Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - begin learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

Spread of left-wing extremism in India

1.0 INTRODUCTION

Of the variety of extremist movements India has witnessed after 1947, the Naxalite movement has been a tough and persistent one post 1960s. Its origins can be traced back to the formation of the CPI (ML) in the 1960s and the Naxalbari uprising after which Naxalites started operating from various parts of the country. However, Naxalism emerged as a real security threat when armed groups like the Peoples' War Group and the Maoist Communist Centre joined hands in 2004 and formed the Communist Party of India (Maoists) - CPI (M) - to fight against the Indian state. In fact, one of the basic objectives of the Naxal movement is the overthrow of the state in India. Naxals do not believe in parliamentary democracy and in fact consider parliament useless. While projecting the state as well as its armed forces as the 'enemy', the Naxal movement calls upon its members to take up arms and defeat the enemy decisively. The movement believes that the State is merely an agent of the elitist class and does not really cater to the interests of the lower stratas of society.

2.0 NAXALBARI

The roots of left wing extremism in India lie in the leftist/communist political movements, labour and agrarian unrests, the revolutionary societies and the tribal revolts that erupted during various phases of colonial rule in India. Though these movements failed to reach their stated objectives, the revolutionary fervour they had instilled among the deprived sections and the mass mobilisation they were able to achieve was carried over to the post-independence period. These movements revealed that even resourceless and illiterate people can be organised and turned into a formidable force.

The independence of India from the clutches of foreign rule raised immense hopes among the landless, tribals and other downtrodden sections within the country. It didn't take too long for some sections of the masses to realise that independence had perhaps brought nothing new for them and almost everything had remained the same. Many also felt that there was no hope of change in the future. Electoral politics was dominated by the land owners and the land reforms that were promised were not being taken up in the expected spirit. The old exploitative structure had continued in a different garb. This led to a lot of disillusionment and frustration among the masses. They could recollect the prophesies of the early leftist leaders and revolutionaries that the political independence of India from British rule would in effect mean a change of exploiters and the socio-economic structure would remain the same and that an armed revolution will be needed to end the exploitation.

The radicals within the Communist Party of India in Bengal accused the party leadership of being "revisionists" as they opted for parliamentary democracy. The growing dissensions within the party ultimately led to the split of the CPI. The newly formed party, i.e. Communist Party of India (M) also participated in the United Front governments in Bengal and Kerala in 1967. But nothing substantial was realised on the ground.

The Naxalbari incident could be seen as the trigger that launched the transformation of a primarily political and socio-economic agrarian movement into an armed struggle. The incident was a fall-out of the underground efforts undertaken by the radical hardline Communist leaders like Charu Majumdar, Jangal Santhal and Kanu Sanyal who were able to motivate and mobilise the landless peasants to forcibly occupy the land belonging to the landlords whom they called "class enemies". However, some have a view that it was a result of years of ideological and tactical preparations and that the seizure of state power through an armed struggle was already on the agenda of the radical communists when this incident took place. It is worth remembering that the Soviet revolution of 1917 and Chinese communist state formation in 1949 - both by brutal force - must have acted as big motivators to the proponents of this movement in India.

In 1967, the All India Coordination Committee of Communist Revolutionaries (AICCCR) was formed to reconcile the differences within the CPI (M) party. It failed and the radical leaders were expelled from the party. They then formed a new party called Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) i.e. the CPI (ML), on April 22, 1969. Charu Majumdar was the secretary of the Central Organising Committee of the newly floated party. Radio Peking acknowledged the formation of CPI (ML) on July 2, 1969. The party was to follow the Maoist line to achieve revolution. [ Quite interesting that while the mainland China (PRC) has moved beyong Mao into a new capitalist domain, Indian Naxalites still cling to that belief. ]

