Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - being learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

The French Revolution

1.0 Introduction

A watershed event in modern European history, the French Revolution began in 1789 and ended in the late 1790s with the ascent of Napoleon Bonaparte. During this period, French citizens abruptly and suddenly razed and redesigned their country's political landscape, uprooting centuries-old institutions such as absolute monarchy and the feudal system. Like the American Revolution before it, the French Revolution was influenced by Enlightenment ideals, particularly the concepts of popular sovereignty and inalienable rights. Although it failed to achieve all of its goals and at times degenerated into a chaotic bloodbath, the movement played a critical role in shaping modern nations by showing the world the power inherent in the will of the people.

The revolutionary movement occurred between 1787 and 1799 and reached its first climax there in 1789. Hence the conventional term "Revolution of 1789," denotes the end of the ancient régime in France and also distinguishes that event from the later French revolutions of 1830 and 1848.

2.0 Causes of the French Revolution

Although historians disagree on the causes of the Revolution, the following reasons are commonly adduced:

- The increasingly prosperous elite of wealthy commoners - merchants, manufacturers, and professionals, often called the bourgeoisie - produced by the 18th century's economic growth resented its exclusion from political power and positions of honour;

- The peasants were acutely aware of their situation and were less and less willing to support the anachronistic and burdensome feudal system;

- The philosophers, who advocated social and political reform, had been read more widely in France than anywhere else, thereby affecting popular sentiment;

- French participation in the American Revolution had driven the government to the brink of bankruptcy; and

- Crop failures in much of the country in 1788, coming on top of a long period of economic difficulties, made the population very restless.

Some other reasons which are usually cited, are:

- International: struggle for hegemony and Empire building outstrips the fiscal resources of the state

- Political conflict: conflict between the Monarchy and the nobility over the "reform" of the tax system led to paralysis and bankruptcy

- The Enlightenment: impulse for reform intensifies political conflicts; reinforces traditional aristocratic constitutionalism, one variant of which was laid out in Montequieu's Spirit of the Laws; introduces new notions of good government, the most radical being popular sovereignty, as in Rousseau's Social Contract [1762]; the attack on the regime and privileged class by the Literary Underground of “Grub Street”; the broadening influence of public opinion.

- Social antagonisms between two rising groups: the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie

- Ineffective rule of Louis XVI, the monarch

- Economic hardship: especially the agrarian crisis of 1788-89 generated popular discontent, and disorders caused by food shortages further aggravated the situation.

3.0 THE FINANCIAL CRISIS IN FRANCE

The French Monarchy and Parlements

The French royalty in the years prior to the French Revolution were a study in corruption and excess. France had long subscribed to the idea of divine right, which maintained that kings were selected by God and thus perpetually entitled to the throne. This doctrine resulted in a system of absolute rule and provided the commoners with absolutely no possibility of any input into the governance of their country.

In addition, there was no universal law in France at the time. Rather, laws varied by region and were enforced by the local parlements (provincial judicial boards), guilds, or religious groups. Moreover, each of those sovereign courts had to approve any royal decrees by the king if these decrees were to come into effect. As a result, the king was virtually powerless to do anything that would have a negative effect on any regional government. Ironically, this “checks and balances" system operated in a government rife with corruption and operating without the support of the majority.

3.1 Power abuses and unfair taxation

The monarchs of the Bourbon dynasty (The House of Bourbon), the French nobility, and the clergy became increasingly egregious in their abuses of power in the late 1700s. They bound the French peasantry into compromising feudal obligations and refused to contribute any tax revenue to the French government. This blatantly unfair taxation arrangement did little to endear the aristocracy to the common people.

3.2 France's debt problems

A number of ill-advised financial maneuvers in the late 1700s worsened the financial situation of the already cash-strapped French government. France's prolonged involvement in the Seven Years' War of 1756-1763 drained the treasury, as did the country's participation in the American Revolution of 1775-1783. Aggravating the situation was the fact that the government had a sizable army and navy to maintain, which was an expenditure of particular importance during those volatile times. Moreover, in the typical indulgent fashion that so irked the common folk, mammoth costs associated with the upkeep of King Louis XVI's extravagant palace at Versailles and the frivolous spending of the queen, Marie-Antoinette, did little to relieve the growing debt. These decades of fiscal irresponsibility were one of the primary factors that led to the French Revolution. France had long been recognized as a prosperous country, and were it not for its involvement in costly wars and its aristocracy's extravagant spending, it might have remained one.

