Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - being learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

World War I

1.0 Introduction

With approximately 10 million soldiers dead, 22 million soldiers wounded, and 7 million civilian dead, the First World War was truly 'the Great War'. Its origins were complex. Its scale was vast. Its conduct was intense. Its impact on military operations was revolutionary. Its human and material costs were enormous. And its results were profound.

2.0 Causes of Conflict

The underlying causes of these events have been intensively researched and debated. Earlier scholars were inclined to allocate blame for the war but modern scholars are less inclined to do so. Instead they seek to understand the fears and ambitions of the governing élites of Europe who took the fateful decisions for war, particularly that of imperial Germany.

2.1 The Balkan problem

A significant cause of European tension prior to World War I was continued instability and conflict in the Balkans. The name itself referred to a large peninsula sandwiched between four seas: the Black Sea, the Mediterranean, the Adriatic and the Aegean. On this land mass was a cluster of nations and provinces, including Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria, Macedonia and Bosnia. At the turn of the century the Balkan region was less populated and under-developed, in comparison to western Europe; it had few natural resources, so was hardly an economic prize. The importance of the Balkan peninsula lay in its geographic location. Situated at the crossroads of three major empires - Ottoman, Russian and Austro-Hungarian - and with access to several important waterways, the Balkans were strategically vital. Because of this, the area had for centuries been a gateway between East and West, an area of cultural and mercantile exchange, and a melting pot of ethnicities and people.

The Balkans underwent significant change and disorder in the late 19th century. At its peak the Ottoman Empire had ruled most of eastern Europe, including the Balkan states. But by the late 1800s the Ottomans were in retreat. During this century Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria all achieved independence from Ottoman rule. Western European powers - particularly Britain, France, Germany and Russia - developed a strong interest in the region, based on concerns about what might happen once the Ottoman Empire disintegrated. They referred to this as the 'Eastern question' and developed their own foreign policy objectives. Russia hoped to expand its territory by moving into the Balkans and other areas formerly under Ottoman rule. The Russian navy, with its ports on the Black Sea, coveted access to and control of the Bosphorus, which provided shipping access to the Mediterranean. Britain was opposed to Russian expansion into the Mediterranean and the Middle East, so wanted the Ottoman Empire to remain intact for as long as feasible, to provide a buffer against the Russians. Germany hoped to acquire bankrupt Ottoman regions as vassal states, possibly even as colonies.