The first clash was ignited when a share-cropper, Bigul Kisan, was beaten by armed agents of a local jotedar. Violent clashes followed. There was a forcible seizure of land and confiscation of food grains, by armed units of the Kisan committee. Any resistance by the landlords and their gangs was smashed and a few killed. By end May the situation reached the level of an armed peasant uprising. The CPI (M) leaders, who were now in power, first tried to pacify the leaders of the movement but they did not meet with any success. Jyoti Basu, the then home minister of West Bengal, ordered in the police. On 23rd May the peasantry retaliated killing an inspector at Jharugaon village. On May 25, in Naxalbari, the police went berserk killing nine women and children. In June the struggle intensified further, particularly in the areas of Naxalbari, Kharibari and Phansidewa. Firearms and ammunition were snatched from the jotedars by raiding their houses. People's courts were established and judgments passed. The upheaval in the villages continued till July. The tea garden workers struck work a number of times in support of the peasants. Then on July 19, a large number of para-military forces were deployed in the region. In ruthless cordon and search operations, hundreds were beaten and over one thousand arrested. Some leaders like Jangal Santhal were arrested, others like Charu Mazumdar went underground, yet others like Tribheni Kanu, Sobhan, Ali Gorkha Majhi and Tilka Majhi became ‘martyrs’. A few weeks later, Charu Mazumdar wrote "Hundreds of Naxalbaris are smoldering in India... Naxalbari has not died and will never die".

Even though the "Naxalbari uprising" was a failure, it marked the beginning of the violent LWE movement in India, and the terms "Naxalism" and "Naxalite" were born. Identification of revolutionary politics with the name of a village, and not with the name of the leader is unique in history. Thereafter, it reemerged in the early eighties, continued to gain base, and has been expanding continuously since then.

3.0 THE PEOPLE'S WAR GROUP (PWG)

The People's War Group was formed in Southern Indian State of Andhra Pradesh on April 22, 1980 by Kondapalli Seetharamaiah, one of the most influential Naxalite leaders in the State and a member of the erstwhile Central Organising Committee of the Communist Party of India - Marxist-Leninist, (CPI-ML). The PWG's operations commenced in Karimnagar district, in the North Telengana region of Andhra Pradesh, and subsequently spread to other parts of the State as well as in other States.

The PWG traces its ideology to the Chinese leader Mao Tse Tung's theory of organised peasant insurrection. It rejects parliamentary democracy and believes in capturing political power through protracted armed struggle based on guerrilla warfare. This strategy entails building up of bases in rural and remote areas and transforming them first into guerrilla zones and then as liberated zones, besides the area-wise seizure and encircling cities. The eventual objective is to install a "people's government" through the "people's war". In short, as the PWG claims, it wishes to usher in a New Democratic Revolution (NDR).

The PWG draws a clear distinction between the political and military wings of the outfit. On the political side the organisational hierarchy of the PWG consists of the Central Committee at the apex, Regional Bureaus, Zonal or State Committees, District or Division Committees and Squad Area Committees. In the military sphere, the Central Military Commission (CMC) headed by the General Secretary Ganapathi stands at the top. And there are military commissions parallel to the political committees at each level. At the bottom is the Village Defence Squad, consisting of a handful of people in a village, organised as a people's militia, and possessing basic training in handling small arms. At the political level, the Village Governance Committee is the mirror committee.

The main fighting force of the outfit is a platoon comprising 25 to 30 highly trained guerrillas organised into sections and sub-sections. There are two types of platoon - the military platoon and the protection platoon. The outfit organises its platoons as military platoons and protection platoons and fields them in the guerrilla zones. The dalam or armed squad comprising 5-7 cadres is a secondary-fighting unit. The strength of a squad is varied, as is its type. Mostly, it is in the form of a local guerrilla squad (LGS) and in some areas it functions as a central guerrilla squad (CGS).

The fighting force of the PWG is organised as the People's Guerrilla Army (PGA). It has a flag and an insignia, too. The PGA was formed in December 2000.

Estimates on the fire-power of the PWG suggest that the group has about 60 highly mobile and motivated squads of 40 persons each. In about 125 villages they run parallel administration. According to police estimate, the PWG has around 1000 to 1050 underground cadres. Besides the outfit has about 5,000 overground activists.

