartis filed an appeal to Madras High Court. The appeal was eventually transferred to the Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB) after its formation. Novartis also filed writ petitions challenging section 3d of the Indian Patent Act which were dismissed by the High Court after which no further action was taken by Novartis.

- IPAB upheld the Controller's decision in 2009.

- Novartis filed an appeal in the Supreme Court later in 2009.

6.1 The controversial section 3(d)

This case mainly revolves around whether the beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate is hit by section 3d and thus unpatentable in India. There was a detailed discussion in the judgement on how section 3d is introduced and amended and how section 3d is a part of patentability criteria.

So, let us first see what section does section 3d mean: Section 3d bars patent protection to new forms (including salts, esters, polymorphs, crystalline forms, derivatives etc.) of known substances unless the new forms result in an enhancement of the known efficacy.

Supreme Court held that in this case, "known substance" is imatinib mesylate and not imatinib in free base. SC held that that the prior art patent US Patent No. 5,521,184 (Zimmermann patent) claiming imatinib, also discloses imatinib mesylate and the known substance with which the beta crystalline form must be compared to show enhanced efficacy thus should be imatinib mesylate and not imatinib in free base form.

Novartis in its arguments had compared beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate with imatinib in free base form to prove enhanced efficacy (Novartis showed 30% enhanced bioavailability in beta crystalline form over imatinib in free base plus other physico-chemical properties as discussed hereinafter).

Evidence that proved that imatinib mesylate is disclosed in Zimmermann patent: Zimmermann patent discloses imatinib in free base form and further discloses a broad coverage of pharmaceutical acceptable salts (including acid addition salts) generally where explicit disclosure of mesylate salt is not there. The patent is granted in 1998.

Novartis filed a new US patent on beta crystalline form of imatinib mesylate. The patent is granted in 2005. NDA (New Drug Application) for Glivec or Gleevec was filed in 2001, where the active ingredient of the drug was stated as Imatinib mesylate. Active ingredient, composition and method of use were also declared by Novartis to be covered by the Zimmermann patent.

Further, when Novartis sent a legal notice in 2004 to Natco, the company selling generic version of Glivec in UK, Novartis stated in the notice that the Zimmermann patent (EP equivalent) claims imatinib and its acid addition salts such as the mesylate salt.

The judges concluded based on the above evidence that imatinib mesylate is disclosed in Zimmermann patent and thus is a known substance with which beta crystalline form must be compared to show enhanced efficacy over the known substance.

Supreme Court held that "efficacy" in case of chemical substances, especially medicine, is "therapeutic efficacy".

Madras High Court earlier in this case held efficacy to mean therapeutic efficacy.

SC re-clarifies the meaning by saying, "Efficacy means "the ability to produce a desired or intended result"….. Therefore, in the case of a medicine that claims to cure a disease, the test of efficacy can only be "therapeutic efficacy"……..What is evident, therefore, is that not all advantageous or beneficial properties are relevant, but only such properties that directly relate to efficacy, which in case of medicine, as seen above, is its therapeutic efficacy."

Novartis tried to prove enhanced efficacy by showing better physico-chemical properties (such as better flow properties, better thermodynamic stability, lower hygroscopicity etc.) over imatinib in free base form. However SC held that these properties can give better processability, storability, stability etc. but cannot be said to possess enhanced efficacy (that is therapeutic efficay) over Imatinib Mesylate under section 3d.

SC clarifies that:

"…just increased bioavailability alone may not necessarily lead to an enhancement of therapeutic efficacy. Whether or not an increase in bioavailability leads to an enhancement of therapeutic efficacy in any given case must be specifically claimed and established by research data."

It was held that no evidence was provided by Novartis to prove that the beta crystalline form of Imatinib Mesylate shows an enhanced therapeutic efficacy (on molecular basis) over Imatinib free base in in vivo animal model.

SC thus finally concluded and held that the beta crystalline form of Imatinib Mesylate fails the test of section 3(d) and thus is unpatentable.