2.2 The Alliances

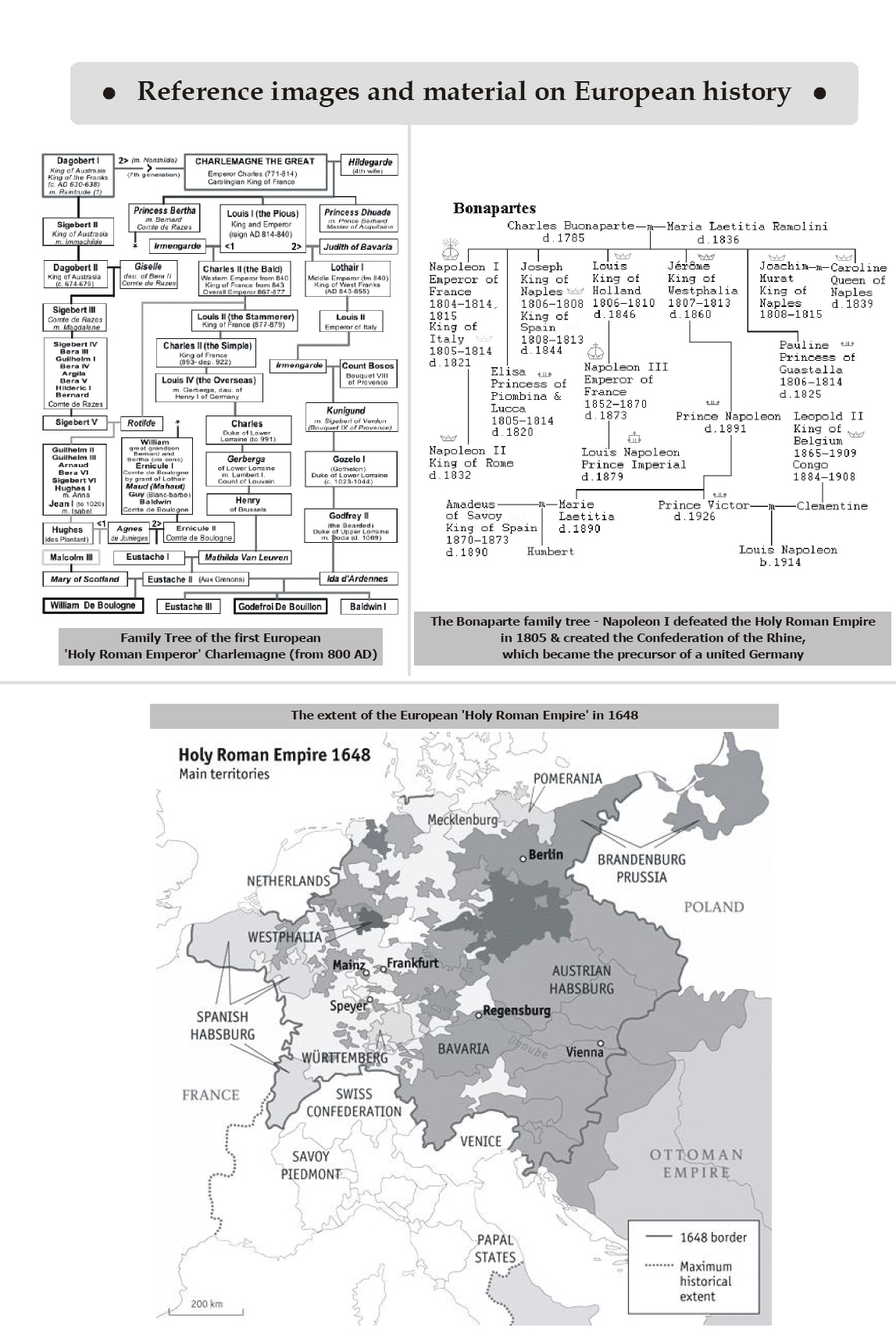

2.2.1 Bismarck's Greater Germany

Bismarck, first Prime Minister of Prussia and then Chancellor of the German Empire (once he had assembled it), set about the construction of Germany through high politics judiciously assisted by war against Austria and France.

His first step was to oust Austria as the prime influence among these German states. He achieved this by engineering a war with Austria in 1866 over disputed territory in the duchy of Holstein (much against the wishes of his own Kaiser). The resulting war lasted just seven weeks - hence its common title 'The Seven Weeks War' - and ended with the complete dominance of the supremely efficient Prussian military. In a peace mediated by the French Emperor, Napoleon III, Bismarck extracted from Austria not only Schleswig and Holstein, but also Hanover, Hesse, Nassau and Frankfurt, creating the North German Federation. As importantly, Bismarck had successfully displaced Austria in the spheres of influence over the many small German states.

Having assembled a united assembly in the north Bismarck determined to achieve the same in the south - and so unite all of the German states under the Prussian banner. Bismarck resolved that war with the French, a common enemy, would attain his aims. He created conditions wherein France would be forced to declare war against Prussia which it did on 19 July 1870. The Prussian army succeeded again and France ceded both Alsace and Lorraine to Prussia.

To protect what he had obtained Bismarck started to assemble a series of key alliances that were to come into play during World War I.

2.2.2 The Three Emperors League & Dual Alliance

He began by negotiating, in 1873, the Three Emperors League, which tied Germany, Austria-Hungary and Russia to each other's aid in time of war. This however only lasted until Russia's withdrawal five years later in 1878, leaving Bismarck with a new Dual Alliance with Austria-Hungary in 1879. This latter treaty promised aid to each other in the event of an attack by Russia, or if Russia aided another power at war with either Germany or Austria-Hungary. Should either nation be attacked by another power, e.g. France, they were to remain - at the very least - benevolently neutral. It was this clause that Austria-Hungary invoked in calling Germany to her aid against Russian support for Serbia (who in turn was protected by treaty with Russia).

2.2.3 The Triple Alliance

Two years after Germany and Austria-Hungary concluded their agreement, Italy was brought into the fold with the signing of the Triple Alliance in 1881. Under the provisions of this treaty, Germany and Austria-Hungary promised to assist Italy if she were attacked by France, and vice versa: Italy was bound to lend aid to Germany or Austria-Hungary if France declared war against either.