(In all fairness, historians say that a lot that was attributed to the Queen Marie-Antoniette was never said by her!)

3.3 Charles de Calonne

Finally, in the early 1780s, France realized that it had to address the problem, and fast. First, Louis XVI appointed Charles de Calonne as Controller General of Finances in 1783. Then, in 1786, the French government, worried about unrest should it to try to raise taxes on the peasants, yet reluctant to ask the nobles for money, approached various European banks in search of a loan. By that point, however, most of Europe knew the depth of France's financial woes, so the country found itself with no credibility.

Louis XVI asked Calonne to evaluate the situation and propose a solution. Charged with auditing all of the royal accounts and records, Calonne found a financial system in shambles. Independent accountants had been put in charge of various tasks regarding the acquisition and distribution of government funds, which made the tracking of such transactions very difficult. Furthermore, the arrangement had left the door wide open to corruption, enabling many of the accountants to dip into government funds for their own use. As for raising new money, the only system in place was taxation. At the time, however, taxation only applied to peasants. The nobility were tax-exempt, and the parlements would never agree to across-the-board tax increases.

3.4 The Assembly of Notables

Calonne finally convinced Louis XVI to gather the nobility together for a conference, during which Calonne and the King could fully explain the tenuous situation facing France. This gathering, dubbed the Assembly of Notables, turned out to be a virtual who's who of people who didn't want to pay any taxes. After giving his presentation, Calonne urged the notables either to agree to the new taxes or to forfeit their exemption to the current ones. Unsurprisingly, the notables refused both plans and turned against Calonne, questioning the validity of his work. He was dismissed shortly thereafter, leaving France's economic prospects even grimmer than before.

3.5 Revolution on the horizon

By the late 1780s, it was becoming increasingly clear that the system in place under the Old Regime in France simply could not last. It was too irresponsible and oppressed too many people. Furthermore, as the result of the Enlightenment, secularism was spreading in France, religious thought was becoming divided, and the religious justifications for rule - divine right and absolutism - were losing credibility. The aristocracy and royalty, however, ignored these progressive trends in French thought and society. Rather, the royals and nobles adhered even more firmly to tradition and archaic law. As it would turn out, their intractability would cost them everything that they were trying to preserve.

3.6 The Bourgeoisie

Although many accounts of the French Revolution focus on the French peasantry's grievances - rising food prices, disadvantageous feudal contracts, and general mistreatment at the hands of the aristocracy - these factors actually played a limited role in inciting the Revolution. For all of the hardships that they endured, it wasn't the peasants who jump-started the Revolution. Rather, it was the wealthy commoners - the bourgeoisie - who objected most vocally to the subpar treatment they were receiving. The bourgeoisie were generally hardworking, educated men who were well versed in the enlightened thought of the time. Although many of the wealthier members of the bourgeoisie had more money than some of the French nobles, they lacked elite titles and thus were subjected to the same treatment and taxation as even the poorest peasants. It was the bourgeoisie that would really act as a catalyst for the Revolution, and once they started to act, the peasants were soon to follow.

4.0 The Phases of the Revolt

4.1 Aristocratic revolt, 1787-89

As mentioned earlier, the Revolution took shape in France when the Controller General of Finances, Charles-Alexandre de Calonne, arranged the summoning of an assembly of "notables" (prelates, great noblemen, and a few representatives of the bourgeoisie) in February 1787 to propose reforms designed to eliminate the budget deficit by increasing the taxation of the privileged classes. The assembly refused to take responsibility for the reforms and suggested the calling of the Estates-General, which represented the clergy, the nobility, and the Third Estate (the commoners) and which had not met since 1614. The efforts made by Calonne's successors to enforce fiscal reforms in spite of resistance by the privileged classes led to the so-called revolt of the "aristocratic bodies," notably that of the parlements (the most important courts of justice), whose powers were curtailed by the edict of May 1788. During the spring and summer of 1788, there was unrest among the populace in Paris, Grenoble, Dijon, Toulouse, Pau, and Rennes. The king, Louis XVI, had to yield; reappointing reform-minded Jacques Necker as the finance minister, he promised to convene the Estates-General on May 5, 1789. He also, in practice, granted freedom of the press, and France was flooded with pamphlets addressing the reconstruction of the state. The elections to the Estates-General, held between January and April 1789, coincided with further disturbances, as the harvest of 1788 had been a bad one. There were practically no exclusions from the voting; and the electors drew up cahiers de doléances, which listed their grievances and hopes. They elected 600 deputies for the Third Estate, 300 for the nobility, and 300 for the clergy.