7.0 DRUG PRICES CONTROL ORDER (DPCO) & NPPA

The National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority (NPPA) was formed in 1997 as a government regulatory body to control drug prices in India. It has the power to enforce the DPCO 2013. It monitors prices of decontrolled drugs, and also recovers amounts overcharged by manufacturers. Those issues, although, often land up in courts.

With the objective to improvise and endow with the basic health care and availability of basic medicines at an affordable price across the country, the Department of Pharmaceuticals, Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers, notified the Drug (Prices Control) Order 2013 ("DPCO 2013") in May 2013, which may fluctuate the pricing of 348 essential medicines. Prior to the 2013 regime, the DPCO 1995 included 74 bulk medicines within its ambit and the pricing of the drugs were fixed on the basis of manufacturing costs declared by the drug manufacturers (i.e. makers of active pharmaceutical ingredients or bulk drugs or formulations).

The National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority (NPPA) has been given the powers to enforce the Drug Prices Control Order (DPCO). It also advises the Government of India in matters of drug pricing and policy. It also has the mandate to control prices of drugs listed in the National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM). In July 2014, price control was extended to drugs outside NLEM and 108 drugs relating to cardiac diseases and diabetes were bought under the price control mechanism. Several industry bodies, including Indian Pharma Alliance (IPA), criticised the NPPA's move and in the end of July, the IPA challenged the NPPA notification in Bombay High Court. After consulting legal experts, the Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers, under which the NPPA functions, told the Court that it would withdraw the guidelines it issued for bringing 108 cardiac and diabetes drugs. In September 2014, the controversial order which extended price control to 108 drugs was withdrawn.

The rationale that is being used for decontrolling the drug prices is that market forces are best suited to stabilise drug prices, and that the industry must be made more profitable in order for it to increase investment on R&D and be globally competitive. However the immediate effect of the decontrol of drug prices has been a spurt in the prices of these drugs. The Pharma firms benefitted as a certain percentage of their sales would be outside the price control regime. Also, there was a spurt in the prices of shares of the pharma companies in the wake of this order.

As said earlier, the DPCO 2013 empowered the NPPA to regulate prices of 348 essential drugs. As per the new DPCO 2013, all strengths and dosages specified in the National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM) will be under price control. We will now provide an insight of the key aspects of the DPCO 2013 and discuss the manner in which such provisions have been implemented. Para 2(i) of the DPCO 2013 defines the term "Formulation" as a medicine processed out of or containing one or more drugs with or without use of any pharmaceutical aids, for internal or external use for or in the diagnosis, treatment, mitigation or prevention of disease and, but shall not include -

- any medicine included in any bonafide Ayurvedic (including Sidha) or Unani (Tibb) systems of medicines;

- any medicine included in the Homeopathic system of medicine; and

- any substance to which the provisions of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940 (23 of 1940) do not apply;

As per the DPCO 2013, "Scheduled formulation" means any formulation, included in the First Schedule whether referred to by generic versions or brand name. "Nonscheduled formulation" has been defined as a formulation, the dosage and strengths of which are not specified in the First Schedule.

"Schedule" is the Schedule appended to the DPCO 2013.

PRICING OF SCHEDULED FORMULATION: Para 4 of the DPCO 2013 provides formula for the calculation of ceiling price of a scheduled formulation as follows -

Step 1. First the Average Price to Retailer of the scheduled formulation i.e. P(s) shall be calculated as below:

AVERAGE PRICE TO RETAILER, P(S) = (Sum of prices to retailer of all the brands and generic versions of the medicine having market share more than or equal to one percent of the total market turnover on the basis of moving annual turnover of that medicine) / (Total number of such brands and generic versions of the medicine having market share more than or equal to one percent of total market turnover on the basis of moving annual turnover for that medicine.)

Step2. Thereafter, the ceiling price of the scheduled formulation i.e. P(c) shall be calculated as below:

P(c) = P(s) × (1+M/100), where P(s) = Average Price to Retailer for the same strength and dosage of the medicine as calculated in step1 above. M = % Margin to retailer and its value =16

Calculation of Ceiling Prices of following has also been provided in the DPCO 2013.