Additionally, should any signatory find itself at war with two powers (or more), the other two were to provide military assistance. Finally, should any of the three determine to launch a 'preventative' war ,the others would remain neutral.

One of the chief aims of the Triple Alliance was to prevent Italy from declaring war against Austria-Hungary, towards whom the Italians were in dispute over territorial matters.

2.2.4 A Secret Franco-Italian Alliance

In the event the Triple Alliance was essentially meaningless, for Italy subsequently negotiated a secret treaty with France, under which Italy would remain neutral should Germany attack France - which in the event transpired. In 1914 Italy declared that Germany's war against France was an 'aggressive' one and so entitled Italy to claim neutrality. A year later, in 1915, Italy did enter the First World War, as an ally of Britain, France and Russia.

Austria-Hungary signed an alliance with Romania in 1883, negotiated by Germany, although in the event Romania - after starting World War One as a neutral - eventually joined in with the Allies; as such Austria-Hungary's treaty with Romania was of no actual significance.

2.2.5 Franco-Russian Agreements

Russia allied itself with France. Both powers agreed to consult with the other should either find itself at war with any other nation, or if indeed the stability of Europe was threatened. This rather loosely worded agreement was solidified in 1892 with the Franco-Russian Military Convention, aimed specifically at counteracting the potential threat posed by the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy.

In short, should France or Russia be attacked by one of the Triple Alliance signatories - or even should a Triple Alliance power mobilise against either (where to mobilise meant simply placing a nation on a war footing preparatory to the declaration of hostilities), the other power would provide military assistance.

2.2.6 British emergence from splendid isolation

Meanwhile, Britain was awakening to the emergence of Germany as a great European power - and a colonial power at that. Kaiser Wilhelm's successor, Wilhelm II, proved far more ambitious in establishing "a place in the sun" for Germany. With the effective dismissal of Bismarck, the new Kaiser was determined to establish Germany as a great colonial power in the Pacific and, most notably, in Africa.

Wilhelm, encouraged by his naval minister Alfred Von Tirpitz, embarked upon a massive shipbuilding exercise intended to produce a naval fleet the equal of Britain's, unarguably by far and away the world's largest.

Britain, at that time the greatest power of all, took note. In the early years of the twentieth century, in 1902, she agreed a military alliance with Japan, aimed squarely at limiting German colonial gains in the East.

She also responded by commissioning a build-up in her own naval strength, determined to outstrip Germany. In this she succeeded, building in just 14 months - a record - the enormous Dreadnought battleship, completed in December 1906. By the time war was declared in 1914 Germany could muster 29 battleships, Britain 49.

Despite her success in the naval race, Germany's ambitions succeeded at the very least in pulling Britain into the European alliance system - and, it has been argued, brought war that much closer.

2.2.7 Cordial Agreements: Britain, France and Russia

Two years later Britain signed the Entente Cordiale with France. This 1904 agreement finally resolved numerous leftover colonial squabbles. More significantly, although it did not commit either to the other's military aid in time of war, it did offer closer diplomatic co-operation generally.

Three years on, in 1907, Russia formed what became known as the Triple Entente (which lasted until World War One) by signing an agreement with Britain, the Anglo-Russian Entente.

Together the two agreements formed the three-fold alliance that lasted and effectively bound each to the other right up till the outbreak of world war just seven years later.

Again, although the two Entente agreements were not militarily binding in any way, they did place a "moral obligation" upon the signatories to aid each other in time of war.

It was chiefly this moral obligation that drew Britain into the war in defence of France, although the British pretext was actually the terms of the largely forgotten 1839 Treaty of London that committed the British to defend Belgian neutrality (discarded by the Germans as "a scrap of paper" in 1914, when they asked Britain to ignore it).

In 1912 Britain and France did however conclude a military agreement, the Anglo-French Naval Convention, which promised British protection of France's coastline from German naval attack, and French defence of the Suez Canal.

Such were the alliances between the major continental players.

The war was a global conflict. Thirty-two nations were eventually involved. Twenty-eight of these constituted the Allied and Associated Powers, whose principal belligerents were the British Empire, France, Italy, Russia, Serbia, and the United States of America. They were opposed by the Central Powers: Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, Germany, and the Ottoman Empire.