4.2 Events of 1789

The Estates-General met at Versailles on May 5, 1789. They were immediately divided over a fundamental issue: should they vote by head, giving the advantage to the Third Estate, or by estate, in which case the two privileged orders of the realm might outvote the third? On June 17 the bitter struggle over this legal issue finally drove the deputies of the Third Estate to declare themselves the National Assembly; they threatened to proceed, if necessary, without the other two orders. They were supported by many of the parish priests, who outnumbered the aristocratic upper clergy among the church's deputies. When royal officials locked the deputies out of their regular meeting hall on June 20, they occupied the king's indoor tennis court (jeu de paume) and swore an oath (the Tennis Court oath) not to disperse until they had given France a new constitution. The king grudgingly gave in and urged the nobles and the remaining clergy to join the assembly, which took the official title of National Constituent Assembly on July 9; at the same time, however, he began gathering troops to dissolve it.

These two months of prevarication at a time when the problem of maintaining food supplies had reached its climax infuriated the towns and the provinces. Rumours of an "aristocratic conspiracy" by the king and the privileged to overthrow the Third Estate led to the Great Fear of July 1789, when the peasants were nearly panic-stricken. The gathering of troops around Paris and the dismissal of Necker provoked insurrection in the capital.

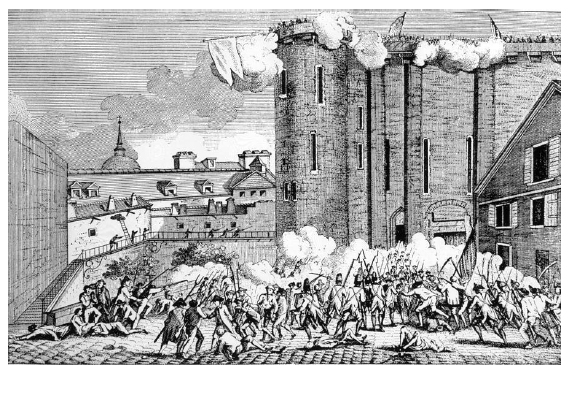

4.3 The storming of the Bastille

On 14 July 1789, a state prison on the east side of Paris, known as the Bastille, was attacked by an angry and aggressive mob. The prison had become a symbol of the monarchy's dictatorial rule, and the event became one of the defining moments in the Revolution that followed.

A medieval fortress, the Bastille's eight 30-metre-high towers, dominated the Parisian skyline. When the prison was attacked it actually held only seven prisoners, but the mob had not gathered for them: it had come to demand the huge ammunition stores held within the prison walls. When the prison governor refused to comply, the mob charged and, after a violent battle, eventually took hold of the building. The governor was seized and killed, his head carried round the streets on a spike. The storming of the Bastille symbolically marked the beginning of the French Revolution.

In the provinces, the Great Fear of July led the peasants to rise against their lords. The nobles and the bourgeois now took fright. The National Constituent Assembly could see only one way to check the peasants; on the night of August 4, 1789, it decreed the abolition of the feudal regime and of the tithe (1/10 th paid as taxes).

4.4 The Rights of Man

"Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité" (Liberty, Equality, Brotherhood), the slogan of France is a part of their national heritage.

The notions of liberty, equality and brotherhood, associated by Fénelon at the end of the 17th century, became more widespread during the Age of Enlightenment.

The slogan "Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité" stems from the French Revolution: it appeared in public debate before the proclamation of the First Republic as of 1790.