The PWG also has a string of front organisations of students, youth, industrial workers, miners, farm hands, women, poets, writers and cultural artists.

4.0 THE MAOIST EXPANSION

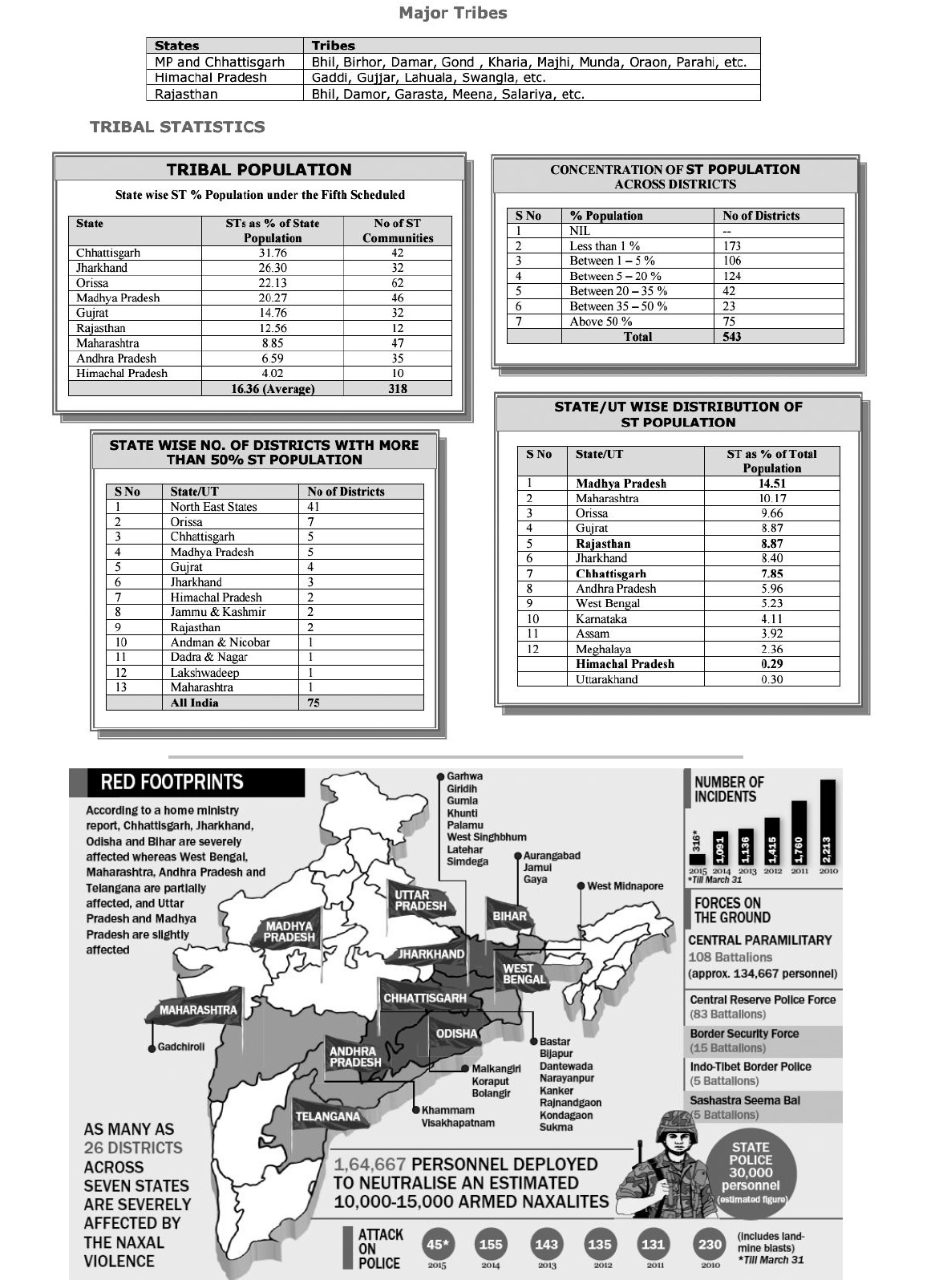

Underneath the dramatic decline in the number of Maoist related fatalities there were several 'behind the scene' developments which gave sufficient indication that the Maoists are certainly working on improving their operational strength. Due to massive deployment of security forces, it may appear that the Maoists have become weak in their traditional support bases. But the Maoist forces are making inroads into several untouched but strategically vital locations.