2.3 The Assasination

On June 28, 1914, the archduke of Austria, Franz Ferdinand, and his wife were on an official visit to the city of Sarajevo in Bosnia-Herzegovina, a Serb-dominated province of Austria-Hungary. During the visit, Serbian militants, seeking independence for the territory, made two separate attempts on the archduke's life. In the first attempt, they threw a bomb at his car shortly after he arrived in town, but the bomb bounced off the car and failed to kill or injure the intended victim.

Later that day, while the archduke was en route to a hospital to visit an officer wounded by the bomb, his driver turned down a side street where Gavrilo Princip, a nineteen-year-old militant Bosnian Serb who had been part of the assassination attempt that morning, happened to be standing. Seizing the opportunity, Princip stepped up to the car's window and shot both the archduke and his wife at point-blank range.

The archduke's assassination had an incendiary effect throughout Central Europe. Tensions between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, which had already been rising for several years over territorial disputes, escalated further. Despite limited evidence, Austria-Hungary blamed the Serbian government for the assassination. Furthermore, it blamed Serbia for seeding unrest among ethnic Serbs in Bosnia-Herzegovina, a province of Austria-Hungary that shared a border with Serbia.

3.0 The First Phase

3.1 The beginning of hostilities

The assassination set of a series of chain reactions which due to the alliances and the Balkan region spiralled out of control. The following is the sequence of events after the assassination:

July 5 Austria requests and receives Germany's "blank check," pledging unconditional support if Russia enters the war

July 23 Austria issues ultimatum to Serbia

July 25 Serbia responds to ultimatum; Austrian ambassador to Serbia immediately leaves Belgrade France promises support to Russia in the event of war

July 28 Austria declares war on Serbia

July 30 Russia orders general mobilization of troops

August 1 Germany declares war on Russia. France and Germany order general mobilization

August 3 Germany declares war on France

August 4 Britain declares war on Germany

3.2 The progress of the War

Other major belligerents took their time and waited upon events. Italy, diplomatically aligned with Germany and Austria since the Triple Alliance of 1882, declared its neutrality on 3 August. In the following months it was ardently courted by France and Britain. On 23 May 1915 the Italian government succumbed to Allied temptations and declared war on Austria-Hungary in pursuit of territorial aggrandizement. Bulgaria invaded Serbia on 7 October 1915 and Serbia was overrun. The road to Constantinople was opened to the Central Powers. Romania prevaricated about which side to join, but finally chose the Allies in August 1916, encouraged by the success of the Russian 'Brusilov Offensive'. It was a fatal miscalculation. The German response was swift and decisive. Romania was rapidly overwhelmed by two invading German armies and its rich supplies of wheat and oil did much to keep Germany in the war for another two years. Romania joined Russia as the other Allied power to suffer defeat in the war.

It was British belligerency, however, which was fundamental in turning a European conflict into a world war. Britain was the world's greatest imperial power. The British had world-wide interests and world-wide dilemmas. They also had world-wide friends. Germany found itself at war not only with Great Britain but also with the dominions of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa and with the greatest British imperial possession, India. Concern for the defence of India helped bring the British into conflict with the Ottoman Empire in November 1914 and resulted in a major war in the Middle East. Most important of all, perhaps, Britain's close political, economic, and cultural ties with the United States of America, if they did not ensure that nation's eventual entry into the war, certainly made it possible. The American declaration of war on Germany on 6 April 1917 was a landmark not only in the history of the United States but also in that of Europe and the world, bringing to an end half a millennium of European domination and ushering in 'the American century'.

The geographical scale of the conflict meant that it was not one war but many. On the Western Front in France and Belgium the French and their British allies, reinforced from 1917 onwards by the Americans, were locked in a savage battle of attrition against the German army. Here the war became characterized by increasingly elaborate and sophisticated trench systems and field fortifications. Dense belts of barbed wire, concrete pillboxes, intersecting arcs of machine-gun fire, and accumulating masses of quick-firing field and heavy artillery rendered manœuvre virtually impossible. Casualties were enormous.