Like many revolutionary symbols, the slogan fell into disuse during the Empire. It reappeared during the Revolution of 1848, with a religious dimension: the priests celebrated the Brotherhood of Christ and blessed the trees of liberty that were planted at that time. When the Constitution of 1848 was drafted, the slogan "Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité" was defined as a "principle" of the Republic.

It was rejected during the Second Empire, but finally became established under the 3rd Republic. There is still some resistance, even among partisans of the Republic: solidarity is sometimes preferred to equality, which implies social levelling, and the Christian connotation of brotherhood is not always unanimously accepted.

The slogan was inscribed on the pediments of public buildings for the celebration of 14 July 1880. It appears in the Constitutions of 1946 and 1958 and is now an integral part of French national heritage. It can be found on widely distributed objects such as coins and stamps.

The decrees of August 4 and the Declaration were such innovations that the king refused to sanction them. The Parisians rose again and on October 5 marched to Versailles. The next day they brought the royal family back to Paris. The National Constituent Assembly followed the court, and in Paris it continued to work on the new constitution.

The French population participated actively in the new political culture created by the Revolution. Dozens of uncensored newspapers kept citizens abreast of events, and political clubs allowed them to voice their opinions. Public ceremonies such as the planting of "trees of liberty" in small villages and the Festival of Federation, held in Paris in 1790 on the first anniversary of the storming of the Bastille, were symbolic affirmations of the new order.

5.0 The new regime

The National Constituent Assembly completed the abolition of feudalism, suppressed the old “orders”, established civil equality among men (at least in metropolitan France, since slavery was retained in the colonies), and made more than half the adult male population eligible to vote, although only a small minority met the requirement for becoming a deputy. The decision to nationalize the lands of the Roman Catholic church in France to pay off the public debt led to a widespread redistribution of property. The bourgeoisie and the peasant landowners were undoubtedly the chief beneficiaries, but some farm workers also were able to buy land. Having deprived the church of its resources, the assembly then resolved to reorganize the church, enacting the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which was rejected by the Pope and by many of the French clergy. This produced a schism that aggravated the violence of the accompanying controversies.

The complicated administrative system of the ancient régime was swept away by the National Constituent Assembly, which substituted a rational system based on the division of France into départements (administrative divisions), districts, cantons, and communes administered by elected assemblies. The principles underlying the administration of justice were also radically changed, and the system was adapted to the new administrative divisions. Significantly, the judges were to be elected.

The National Constituent Assembly tried to create a monarchical regime in which the legislative and executive powers were shared between the king and an assembly. This regime might have worked if the king had really wanted to govern with the new authorities, but Louis XVI was weak and vacillating and was the prisoner of his aristocratic advisers. On June 20-21, 1791, he tried to flee the country, but he was stopped at Varennes and brought back to Paris.

6.0 Counter revolution, regicide, and the Reign of Terror

The events in France gave new hope to the revolutionaries who had been defeated a few years previously in the United Provinces, Belgium, and Switzerland. Likewise, all those who wanted changes in England, Ireland, the German states, the Austrian lands, or Italy looked upon the Revolution with sympathy.

A number of French counterrevolutionaries - nobles, ecclesiastics, and some bourgeois - abandoned the struggle in their own country and emigrated. As “émigrés”, many formed armed groups close to the northeastern frontier of France and sought help from the rulers of Europe. The rulers were at first indifferent to the Revolution but began to worry when the National Constituent Assembly proclaimed a revolutionary principle of international law-namely, that a people had the right of self-determination. In accordance with this principle, the papal territory of Avignon was reunited with France on September 13, 1791. By early 1792 both radicals, eager to spread the principles of the Revolution, and the king, hopeful that war would either strengthen his authority or allow foreign armies to rescue him, supported an aggressive policy. France declared war against Austria on April 20, 1792.

In the first phase of the war (April-September 1792), France suffered defeats; Prussia joined the war in July, and an Austro-Prussian army crossed the frontier and advanced rapidly toward Paris. Believing that they had been betrayed by the king and the aristocrats, the Paris revolutionaries rose on August 10, 1792, occupied Tuileries Palace, where Louis XVI was living, and imprisoned the royal family in the Temple. At the beginning of September, the Parisian crowd broke into the prisons and massacred the nobles and clergy held there. Meanwhile, volunteers were pouring into the army as the Revolution had awakened French nationalism. In a final effort the French forces checked the Prussians on September 20, 1792, at Valmy. On the same day, a new assembly, the National Convention, met. The next day it proclaimed the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the republic.