With the formation of its 'Upper Assam Leading Committee’ (UALC), the 'Look North East Policy' of CPI (Maoist) got a major boost. Although Assam is yet to witness a fatal Maoist strike yet there are reports of Maoist organisational activities in the 22 police stations of upper Assam districts like Tinsukia, Golaghat, Dhemaji, Dibrugarh, Sivsagar, Lakhimpur, Jorhat, and Dibang Valley. Even the Chief Minister of Assam Tarun Gogoi has requested the Prime Minister that seven districts mostly from upper Assam to be included in the list of Integrated Action Plan. (The Indian Express, 20 April 2012)

The CPI (Maoist) managed to have close fraternal ties among other groups with two vital northeastern insurgent groups namely the Revolutionary People's Front (RPF) and People's Liberation Army (PLA) of Manipur. In October 2008, the CPI (Maoist) issued a joint statement with PLA in which both reiterated their commitment to "consolidate the mutual understanding and friendship" and to "stand hand in hand to overthrow the common enemy". However, Intelligence agencies maintain that the links between the two had been firmed up in 2006. Since then, the PLA has been assisting the Maoists in procuring Chinese arms and communication equipment via Myanmar. Recently the PLA - CPI (Maoist) nexus case was revealed in a supplementary charge sheet filed by the National Investigation Agency on 21 May, 2012.

Significantly, in Manipur a faction of the Kangleipak Communist Party (KCP) has now rechristened itself as the Maoist Communist Party of Manipur. The CPI (Maoist) was working on this since quite some time but as of now the Assam-Arunachal border has emerged as another theatre of Maoist activity. Another North Eastern state, Nagaland also witnessed moderate Maoist activity during 2011 and independent sources now declare at least one district from the state as Maoist infested. Instances of Maoist links with insurgent groups such as NSCN-IM [National Socialist Council of Nagaland (Isak-Muivah)] to procure arms and ammunitions have come to the notice of the Intelligence Bureau. (Pandita, 2011)

Past few years also have witnessed the CPI (Maoist) giving a concrete shape to its long standing agenda of forming a 'Golden Corridor Committee' to connect the untouched industrial areas of Gujarat and Maharashtra. The Golden Corridor Committee stretches from Pune to Ahmedabad, to connect commercial hubs like Mumbai, Nashik, Surat and Vadodara. Besides, the Red Ultras have planned to expand their movement to Nagpur,Wardha, Bhandara and Yavatmal districts of Maharashtra. Since 2011, the CPI (Maoist) has a new thrust to its agenda of grand revival in southern states which was even admitted in the Parliament by the then Minister of State for Home Affairs Shri Jitender Singh.

Although there has been no confirmation about the presence of Malayalis in the PLGA in spite of the reports that the Maoists had raised a few squads comprising Malayalis and they had been operating in the Nilambur-Gudallur area in the Kerala-Tamil Nadu border. Reports from Intelligence sources reveal that the Maoists have been exerting particular efforts to set up bases on the tri junction of Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

With politics engulfing the Telangana region, it is now back again on the Maoist radar and the CPI (Maoist) North Telangana Special Zonal Committee (NTSZC) is now pushing hard for the revival of the naxal movement. Noticeable movement of CPI (Maoist) armed cadres in forest areas of Adilabad, Khammam, Karimnagar, and Warangal districts in the recent times have confirmed the apprehensions that Maoists have begun serious efforts to regain their foothold in areas that had witnessed intense revolutionary activity earlier.