The first phase of the war in the west lasted until November 1914. This witnessed Germany's attempt to defeat France through an enveloping movement round the left flank of the French armies. The plan met with initial success. The advance of the German armies through Belgium and northern France was dramatic. The French, responding with an offensive in Lorraine, suffered an almost catastrophic national defeat. France was saved by the iron nerve of its commander-in-chief, General J. J. C. Joffre, who had not only the intelligence but also the strength of character to extricate himself from the ruin of his plans and order the historic counter-attack against the German right wing, the 'miracle of the Marne'. The German armies were forced to retreat and to entrench. Their last attempt at a breakthrough was stopped by French and British forces near the small Flemish market town of Ypres in November. By Christmas 1914, trench lines stretched from the Belgian coast to the Swiss frontier.

Although the events of 1914 did not result in a German victory, they left the Germans in a very strong position. The German army held the strategic initiative. It was free to retreat to positions of tactical advantage and to reinforce them with all the skill and ingenuity of German military engineering. Enormous losses had been inflicted on France. Two-fifths of France's military casualties were incurred in 1914. These included a tenth of the officer corps. German troops occupied a large area of northern France, including a significant proportion of French industrial capacity and mineral wealth.

3.3 The second phase

The Second Phase of the war lasted from November 1914 until March 1918. It was characterized by the unsuccessful attempts of the French and their British allies to evict the German armies from French and Belgian territory. During this period the Germans stood mainly on the defensive, but they showed during the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April-25 May 1915), and more especially during the Battle of Verdun (21 February-18 December 1916), a dangerous capacity to disrupt their enemies' plans.

The French made three major assaults on the German line: in the spring of 1915 in Artois; in the autumn of 1915 in Champagne; and in the spring of 1917 on the Aisne (the 'Nivelle Offensive'). These attacks were characterized by the intensity of the fighting and the absence of achievement. Little ground was gained. No positions of strategic significance were captured. Casualties were severe. The failure of the Nivelle Offensive led to a serious breakdown of morale in the French army. For much of the rest of 1917 it was incapable of major offensive action.

The British fared little better. Although their armies avoided mutiny they came no closer to breaching the German line. During the battles of the Somme (1 July-19 November 1916) and the Third Battle of Ypres (31 July-12 November 1917) they inflicted great losses on the German army at great cost to themselves, but the German line held and no end to the war appeared in sight.

3.4 The final phase

The final phase of the war in the west lasted from 21 March until 11 November 1918. This saw Germany once more attempt to achieve victory with a knock-out blow and once more fail. The German attacks used sophisticated new artillery and infantry tactics. They enjoyed spectacular success. The British 5th Army on the Somme suffered a major defeat. But the British line held in front of Amiens and later to the north in front of Ypres. No real strategic damage was done. By midsummer the German attacks had petered out. The German offensive broke the trench deadlock and returned movement and manœuvre to the strategic agenda. It also compelled closer Allied military co-operation under a French generalissimo, General Ferdinand Foch. The Allied counter-offensive began in July. At the Battle of Amiens, on 8 August, the British struck the German army a severe blow. For the rest of the war in the west the Germans were in retreat.

3.5 United States enters the War

US had since long maintained its neutrality during the war. Three key reasons are usually mentioned for US intervention in the war.

- In May 1915, a German submarine sank the British ocean liner Lusitania , killing 128 U.S. citizens.

- The American cargo ship Housatonic was sunk by a German U-boat on February 3, 1917.

- On March 1, 1917, the text of the Zimmermann telegram (a proposal from Germans to Mexicans asking them to join the War if US joins it) appeared on the front pages of American newspapers, and in a heartbeat, American public opinion shifted in favor of entering the war.

On April 2, Wilson appeared before Congress and requested a declaration of war. Congress responded within days, officially declaring war on Germany on April 6, 1917.

All through the summer of 1917, U.S. troops were ferried across the Atlantic, first to Britain and then on to France, where they came under the leadership of General John J. Pershing. The first public display of the troops came on July 4, when a large U.S. detachment held a symbolic march through Paris to the grave of the Marquis de Lafayette, the French aristocrat who had fought alongside the United States during the American Revolution. Though U.S. leaders had not planned major military involvement until the summer of 1918, some forces saw combat in the fall of 1917. The first American fatalities on the ground in Europe occurred on September 4, when four soldiers were killed during a German air raid. The first full-fledged combat involving U.S. troops happened on November 2-3, 1917, at Bathelémont, France; three were killed and twelve were taken as German prisoners of war.