- Ceiling price of a scheduled formulation in case of no reduction in price due to absence of competition

- Calculation of Retail price of a new drug for existing manufacturers of scheduled formulations.

PRICING OF NON-SCHEDULED FORMULATIONS: Apart from the price fixation of the Scheduled Formulations, the NPPA is also empowered to monitor the maximum retail prices (MRP) of all the drugs, including the non-scheduled formulations and ensure that no manufacturer increases the maximum retail price of a drug more than ten percent of maximum retail price during preceding twelve months and where the increase is beyond ten percent of maximum retail price, it is empowered to reduce the same to the level of ten percent of maximum retail price for next 12 months. The manufacturer shall be liable to deposit the overcharged amount along with interest thereon from the date of increase in price in addition to the penalty.

DISPLAY OF PRICES OF SCHEDULED & NONSCHEDULED FORMULATIONS AND PRICE LIST: Para 24 and 25 of the DPCO 2013 mandate that every manufacturer of a Scheduled & non-Scheduled formulation intended for sale shall display in indelible print mark, on the label of container of the formulation and the minimum pack thereof offered for retail sale, the maximum retail price of that formulation with the words "Maximum Retail Price" preceding it and the words 'inclusive of all taxes' succeeding it. Para 26 lays down that no person shall sell any formulation to any consumer at a price exceeding the price specified in the current price list or price indicated on the label of the container or pack thereof, whichever is less.

RECOVERY OF OVERCHARGED AMOUNT UNDER DPCO 1987 AND 1995: Para 23 states that notwithstanding anything contained in the order, the Government shall by notice, require the manufacturers, importer or distributor or as the case may be, to deposit the amount accrued due to charging of prices higher than those fixed or notified by the Government under the provisions of Drugs (Prices Control) Order, 1987 and Drugs (Prices Control) Order, 1995 under the provisions of this Order.

MARGIN TO RETAILER & MAXIMUM RETAIL PRICE: Para 7 lays down that while fixing a ceiling price of scheduled formulations and retail prices of new drugs, sixteen percent of price to retailer as a margin to retailer shall be allowed. Para 8 specifies that the maximum retail price of scheduled formulations shall be fixed by the manufacturers on the basis of ceiling price notified by the Government plus local taxes wherever applicable. Even the loose quantities of any formulation shall not be sold at a price which is in excess of pro-rata price of the formulation.

Updates in 2016: The National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM) list 2011 has been changed to NLEM 2015. Under NLEM 2011, 348 drugs were included. NLEM 2015 has 376 drugs. Overall, now 800 plus drug formulations are under price control. Today, nearly 1400 cases are under litigation where NPPA has issued penalty notices to pharma companies (more than $670 million). Hence, overall, in 2016, around 18% of Indian Pharma market is now under price control. The government also launched the “Pharma Jan Samadhan” scheme in March 2015. It has a web-based complaints redressal system regarding pricing and availability of medicines. The task of the government is to balance industry-needs with socio-economic necessities.

8.0 No proposal to change Indian Patent Act

In February 2015, India ruled out any amendment(s) to the patent law, asserting that there are no gaps in protection of Intellectual Property Rights (IPR). While replying to questions in the Rajya Sabha, Commerce and Industry Minister Nirmala Sitharaman said that the government is under “no pressure” on the IPR front from any quarter and Indian laws meet international norms. On protection of Indian traditional knowledge, the Minister said the government is seized of the matter and all aspects are being taken care of. Congress leader and former Commerce Minister Anand Sharma expressed concern that the US has a strong lobby putting pressure on India to go beyond TRIPS in the pharmaceutical sector. To this, Sitharaman said no new joint task force has been set up with the US to deal with IPR issues. She said under the India-US Trade Policy Forum, the government was continuing the mechanism put in place in 2010. There are five committees, including one on IPR. The Minister said a think tank has been set-up to come out with a broad policy on IPR. The think tank has already submitted its first draft report on which the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP) has sought public comments.