The Maoist grand revival plan in central India got a major boost recently with the CPI (Maoist) forming the 'North Gadchiroli Gondia Balaghat Divisional Committee' comprising of strategically important areas of Gadchiroli, Gondia and Balaghat in Maharasthra and Madhya Pradesh. Gadchiroli being a Maoist stronghold, the CPI (Maoist) with the formation of a new Division under the leadership of senior Maoist leader Pahad Singh wants to implement its expansion plan in to other areas of the region.

In 2012 the Maoist prone Odisha Chhattisgarh border also witnessed the formation of Chhattisgarh-Odisha Border (COB) committee with Maoist leader Malla Raja Reddy being appointed as its first secretary. The committee has been entrusted to oversee the activities of the CPI (Maoist) in the eastern part of the Sukma-Darbha plateau in Chhattisgarh and the forest areas of Odisha along the border of the two states with the Mahasamund-Bargarh-Bolangir division being placed under its direct jurisdiction. In view of heavy deployment of security forces in the Maoist traditional bases of Chhattisgarh and Odisha the creation of COB is likely to facilitate creation of another Maoist base in the line of Abujmad.

In recent years, many states of North India have been witnessing considerable amount of Maoist activities. As per the available information the CPI (Maoist) Northern Regional Bureau (NRB) has been entrusted to oversee the revolutionary movement in Delhi, Haryana, Punjab and other areas comprising of Uttar Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand. The larger game plan of CPI (Maoist) recently became public after the arrest of senior leaders of the CPI (Maoist), including its central committee members Balraj alias B.R. alias Arvind, head of the NRB, and Banshidhar alias Chintan Da. (Frontline, 2010)

Delhi's Maoist connection has always been a matter of private discussions but the arrest of Polit Bureau member Kobad Ghandy on September 20, 2009, revealed the larger Maoist game plan for New Delhi and NCR region. As per the available information, Delhi now has a six member CPI (Maoist) committee which is managing the Maoist state of affairs in Delhi since the past 4 -5 years. Right from 2005, Maoist activities have been continuously reported from places closer to Delhi, such as Jind, Kaithal, Kurukshetra Yamunanagar, Hisar, Rohtak and Sonepat. In June 2009, Haryana police claimed to have arrested eight important Maoists in Kurukshetra, including Pradeep Kumar, the Haryana state secretary of the CPI (Maoist). The state police also claimed that the Maoists have formed a number of front organizations in the state, viz. Shivalik Jansangharsh Manch, Lai Salam, Jagrook Chhatar Morcha, Krantikari Majdoor Kisan Union, Jan Adhikari Surakhsa Samiti and Shivalik Jansangharsh Manch. (Ramanna, 2010 & 2011)

5.0 INDIAN GOVERNMENT'S APPROACH

5.1 Winning the 'Hearts and Minds' campaign

India's interior ministry, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) propagates a two-pronged approach to counter LWE - combining security force action with accelerated development of extremist affected areas. The criticism that the two-pronged approach is that it just a cover to annihilate the extremists and clear the tribal inhabited areas for exploitation by the multinational corporations and the mining companies. The extremist leader view this as an attempt to take attdention away from the governance deficit. Several ministers and officially appointed committees have underscored the need to win the 'hearts and minds' of the tribal population who constitute the primary strength and local support base of the extremists through a sustained development campaign.

The Government tried to reach out to the people of these areas through The Integrated Action Plan (IAP), launched in 2010. The objective of the plan is to develop 82 LWE affected districts. There are additional schemes for generation of rural employment, to build road infrastructures, schools, hospitals, and efforts to activate the public distribution system (PDS) with a bid to reach subsidised food items to the impoverished population. There have also been efforts to reform the land acquisition laws for new industrial units as well as mining activities in the tribal inhabited areas. Legislations have been enacted to protect the forest rights for the tribal population and initiate land reforms in various states. Implementation of each of these measures, however, remain a key challenge, affected by bureaucratic inertia, political myopia as well as challenges posed by the extremists.