3.5 Russia exits the War

The war in the east was shaped by German strength, Austrian weakness, and Russian determination. German military superiority was apparent from the start of the war. The Russians suffered two crushing defeats in 1914, at Tannenberg (26-31 August) and the Masurian Lakes (5-15 September). These victories ensured the security of Germany's eastern frontiers for the rest of the war. They also established the military legend of Field-Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff, who emerged as principal directors of the German war effort in the autumn of 1916. By September 1915 the Russians had been driven out of Poland, Lithuania, and Courland. Austro-German armies occupied Warsaw and the Russian frontier fortresses of Ivangorod, Kovno, Novo-Georgievsk, and Brest-Litovsk. These defeats proved costly to Russia.

Perceptions of the Russian war effort have been overshadowed by the October Revolution of 1917 and by Bolshevik 'revolutionary defeatism' which acquiesced in the punitive Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (14 March 1918) and took Russia out of the war. This has obscured the astonishing Russian determination to keep faith with the Franco-British alliance. Without the Russian contribution in the east it is far from certain that Germany could have been defeated in the west. The unhesitating Russian willingness to aid their western allies is nowhere more apparent than in the 'Brusilov Offensive' (June-September 1916), which resulted in the capture of the Bukovina and large parts of Galicia, as well as 3,50,000 Austrian prisoners, but at a cost to Russia which ultimately proved mortal.

On November 26, 1917, the Bolsheviks issued a call for a halt to hostilities on all fronts and requested that all sides immediately make arrangements to sign an armistice. This idea was not well received by France and Britain, who still intended to push the Germans out of their lands. When Russia received no response, it made another call, warning that if no one responded, Russia would make a separate peace. When there still was no response, the Bolsheviks, in an effort to embarrass the Allied forces, published a series of secret treaties that Russia had made with the Allies.

After several days of negotiations, a cease-fire was declared on December 15, 1917. A formal peace treaty, however, proved more difficult to achieve. It took months of negotiations, and Russia lost an enormous amount of territory. Russia's land losses included Finland, Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, the Ukraine, Belarus, Bessarabia, and the Caucasus region, along with some of the coal-mining regions of southern Russia.

The war had drained Russia: 1.7 million of its soldiers had died in battle, and 3 million Russian civilians had perished as well. Moreover, the country was left in chaos, as there were still large groups of people remaining in Russia who opposed the Bolsheviks' rule. Some sought to bring back the tsar; others favored a democratic government akin to the one promised by the provisional government that the Bolsheviks had overthrown. In the end, though Russia got out of World War I, the civil war that soon started within the country turned out to be even more costly for its people than World War I had been.

4.0 Endgame

With its newly arrived forces from the eastern front, Germany enjoyed superiority in numbers on the western front for the first time since the earliest days of the war. Nonetheless, all sides, including Germany, were exhausted. Their strength was limited, and fresh troops from the United States would soon be ready to join the fight on the Allied side. If Germany was going to somehow win the war, now was the time.

Germany therefore poured all of its remaining resources into a massive offensive that began in the early morning hours of March 21, 1918. The goal was to push across the river Somme and then on to Paris. Like most land battles in World War I, the offensive began with a prolonged artillery barrage. In this case it lasted for five hours and included a heavy concentration of poison gas shells along with the usual explosive ordinance. When the German troops moved forward through a combination of heavy fog and poison gas clouds, visibility was near zero, and soldiers on both sides were largely unable to distinguish friendly from enemy forces. By midday, the fog had lifted, and a furious air battle took place over the soldiers' heads while the Germans relentlessly pounded the Allies.

German momentum continued for another five days until a British advance halted the Germans at Moreuil Wood on March 30. The Allies pushed the Germans back for several days more, until the initiative was turned around once more at the Battle of Lys, which began on April 9, 1918. At Lys, the British and French began to lose ground once more, and the Germans recaptured places (such as Passchendaele and Messines) that the Allies had won in hard-fought battles the previous year.

Only the United States, it seemed, held the power to shift the balance, but more than a year had passed since the U.S. declaration of war, with little tangible result. Although hundreds of thousands of American troops had been transported to Europe, very few of them had actually participated in combat.