In the second phase of the war (September 1792-April 1793), the revolutionaries got the better of the enemy. Belgium, the Rhineland, Savoy, and the county of Nice were occupied by French armies. Meanwhile, the National Convention was divided between the Girondins, who wanted to organize a bourgeois republic in France and to spread the Revolution over the whole of Europe, and the Montagnards ("Mountain Men"), who, with Robespierre, wanted to give the lower classes a greater share in political and economic power.

Despite efforts made by the Girondins, in November, evidence of Louis XVI's counterrevolutionary intrigues with Austria and other foreign nations was discovered, and he was put on trial for treason by the National Convention.

The next January, Louis was convicted and condemned to death by a narrow majority. On January 21 1793, he walked steadfastly to the guillotine and was executed. Nine months later, Marie Antoinette was convicted of treason by a tribunal, and on October 16 she followed her husband to the guillotine.

In the spring of 1793, the war entered a third phase, marked by new French defeats. Austria, Prussia, and Great Britain formed a coalition (later called the First Coalition), to which most of the rulers of Europe adhered. France lost Belgium and the Rhineland, and invading forces threatened Paris. These reverses, as those of 1792 had done, strengthened the extremists. The Girondin leaders were driven from the National Convention, and the Montagnards, who had the support of the Paris sansculottes (workers, craftsmen, and shopkeepers), seized power and kept it until 9 Thermidor, year II, of the new French republican calendar (July 27, 1794). The Montagnards were bourgeois liberals like the Girondins but under pressure from the sansculottes, and, in order to meet the requirements of defense, they adopted a radical economic and social policy. They introduced the Maximum (government control of prices), taxed the rich, brought national assistance to the poor and to the disabled, declared that education should be free and compulsory, and ordered the confiscation and sale of the property of émigrés. These exceptional measures provoked violent reactions: the Wars of the Vendée, the “federalist” risings in Normandy and in Provence, the revolts of Lyon and Bordeaux, and the insurrection of the Chouans in Brittany. Opposition, however, was broken by the Reign of Terror (19 Fructidor, year I-9 Thermidor, year II [September 5, 1793-July 27, 1794]), which entailed the arrest of at least 3,00,000 suspects, 17,000 of whom were sentenced to death and executed while more died in prisons or were killed without any form of trial. At the same time, the revolutionary government raised an army of more than one million men.

Thanks to this army, the war entered its fourth phase (beginning in the spring of 1794). A brilliant victory over the Austrians at Fleurus on 8 Messidor, year II (June 26, 1794), enabled the French to reoccupy Belgium. Victory made the Terror and the economic and social restrictions seem pointless. Robespierre, "the Incorruptible," who had sponsored the restrictions, was overthrown in the National Convention on 9 Thermidor, year II (July 27, 1794), and executed the following day (after a failed suicide attempt). Soon after his fall the Maximum was abolished, the social laws were no longer applied, and efforts toward economic equality were abandoned. Reaction set in; the National Convention began to debate a new constitution; and, meanwhile, in the west and in the southeast, a royalist "White Terror" broke out. Royalists even tried to seize power in Paris but were crushed by the young general Napoleon Bonaparte on 13 Vendémiaire, year IV (October 5, 1795). A few days later the National Convention dispersed.

6.1 The Directory and revolutionary expansion

The constitution of the year III, which the National Convention had approved, placed executive power in a Directory of five members and legislative power in two chambers, the Council of Ancients and the Council of the Five Hundred (together called the Corps Législatif). This regime, a bourgeois republic, might have achieved stability had not war perpetuated the struggle between revolutionaries and counterrevolutionaries throughout Europe. The war, moreover, embittered existing antagonisms between the Directory and the legislative councils in France and often gave rise to new ones. These disputes were settled by coups d'état, chiefly those of 18 Fructidor, year V (September 4, 1797), which removed the royalists from the Directory and from the councils, and of 18 Brumaire, year VIII (November 9, 1799), in which Bonaparte abolished the Directory and became the leader of France as its “first consul”.