9.0 INDIAN PATENTS ACT

The Indian Patents Act 1970 was implemented by the government of India in 1972. It made pharmaceutical product innovations, as well as those for food and agro-chemicals, un-patentable in India. It allowed innovations patented elsewhere freely copied and marketed in India. Further, this Act restricted import of finished-formula, imposed high tariff rates and introduced strict price control regulation. This Act was not beneficial to the big foreign multinational organizations and was not in sync with the global patent system.

In order to ensure compliance with the IPR regime under WTO, the 1970 Act was required to be amended. The requirements were that a Mailbox System be set up and Exclusive Marketing Rights (EMR) be allowed. Under the EMR, an international company would get exclusive rights to market a product in the field of pharmaceuticals and agricultural chemical products in the Indian market for a specified period (5 years). The Mailbox System is a ‘box’ which received all applications for the patenting of pharmaceutical and agricultural chemical products. These provisions were included in the Patents Act through 1999, 2001 and 2002 amendments. The applications in the mail box were considered in 2005.

These amendments though far reaching, still did not bring the Indian Patents Act in full conformity with the global intellectual property system. This conformity was introduced through the Patents Amendment Act 2005. The main provisions of this Amendment Act were:

Product Patent: The Act extends product patent protection in all fields of technology, i.e. drugs, food and chemicals. Earlier only process patent was allowed which limited patent rights. For example, a process patent was awarded to the way a cure for, say cancer, is manufactured and not for the cure. This allowed the other manufacturers to produce the same cure by some other method and hence not violate patent rights of the original manufacturer. But now after the 2005 Amendment, patent is awarded to the way cancer cure is manufactured and to the cure as well.

Compulsory Licensing: This is a TRIPS compliant provision empowering the governments to check and control the misuse of patents. Inspite of the existence of a patent, the govt can invoke the compulsory license to make available the patented product to the people in case of national emergency for public non-commercial use. The govt can also invoke compulsory licensing if it feels that the public requirements with regard to a patented product have not been met and the product is not available for the public at an affordable price.

Embedded Software: The Act allows for patenting of embedded software.

Other provisions: The Act allows the patent holder to challenge the license so that he can block general production of his drug. Pre-grant and post-grant opposition clause has been provided. The Act also removes provisions relating to EMRs besides strengthening the provisions relating to national security to guard against patenting abroad of dual use technologies.

According to the Patents Act 2005 the following items are not patentable:

- A frivolous invention or one that claims anything contrary to established natural laws.

- An invention the use of which would be contrary to morality or injurious to public health.

- The mere discovery of a scientific principle or the formulation of an abstract theory.

- The mere discovery of any new property or new use of a known substance or the mere use of a known process, machine or apparatus unless such known substance results in a new product or employs atleast one new reactant.

- A substance obtained by a mere admixture resulting only in the aggregate properties of the components thereof or a process for producing such substance.

- The mere arrangement or rearrangement or duplication of known devices functioning independently of one another in a known way.

- A method or process of testing applicable during the process of manufacture rendering the machine, apparatus or other equipment more efficient, or for the improvement or restoration of the existing machine, apparatus or other equipment for the improvement or control of manufacture.

- A method of agriculture or horticulture

- Inventions relating to atomic energy

9.1 The US Concerns

The US government has retained India on the 'Priority Watch List' of nations in the U.S. Trade Representative's 'Special 301 'annual report on global intellectual property rights (IPR) regimes, on the basis that there were "growing concerns with respect to the environment for IPR protection and enforcement in India."

According to the United States, "serious questions" regarding the future of the innovation climate in India across multiple sectors. The United States Trade Representative (USTR's) closely-watched report urged India to address concerns such as online piracy and 'camcording incidents' affecting the film industry, to promote predictability in patent laws including the question of section 3(d) of India's Patent Act and tackle concerns stemming from Section 84 of the Act and the Intellectual Property Appellate Board's support for the grant of compulsory licenses.