Extremist violence has remained an impediment to such development efforts. The CPI-Maoist has destroyed schools, offices of local self-government institutions, roads, and mobile phones towers as part of its asymmetric warfare to deny the space and prevent the state agencies from making inroads into their stronghold areas. This, however, has not prevented the state from pouring in money into extremist-affected areas. The total annual budgetary allocation for the 82 worst affected districts for four financial years stands at Rupees 10 billion. In the battle to win the 'hearts and minds' and to meet the challenges posed by the extremists who target the developmental schemes, a 'clear, hold and develop'- strategy has been implemented with varying degrees of success. However, the proportion of money being siphoned off by the political-bureaucratic-contractor nexus in the burgeoning war economy remains substantial.

5.2 Use of force

The force-centric approach is not entirely linked to the state's inadequate gains from the developmental approach. However it has indeed contributed to the need to blunt the violence potential of the extremists as a precondition for sustainable development. The capacity of the CPI-Maoist to carry out a sustained and systematic campaign of violence targeting the security forces, police informers and civilians seen as sympathising with the state has justified the predominance of the security force operations model. Because India's successes in Punjab, Mizoram, Tripura and Andhra Pradesh have been achieved through security force operations, this model has its ardent supporters both in the official as well as strategic circles. Deploying security force battalions into the conflict affected areas has always been a convenient strategy of gaining control over the liberated zones. The development model, on the other hand, is perceived as tedious, costly and liable for disruption by extremist violence.

The myriad range of military measures employed against the CPI-Maoist include multi-theatre operations (Operation Green Hunt), localised small area operations (Operation Anaconda and Monsoon in Jharkhand and Operation Maad, Kilam, and Podku in Chhattisgarh), use of civilian vigilante groups (Sendra in Jharkhand and the disbanded Salwa Judum in Chhattisgarh), and covert intelligence operations targeting the extremist leaders. As per the Government of India (GoI) data, as on May 2013, 532 companies of the central armed police forces have been deployed in the affected states to carry out joint operations with the state police forces.

Achievements from each of these measures have been marked by setbacks. In the ensuing asymmetric warfare, security forces have lost personnel and weapons in some of the neatly executed ambushes by the CPI-Maoist. In 2010, the outfit killed an entire company of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) in Chhattisgarh's Tadmetla area. Inadequate knowledge of the terrain and lack of human intelligence (HUMINT) resulted in some of the worst incidents of civilian casualties during encounters, further contributing to the existing alienation among the tribal population. The lack of coordination between the central and the state police forces made the operations far less effective. And the worst among them all, the divergent approaches and varying intensity of counter-extremist responses across different Indian states has resulted in the inflation of insurgent balloon, allowing the Maoists to move and establish safe havens/sanctuaries in different ungoverned spaces of the country.

At the same time, each of these force-centric tactics, along with continuing efforts to modernise the state police and para-military forces, has made several tangible gains. The CPI-Maoist has lost a number of cadres to arrests, killings and surrenders, a fact claimed by the official machinery and acknowledged the outfit's published literatures. According to official data, 1707 extremists were killed between 2003 and 2012. Another 6849 were arrested and 1100 surrendered during 2010 and 2012.