At a meeting of the Supreme War Council of Allied Leaders on May 2, 1918, General John J. Pershing, the commander of American forces in Europe, agreed to a compromise, pledging to send 1,30,000 troops that month and several hundred thousand more in the coming months to fight on the front with the French and British forces. This commitment mean that roughly one-third of the American forces present in Europe would see action that summer. U.S. leaders estimated that the rest, however, would not be organized, trained, and ready to fight until the late spring of 1919.

4.1 Turmoil in the East

Although Russia was fully out of the war, much unfinished business remained in the territories along the old eastern front. On May 7, 1918, Romania signed a peace treaty with the Central Powers, giving up control of the mouth of the Danube River along the Black Sea coast. At the same time, German troops advanced to the southeast, through the Ukraine, southern Russia, and on to the Caucasus region. The Bolsheviks still did not have an effective hold on this region, so the Germans were able to proceed largely unchallenged.

On May 12, Germany and Austria-Hungary signed an agreement to share in reaping economic benefits from the Ukraine. Barely a week later, however, Austria-Hungary experienced the first in a series of mutinies in its army, carried out by nationalist groups. The first mutiny involved a group of Slovenes; almost as soon as it was suppressed, other mutinies broke out, led in turn by Serbs, Rusyns (Ruthenians), and Czechs.

4.2 The Battle of Cantigny: The first American victory

By the end of May 1918, several thousand American troops had appeared on the front ready to fight, arriving just in time to meet the latest German offensive. The U.S. forces were involved in several battles, most notably at Cantigny, on the Somme. Here, 4,000 American soldiers attacked German forces on May 28, while the French provided cover with tanks, airplanes, and artillery. They successfully liberated the town of Cantigny and then held the line during three successive days of German counterattacks. U.S. forces suffered over 1,000 casualties during the engagement.

4.3 The Allied counteroffensive

Throughout June and early July 1918, the Germans attempted a series of offensive actions, still trying to break through the Allied defense lines in France. The lines held, however, in part due to the newly provided American reinforcements.

On June 3, a German attack at Château-Thierry was stymied by intelligence that the Allies gained from German prisoners of war. Knowing of the German plans in advance, the French created a false front line, complete with trenches. The German artillery barrage ended up landing on a set of trenches that were largely empty, and when the German soldiers rushed forward, they found themselves facing mostly fresh and unfazed Allied soldiers who opened fire upon them, leaving the Germans in disarray. Nonetheless, the Germans continued the attack over the next two days, once again threatening Paris.

The Allies responded on June 6 with a counterattack of their own, using combined forces from France, Britain, Italy, and the United States. The attack was devastating, killing over 30,000 German soldiers in twenty days. Although the battle continued for many weeks, the Germans' will to fight was shattered, and Kaiser Wilhelm II knew that the end was looming. German troops were losing ground every day, and the Allies intensified their attacks with every opportunity. The momentum stayed with them, and they steadily drove the Germans back during all of August and September.

4.4 Turkey in retreat

In the Near East, meanwhile, the tide had turned in the war with the Ottoman Empire since the devastating British defeats in Gallipoli and Mesopotamia back in 1916. Since then, Britain had captured Baghdad along with all of Mesopotamia. Farther south, on the Arabian Peninsula, revolts by desert tribesmen had broken Turkey's long-lasting grip on the region.

In December 1917, the British captured the city of Jerusalem in Palestine and slowly began advancing toward Turkey proper. Finally, on September 19, 1918, the British launched a direct attack on the Turkish front at Megiddo and won a major victory that forced the Turks into a full-scale retreat. By mid-October, Turkey was asking for peace terms.

4.5 The final phase of combat

By the spring of 1918, both sides' armies were exhausted from years of fighting and had little reason to hope that an end would soon come. While there were some hints of peace discussions late in the summer, the political and military leaders of all the remaining warring countries were actively planning combat operations intended to last well into 1919.

Russia's exit from the war gave the Germans a renewed hope of achieving victory, just as the appearance of American troops in Europe gave similar hope to the French and British; however, neither of these events really turned the tide. Rather, they effectively balanced each other out, while the catastrophic influenza outbreak placed a heavy burden on both sides. Ultimately, the real trigger for the end of the war appears to have come from the mass mutinies within the Austro-Hungarian and German militaries.