According to the USTR report, there are significant delays in India's Institutional infrastructure in proceedings before the Trademark Registry. Moreover there are difficulties in obtaining remedies and damages for trade secret violations. The report also mentions about discriminatory actions and policies that favour local manufacturers in a way that distorts the competitive landscape.

Analysts in India however say that the report is a unilateral measure to pressurise countries to accept IPR protections beyond WTO obligations. During Obama's visit to India in January 2015 this issue had cropped up but no solution had been found.

10.0 Recent major issues relating to drug patenting and pricing

10.1 Government of India criticized for decision to allow U.S.- trained patent examiners

Humanitarian aid organisation Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) has questioned the Indian government’s decision to have patent officers trained by the United States Patent & Trademark Office after the recent controversy over compulsory licensing. The government gave private, verbal assurance to U.S. industry lobby groups — the U.S. India Business Council (USIBC) and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce — that it would not use ‘compulsory licensing’ for commercial purposes, indicating that the Indian patent office won’t readily give out patents to domestic pharma companies for low cost generic versions of patented drugs.

Rights-based access campaigners say that the USIBC, which receives funding from multinational pharmaceutical companies, has been conducting training sessions for Indian patent examiners. The fear is that it is likely to orient them to the narrative of Big Pharma.

The USIBC training module, a patent examiner in the Mumbai patent office said, was helping Indian examiners assess applications of life saving pharmaceutical products. Training is given by senior examiners from US PTO. Duration is from 3-6 days to six months. Officers have also been sent from India to the U.S. for training. Indian examiners usually learn as much as they can from the U.S. but try not to compromise our policy on Section 3(d). There seems to be a clash of interest but these decisions are taken at a policy level. However, activists fear that this allows the U.S. pharmaceutical industry, which wants a more favourable patent regime, to influence India’s patent office decisions. The MSF maintains that this is a part of the U.S. policy to single out India — the world’s principal producer and supplier of quality generic medicines — for lax enforcement of intellectual property.

The most striking allegation is that since the Indian FDA has independent regulatory pathways to register low cost generic versions of new drugs, millions of people are living with HIV receiving treatment supplied by Indian manufacturers. Hence the U.S. pharmaceutical industry, backed by the USTR, wants Indian authorities to relax their patent examination system and is now even training patent examiners through business associations.

10.2 Eli Lilly – the US pharma giant – wants a favourable patent regime in India

Eli Lilly wants a more favourable patent regime in India that “rewards innovation” and would welcome an open dialogue from the government in this respect. Its logic is that it is an innovation-driven company, and takes years to develop a medication at a huge cost. It is very important to have an environment that really rewards innovation.

Now, Eli Lilly’s push for a favourable patent regime comes at a time when a lobby of US drug makers has termed the intellectual property (IP) environment in India as “weak”. In its annual Special 301 Report that reviews the state of IPR (intellectual property rights) protection among the US’s trading partners, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) said India’s legal and regulatory systems pose procedural and substantive barriers at every step of the patents process. PhRMA, a body representing leading pharma and biotech companies in the US, has added the country to its priority watch list.

10.3 Pharma company Viiv’s attempt to secure patents for key HIV drugs dolutegravir and cabotegravir opposed in India

‘Patent opposition’ by patients seeks to ensure availability of affordable generics.

People living with HIV have opposed patent applications in India for two important HIV medicines, dolutegravir and cabotegravir. Médecins Sans Frontières/ Doctors Without Borders (MSF) supports these ‘patent oppositions,’ which have been filed to challenge an attempt by ViiV Healthcare (a joint venture by Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline) to obtain monopoly rights in India while several of its patent claims are questionable according to Indian patentability criteria.

The company has so far failed to make dolutegravir available in India for people who have run out of other treatment options. Cabotegravir is still in the clinical trial phase of development.

Patients suffering from HIV say that many of them have now developed resistance to existing medicines and are in dire need of new drugs to stay alive. Affordable generic medicines from India have been one of the cornerstones for being able to put nearly 16 million people on HIV treatment in developing countries.