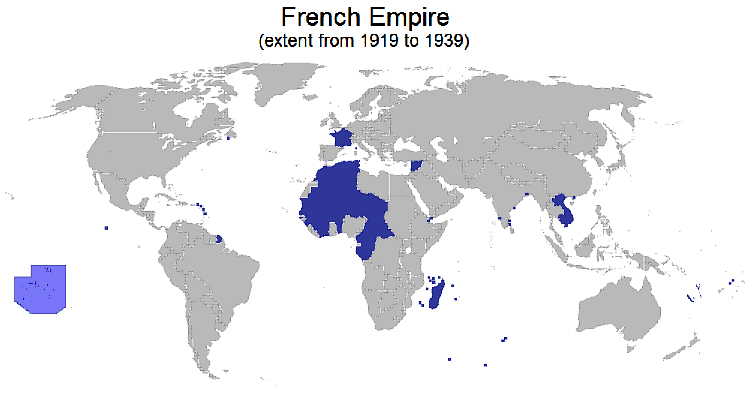

After the victory of Fleurus, the progress of the French armies in Europe had continued. The Rhineland and Holland were occupied, and in 1795 Holland, Tuscany, Prussia, and Spain negotiated for peace. When the French army under Bonaparte entered Italy (1796), Sardinia came quickly to terms. Austria was the last to give in (Treaty of Campo Formio, 1797). Most of the countries occupied by the French were organized as "sister republics," with institutions modeled on those of Revolutionary France.

Peace on the continent of Europe, however, did not end revolutionary expansion. The majority of the directors had inherited the Girondin desire to spread the Revolution over Europe and listened to the appeals of Jacobins abroad. Thus French troops in 1798 and 1799 entered Switzerland, the Papal States, and Naples and set up the Helvetic, Roman, and Parthenopean republics. Great Britain, however, remained at war with France. Unable to effect a landing in England, the Directory, on Bonaparte's request, decided to threaten the British in India by occupying Egypt. An expeditionary corps under Bonaparte easily occupied Malta and Egypt, but the squadron that had convoyed it was destroyed by Horatio Nelson's fleet at the Battle of the Nile on 14 Thermidor, year VI (August 1, 1798). This disaster encouraged the formation of a Second Coalition of powers alarmed by the progress of the Revolution. This coalition of Austria, Russia, Turkey, and Great Britain won great successes during the spring and summer of 1799 and drove back the French armies to the frontiers. Bonaparte thereupon returned to France to exploit his own great prestige and the disrepute into which the military reverses had brought the government. His coup d'état of 18 Brumaire overthrew the Directory and substituted the consulate. Although Bonaparte proclaimed the end of the Revolution, he himself was to spread it in new forms throughout Europe.

7.0 Outcomes of the French Revolution, 1789-1799 (1815)

1. Representative government vs. authoritarianism (the Terror, Napoleon): two different new models of government

2. Stronger, further centralized state with a larger, more effective and more intrusive administration

3. Abolition of special fiscal privileges, seigneurial dues owed by peasants to lords, internal tariffs, and the establishment of uniform tax system based in principle on one's income.

4. Creation and extension of new civil rights:

- equality before the law

- careers open to talent

- participation in elections or certain government positions based on property qualifications

5. Socio-economic changes

a.single commercial code

- abolition of guilds, i.e., workers right to organize in "unions"

- business becomes an honorable profession

- (wealthier) peasants acquire land and more peasants become independent proprietors

- increase in the size and influence of the bourgeoisie, through the acquisition of church lands, greater wealth, and offices as political representatives and government officials

6. Changes in ideas and political culture:

- Liberty, Equality, Fraternity ; popular sovereignty : sovereignty rested with the "people" not in the king, or any narrower group such as the aristocracy; democratic republicanism

- Nationalism

- decline in religiosity, in the influence and authority of the church

- formation of a revolutionary tradition centered on the belief that revolution was a means for bringing progressive change and further extension of popular participation and popular sovereignty.