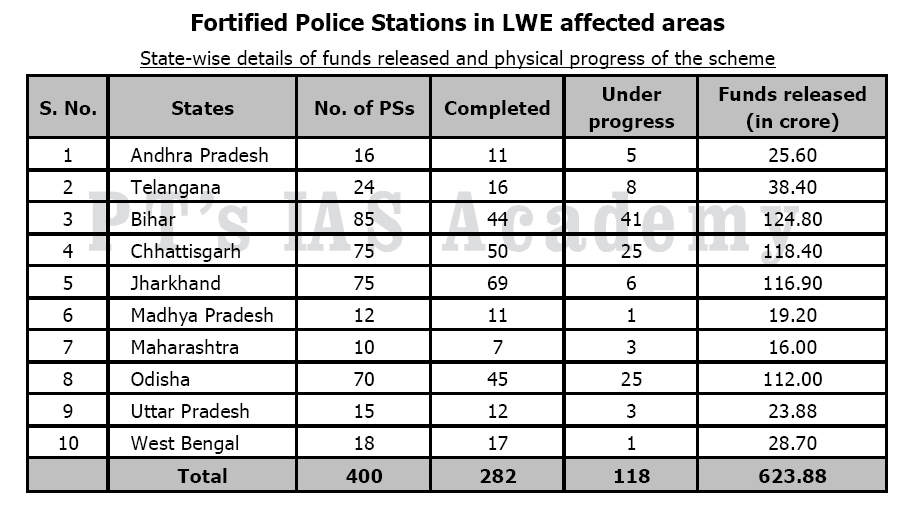

The area under the extremist domination has also shrunk after security forces cleared off some CPI-Maoist strongholds in Jharkhand, West Bengal, Odisha and Chhattisgarh. In 2011, the chief of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) claimed that his forces have managed to free about 5,000 square kilometres of area previously controlled by the Maoists. Police stations, previously the most vulnerable among the Maoist targets, turned into impenetrable fortresses after available resources were used efficiently to augment their securities, grossly undermining the 'raids for weapons'-strategy of the CPI-Maoist. The overall impact has been reflected in the extremist ability to inflict injuries and fatalities on the security forces and civilians. Fatalities among civilians and security forces declined to 301 and 114 respectively in 2012, from 720 civilians and 285 security forces in 2010. Number of violent incidents during the same period declined from 2213 to 1412.

Maoists also were affected by a range of self-generating deficiencies. Rapid expansion facilitated the entry of a large number of insufficiently motivated cadres into the organisation. Mutation along caste lines in states such as Jharkhand and Bihar initiated a phase of internecine warfare. The state agencies roped in the renegade factions and made them unofficial partners in the COIN campaign against the CPI-Maoist. Moreover, craving for media publicity also led to some senior CPI-Maoist leaders coming under the radar of the forces and consequently getting eliminated.

5.3 The Chhattisgarh attack

In the Bastar district of Chhattisgarh, the worst extremist affected state in India, the CPI-Maoist, on 25 May 2013, carried out a well planned attack targeting a convoy of vehicles carrying political leaders and activists belonging to the Indian National Congress (INC). A group of 350 Maoists consisting of men, women and children exploded improvised explosive devices (IEDs) to bring the convoy to a halt, overpowered the security forces and went about selectively killing political leaders. Among the killed were Mahendra Karma, the leader of the controversial Salwa Judum vigilante programme, and the INC's Chhattisgarh unit leader and his son. The death toll in the attack was 30 with no casualties on the Maoists side. A former union minister who was injured in the attack succumbed to his injuries on 11 June in a New Delhi hospital.

The attack carried out on the convoy did not constitute a significant military victory for the CPI-Maoist. The motley of security force personnel, mostly personal security guards protecting some of the leaders, either ran out of bullets or were overpowered by the numerically superior adversaries. Neither did the attack advance the Maoist objective of capturing state power. The attack took place in an identified extremist stronghold and did not demonstrate an audacious outreaching capacity into an area devoid of Maoist influence.

However, the violence, termed as a "frontal assault on the democratic foundations of our nation" by Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh, did pose questions on the exaggerated claims of the state about its gains vis-a-vis the extremists in the recent months. Whether optimistic official assessments regarding the on-ground situation had encouraged such bravado of the INC leaders too came under scanner. Two months before the attack, the Union Home Secretary had told a parliamentary committee, "There has been an absolute turnaround in Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand and now we are chasing the Naxal groups." A month before the attack, an internal assessment of the Intelligence Bureau (IB) had emphatically noted, "If the current momentum could be sustained for a period of few more months, it could perhaps lead to decisive tipping of scales in favour of security forces."