Dolutegravir has been available for use in the US and Europe for more than two years, and is now part of first-line HIV treatment in the US as it reduces virus levels faster, is very well tolerated and has a high barrier to resistance. In developing countries, it is urgently needed for some patients who have developed resistance to available first- and second-line medicines. However, the drug is not available from ViiV in India as the company has neither applied for registration in the country, nor makes the drug available under ‘compassionate use’ programmes for dying patients in India. ViiV licensed dolutegravir to several Indian generic companies in 2014 under a voluntary licence signed between ViiV and the Medicines Patent Pool, as well as at least one bilateral licence outside of the Medicines Patent Pool. Yet, ViiV has effectively blocked access to the drug through licence conditions that limit its supply to public sector entities and NGOs in India with prior permission from the company – and not through private sales. If ViiV now gets a patent for dolutegravir in India, open generic competition among Indian producers would be blocked, keeping the drug out of reach of patients who desperately need immediate access.

People with HIV in India have had to deal with long delays and it has taken years for new HIV drugs and monitoring tools to be introduced in the treatment programme by the National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO). The irony is that the drug will be produced in India and exported to Africa, but won’t be available to Indian patients who need it.

The second drug, cabotegravir, with a similar structure as dolutegravir, is still under development by ViiV. Clinical trials are on-going to evaluate this compound, which is being developed as an oral tablet but also as a long-acting injectable formulation, which could make new treatment options available for people living with HIV.

The allegation is that patents for these drugs would mean complete monopoly status for a company which has already restricted the availability of an important HIV drug in India. MSF relies on affordable medicines made in India to treat more than 200,000 people around the world living with HIV, and uses Indian generic medicines to treat many other diseases and conditions, such as malaria and tuberculosis. The only way people living with HIV in India and across the developing world will be able to access these new life saving HIV medicines is if unrestricted competition among generic producers can take place.

Background: DTG, an integrase inhibitor, has been found to have a high barrier to development of drug resistance. For HIV+ patients who have failed treatment with most other anti-retrovirals and now require a third line regimen, treatment with a DTG-containing regimen is useful since it has higher barrier to resistance than other options like raltegravir, which can develop resistance quickly. DTG is now recommended as an alternative first line drug in the revised WHO guidelines for HIV treatment as it is a well-tolerated once-daily ARV that reduces virus levels faster, has a high barrier to resistance and has few drug interactions. The patent application in question (3865/KOLNP/2007) filed jointly by the pharmaceutical companies, GSK and Shionogi is at a critical stage of examination before the Kolkata Patent Office. ViiV Healthcare acquired exclusive global rights to several integrase inhibitor compounds, including dolutegravir from a Japanese pharmaceutical company, Shionogi & Co. Ltd. Shionogi receives ongoing royalties and has 10% equity in ViiV Healthcare. ViiV Healthcare is a company established in November 2009 by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Pfizer. ViiV Healthcare, under a license to the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP), has placed India on a list of royalty countries where the drug can be supplied by generic companies (sub-licensees) but only to Indian public sector entities and NGOs, with the prior approval from the company. Generic companies like Aurobindo are now manufacturing the drug in India, but only for export to other countries as it is not yet registered in India. In 2013, the Delhi Network of Positive People (DNP+) filed the first opposition against the grant of the application that claimed a vast number of integrase inhibitor compounds – an important class of HIV medicines. A markush claim is a common form of ever-greening by companies that claim millions of compounds in a single patent application without disclosing which exact medicine they are planning to put into development and production. (More on Markush Claim here - http://www.bitlaw.com/source/mpep/803_02.html )

10.4 A leukemia pill that costs $9,000 in US sells for $70 in India

India’s generic industry has been producing many such life-saving medicines at a fraction of the global price. The Hyderabad-based Bharat Biotech might be the first to come out with a vaccine for the Zika virus if its efficacy can be proved. If it does succeed, this won’t be the first time India has come to the rescue of the world. Indeed, the country’s generic medicines are a lifeline for millions not only in low and middle-income countries but also in the developed world. India’s generic industry hit global headlines in 2001 when Cipla offered a three-drug cocktail for AIDS at less than a dollar a day, a fraction of the price charged by multinationals. Today, apart from several HIVAIDS drugs, the industry is producing affordable, high quality medicines for several diseases including hepatitis B and C, cancers, drug-resistant TB and asthma. This has been credited to India’s patent law, often held up as a model one in preventing the abuse of patent monopolies, and in balancing public interest and the growth of the pharmaceutical industry.