5.0 The Collapse

5.1 The dissolution of Austria-Hungary

On October 27, 1918, Austria approached the Allies independently for an armistice and ordered the Austrian army to retreat the same day. On October 29, Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes proclaimed the establishment of a southern Slavic state to be called Yugoslavia. On October 30, an Austrian delegation arrived in Italy to surrender unconditionally. That same day, Hungary formally declared its independence. On November 3, all the terms of the Austrian armistice were in place, and on the following day, Austria-Hungary formally ceased to exist.

5.2 The collapse of the Ottoman Empire

On October 14, 1918, Sultan Mehmed VI of the Ottoman Empire, having suffered heavy territorial losses over the past year and facing a British invasion of Turkey proper, requested peace terms. An armistice was signed on October 30. One of its terms was that the Dardanelles be opened immediately to Allied ships. In the coming months, most of the territory of the Ottoman Empire would be redistributed under the trusteeship of various Allied forces and eventually reorganized into independent countries.

5.3 The collapse of Germany

In the early days of November 1918, the situation in Germany deteriorated from unstable to outright chaotic. Prince Max von Baden proved ineffective at negotiating favorable terms for a German armistice, and unrest within the military grew, especially in the navy, where mutinies were becoming widespread. Kaiser Wilhelm II, who by this point was in hiding in the Belgian resort town of Spa, found himself under rapidly increasing pressure to abdicate, which he stubbornly refused to do.

On November 7, Max dispatched a group of German delegates by train to the secluded location of Compiègne, France, to negotiate an armistice. The delegation arrived on the morning of November 9, and negotiation promptly began. That same day, Prince Max took the step of announcing Wilhelm II's abdication of the German throne-without the now-delusional Kaiser's agreement. Prince Max himself then resigned, and separate left-wing political groups respectively proclaimed the establishment of a German Soviet Republic and a German Socialist Republic, though neither would actually come to be.

5.4 The Armistice

Finally, on November 11, at 5:10 a.m., the armistice with Germany was signed. Hostilities officially ended at 11:00 a.m. that day. Thus, the end of World War I is generally reported to have come on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918. It would be more than seven months; however, before formal peace treaties would finalize the arrangements among all the various warring nations.

5.5 The Treaty of Versailles

Just as it had begun, World War I ended with complicated diplomatic negotiations. It took many months, but the treaty defining Germany's present and future existence was signed at Versailles on June 28, 1919.

For Germany, it was a day of complete humiliation. The country was required to accept losses of territory, including Alsace-Lorraine and much of present-day Poland. Germany would retain the border region of the Rhineland but was strictly forbidden to develop the area militarily. Germany also had to agree to pay massive war reparations that would require half a century to fulfill. Finally, Germany was forced to publicly acknowledge and accept full responsibility for the entire war. This stipulation was a hard pill for many Germans to swallow, and indeed it was a blatant untruth.

5.6 The legacy of the War

World War I began with a cold-blooded murder, diplomatic intrigue, and overconfident guesses about what the other side would do. Contemporary accounts report that there was even a sense of excitement and adventure in the air, as some seemed to envision the war more as a chance to try out the newest technological innovations than anything else. Five tragic years later, the reality of the war was unfathomably different: tens of millions dead, entire countries in ruins, and economies in shambles. Millions of soldiers had been drawn into the war, many from faraway colonies and many with little more than an inkling of what it was they were fighting for.

The Treaty of Versailles, rather than fix these problems, imposed bewilderingly harsh terms upon Germany, forcing that nation to accept full financial and diplomatic responsibility for the entire war. In the peace treaties ending most previous European wars, each side had accepted its losses, claimed its spoils, shaken hands, and then moved on. After World War I, however, the German people were humiliated, impoverished, and left with nothing to hope for but more of the same. Internally, Germany became a tumultuous place, teetering on the brink of violent revolutions from both the right and the left and vulnerable to take over from extremist elements like the Nazi Party. Indeed, just a few decades would prove that the Allies had gone overboard with the punishments they inflicted on Germany - a misjudgment that created precisely the conditions required for launching Europe into the center of an even more horrible war.