5.4 Rethinking COIN strategy

The 25 May violent incident in Chhattisgarh was neither the worst incident of man slaughter by the Maoists, nor did it constitute the first ever attack on politicians. However, it was for the first time that the extremists had managed to annihilate a number of prominent politicians in a single attack. The incident generated intense media attention. Predictable reactions called for swift punitive measures against the extremists. The Chhattisgarh Chief Minister categorically rejected the possibility of peace negotiations and vowed to aggressively pursue the extremists. The-then Union Home Secretary R K Singh predicted an intensification of the COIN operations (counter-insurgency). The-then Union Home Minister Sushil Kumar Shinde promised a "joint operation" of state and central forces against the Maoists.

The attack also brought about some noticeable shifts in the proclaimed perceptions of some of the key government functionaries regarding the nature of extremism. The-then Minister of Rural Development, Jairam Ramesh, a long standing advocate of the politico-developmental approach against the Maoists, termed them the attack a "holocaust"and its perpetrators, "terrorists". The-then Home Minister Shinde summed up in the shift in the following words. "So far we were thinking that this (violence) would be some other way of movement. But in 2010 incident (Tadmetla massacre in which 76 security personnel were killed) and May 25 (attack on Congress rally) we have seen it is nothing other than a terror (activity)," he said. Shinde concluded, "The (May 25) incident is bigger than terrorism". Amid the convergence of views, some dissenting voices, however, remained.

Apart from such predominantly rhetorical official assertions, the 25 May extremist attack did herald the possibility of a reset to the existing COIN strategy. The need to end the partisan differences on the issue and evolve a consensus at the national level to formulate a policy on LWE led to a meeting of different political parties on 10 June. The Prime Minister, inaugurating the meeting, underlined the need to "fine tune and strengthen" the defensive and offensive capabilities of the state against the extremists. While declining to disclose the measures initiated to "permanently root out this menace" assured the nation that his "government will not be found wanting in this regard". A resolution passed at the end of the meeting called upon the state and the central governments to "adopt a two-pronged strategy of sustained operations to clear the areas of Maoist influence and pursue the objectives of effective governance and rapid development." The parties resolved to "remain united and shall speak in one voice and act with a sense of unified purpose and will."

The content and direction of the new strategy remains matter of speculation. Some of its key parameters, however, can be inferred from the statements of bureaucrats and ministers. While an overwhelming opinion against the participation of the Indian Army against the CPI-Maoist continues to persist, the government appears prepared to abandon the policy of trying to develop the extremist affected areas, pending its sanitisation by the security forces. Underlining the difficulties of implementing development schemes in extremist controlled areas Finance Minister P Chidambaram told journalists in 2013, "In Bastar (Chhattisgarh), what development can you attempt if people can't enter?" The Home Secretary R K Singh also added that security action must precede developmental work and cannot be carried out simultaneously. A further hardening of the force-centric policy is visible through the attempt by New Delhi to coerce all states to pursue a unified national strategy against the CPI-Maoist, using preferential deployment of central police forces as a leverage tool. New Delhi intends to rapidly fill up the shortage of 27000 in the central forces' ranks to ensure an optimal force deployment in the extremist affected areas.

5.5 Lessons learnt

The new strategy appears to involve a disproportionate use of force. This represents a return to the mindset that prevailed in 2010. Operation Green Hunt (OGH) launched in the early months of 2012, involving over 70 battalions of central security forces and an equal number of state police personnel, had hoped to surmount the military challenge posed by the extremists through a rapid and decisive demonstration of strength. Within a few months, the security forces met with a series of setbacks leading to the abandonment of the operation. Lacklustre response of the civil administration failed to address the governance and development deficit (hold and develop component) both in the OGH and the subsequent focused area operations

Whether a real turnaround can be achieved through the new strategy remains unclear. It may still be possible for a determined state to neutralise some of the senior Maoist leadership and effect some fatal blows on the movement. However, unless the state demonstrates its willingness to fill up the vacuum of underdevelopment and absence of governance, Maoists in some form or the other will find an opportunity to return.

The purported objective of an extremist takeover of the country has always been an unrealistic goal. Without a comprehensive strategy and a coherent national policy that nips at the very strengths of the extremists, the government's objective of reclaiming the liberated zones too would defeated, even with the prevailing state of heightened alacrity.