In January 2016, generic manufacturer Natco announced that it would be supplying daclatasvir, a Hepatitis C drug, to 112 developing countries. In 2013, a medicine to treat hepatitis C, sofosbuvir, hit international headlines for its price -$1,000 per pill. Gram for gram, it cost 67 times the price of gold. The sofosbuivir and daclatasvir combination used for the disease costs almost $150,000 per patient for the 12-week regimen in the US. But in India, it is priced at just $700 or a little over Rs 46,500 per patient for the same regimen. And prices are expected to fall further. Typically, the price of many expensive patented drugs in European countries like France, Spain or the UK is half of what these cost in the US. In countries like Brazil or South Africa, these are a third or a fifth of the US price. The Indian price is often 1100th.

So how does the Indian generic industry manage to do it? The patent law in India is stringent on what is innovative enough to get a patent. Plus, the crucial section 3(d) in the law, much criticized by multinationals, has prevented “evergreening” -the attempt to patent different aspects and improvements of the same drug to extend the period of patent -a lucrative game for the pharmaceutical business.

Indian courts, too, have played a role. In the case of entecavir for hepatitis B and erlotinib for lung cancer, for instance, instead of blindly handing out injunctions or upholding the validity of patents, the courts ruled in favour of public access to a lifesaving drug. This encouraged companies like Cipla, Ranbaxy and Natco to do a ‘launch at risk’, a term that describes a company deciding to challenge a patent by launching a generic version. This forces the patent-holding company to take them to court, thus testing the validity of the patent granted. Patent oppositions filed by patient groups also spurred the rejection of several frivolous patent claims on cancer, hepatitis and HIV medicines, protecting generic competition.

India’s patent law also provides for granting of compulsory licences - under which the government can give a licence to a manufacturer other than the patent holder for a royalty fixed by it -for public health reasons. This can be used where drugs are unavailable or unaffordable. The only compulsory licence granted was in 2012 when the patent office allowed the Indian generic company Natco to market sorafenib, a drug patented by Bayer to treat kidney and liver cancer. This move, upheld by the Supreme Court in December 2014 helped bring down the price by 97%, unimaginable through a price negotiation with the company.

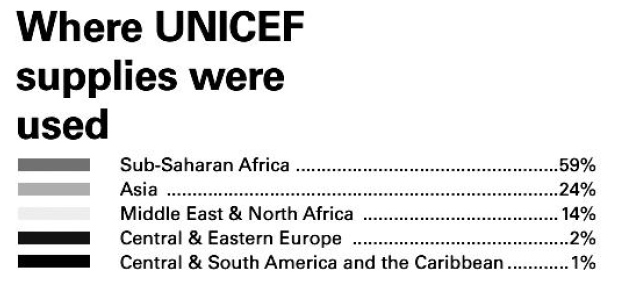

About half the essential medicines that Unicef distributes and 75% of those distributed by the International Dispensary Association, which procures medicines for 130 countries, come from India. So do about 80% of HIV AIDS medicines for the developing world.

But there is immense pressure on India from Europe, the US and their multinational pharma companies to ‘strengthen patent enforcement’. This could mean that the newer cancer and TB drugs getting patented would be out of reach for millions in India and the developing world with no generic versions to force prices down.

For example, lapatinib for breast cancer and other solid tumours, which costs over Rs 46,000 a month, or dasatanib for a kind of blood cancer, which costs over Rs 70,000 a month, have no cheaper generic versions. Even drugs like delaminid, meant for drugresistant TB, will not be available in India and the developing world despite India having the highest burden of the disease. This is because the Japanese company that holds the patent has not made it available in India. In the pre-2005 patent regime, if a company did not bring the drug to India, generic companies could step in to register it in India and start supply, but not anymore.

India is just 1-2% of the global pharma market. Yet there is intense focus on its patent law. This is “to protect the markets of large pharmaceuticals companies against competition from cheaper generic drugs manufactured in countries like India and Brazil”, explained Dr Amit Sengupta of the People’s Health Movement in an article on India’s patent law.

10.5 India and the side-effects of Pacific Treaty

The scope of the recently concluded Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPPA) goes well beyond conventional trade concerns. It includes extensive obligations on intellectual property (IP) exceeding the minimum standards of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).

Viewed against the backdrop of India’s disappointment at certain outcomes of the WTO talks in Nairobi (December 2015), countries like India will need to examine TPPA implications especially on non-violation complaints. Particularly as developed countries like the US can take developing countries like India to the WTO dispute settlement body for using TRIPS flexibilities contained in Section 3 (d) of Indian Patent Act. A number of flexibilities are not part of the TPPA.

Instead, the TPPA has adopted several TRIPS–plus provisions which effectively extend monopoly rights. Although India is not a party to the TPPA, these TRIPS-plus provisions are significant for the Indian pharmaceutical industry as they will be applied to its exports to TPPA members. This could impact and delay the entry of generic drugs, threatening access to medicines for all.

Some worrisome IP-plus features in the TPPA include patent criteria and term extension. TPPA aims to grant patents for inventions which are merely variations and not entirely new or novel. This dilutes patentability requirements leading to their “ever-greening” and extension of monopoly by at least five years. This will delay entry of a generic version of a medicine, impacting its affordability and access. Further, it provides for extension in patent term for ‘unreasonable’ delay in processing applications, which is a TRIPS-plus standard enabling the rights holder to delay launch of the product in relatively low-priced markets, particularly developing countries, again hampering access to new medicine.

Third parties are not permitted to market the same or similar products using the same or other data regarding its safety and efficacy. Even if the parties accept applications for generic medicines within those five years, marketing approval can be provided after the five-year period.

Patent linkages are the other concern for developing countries like India as this could extend the period of additional monopoly in other markets that do not have a formal system, similar to the Orange Book in the US (that binds the drug regulator to approve a generic product within the stipulated time frame), thus delaying the introduction of generics. The list of concerns do not end there. There is, for instance, the restriction on the government’s ability to utilise a compulsory licence as a means to negotiate price with the patent holder as was done by Brazil for antiretroviral medicines; and allowing private rights-holders to review and arbitrate the meaning of the WTO TRIPS Agreement.

Inclusion of path-breaking provisions such as covering IP as an asset in the investment chapter and giving customs officials powers to impound legitimate generic medicines, including for goods-in-transit, will further limit the reach of generic companies to many markets. TPPA grants additional monopoly of at least ten years to innovators through provisions that go beyond the TRIPS Agreement. This could impact society by disincentivising innovators to carry out research and development on new drugs, and force patients to pay more for ten more years.

11.0 DRAFT NATIONAL IPR POLICY

The IPR Think Tank set up by the Government of India had submitted its first Draft of the National IPR Policy on 19th December, 2014. The objectives of this Draft IPR policy are

- To create public awareness about the economic, social and cultural benefits of IP among all sections of society for accelerating development, promoting entrepreneurship, enhancing employment and increasing competitiveness.

- To stimulate the creation and growth of intellectual property through measures that encourage IP generation.

- To have strong and effective laws with regard to IP rights that are consistent with national priorities and international obligations and which balance the interests of rights owners with public interest.

- To modernize and strengthen IP administration for efficient, expeditious and cost effective grant and management of IP rights and user oriented services.

- To augment commercialization of IP rights; valuation, licensing and technology transfer.

- To strengthen the enforcement and adjudicatory mechanisms for combating IP violations, piracy and counterfeiting; to facilitate effective and speedy adjudication of IP disputes; to promote awareness and respect for IP rights among all sections of society.

- To strengthen and expand human resources, institutions and capacities for teaching, training, research and skill building in IP areas.