8.0 Conflicting Interpretations of the Revolution: Causes, nature, outcomes

The Influence of Ideas: "The Revolution had been accomplished in the minds of men long before it was translated into fact." Taylor: Revolutionary ideology was the product, not the cause, of a political and social crisis of revolutionary proportions. A revolutionary situation emerged first and revolutionary thinking came out of that situation.

8.1 The role of the people and violence

1. "This contrast between theory and practice, between good intentions and acts of savage violence, which was the salient feature of the French Revolution, becomes less startling when we remember that the Revolution, though sponsored by the most civilized classes of the nation, was carried out by its least educated and most unruly elements."

Alexis de Tocqueville, The Old Regime and the French Revolution, 1858

2. "The French Revolution gave peoples the sense that history could be changed by their action, and it gave them, incidentally, what remains to this day the single most powerful slogan ever formulated for the politics of democracy and common people which it inaugurated: Liberty, Equality, Fraternity. . . . The French Revolution demonstrated the power of the common people in a manner that no subsequent government has ever allowed itself to forget--if only in the form of untrained, improvised, conscript armies, defeating the conjunction of the finest and most experienced troops of the old regimes. When the common people did intervene in July and August of 1789, they transformed conflict among elites into something quite different, if only by bringing about, within a matter of weeks, the collapse of state power and administration and the power of the rural ruling class in the countryside. This is what gave the Declaration of the Rights of Man a far greater international resonance than the American models that inspired it; what made the innovations of France - including its new political vocabulary - more readily accepted outside; which created its ambiguities and conflicts; and, not least, what turned it into the epic, the terrible, the spectacular, the apocalyptic event which gave it a sort of uniqueness, both horrifying and inspiring."

E.J. Hobsbawm, Echoes of the Marseillaise, 1990

3. The Revolution as a tragedy vs. progressive change:

a. "This great drama [the French Revolution] transformed the whole meaning of political change, and the contemporary world would be inconceivable if it had not happened. . . . In other words it transformed men's outlook. The writers of the Enlightenment, so revered by the intelligentsia who made the Revolution, had always believed it could be done if men dared to seize control of their own destiny. The men of 1789 did so, in a rare moment of courage, altruism, and idealism which took away the breath of educated Europe. What they failed to see, as their inspirers had not foreseen, was that reason and good intentions were not enough by themselves to transform the lot of their fellow men. Mistakes would be made when the accumulated experience of generations was pushed aside as so much routine, prejudice, fanaticism, and superstition. The generation forced to live through the upheavals of the next twenty-six years paid the price. Already by 1802 a million French citizens lay dead; a million more would perish under Napoleon, and untold more abroad. How many millions more still had their lives ruined? Inspiring and ennobling, the prospect of the French Revolution is also moving and appalling: in every sense a tragedy."

William Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution, 1989

b. "The French Revolution was both destructive and creative. It represented an unprecedented effort to break with the past and to forge a new state and new national community based on the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity. After the old government was replaced, differences over the meaning of those principles and the ways they were to be put into practice grew more salient and serious. Thus the revolution continued until a stable state organization was consolidated, in part through the use of military force. Shaped and driven by passionate ideological differences, violence, and war, the revolution bequeathed to the French and to the World a new and enduring political vision: at the heart of progress lay liberation from the past, egalitarianism, and broadly based representative government."

Robert Schwartz

c. The French Revolution was, essentially, the invention of a new political culture: "In my view the social and economic changes brought about by the Revolution were not revolutionary. Nobles were able to return to their titles and to much of their land. Although considerable amounts of land changed hands during the Revolution, the structure of landholding remained much the same; the rich got richer, and the small peasants consolidated their hold, thanks to the abolition of feudal dues. Industrial capitalism grew at a snail's pace. In the realm of politics, in contrast, almost everything changed. Thousands of men and even many women gained firsthand experience in the political arena: they talked, read, and listened in new ways; they voted; they joined new organizations; and they marched for their political goals. Revolution became a tradition, and republicanism an enduring option. Afterward, kings could not rule without assemblies, and noble domination of public affairs only provoked more revolution. As a result, France in the nineteenth century had the most bourgeois polity in Europe, even though France was never the leading industrial power.

Lynn Hunt, Politics, Culture, and Class, 1984

4. A Marxist Interpretation: "After ten years of revolutionary changes and vicissitudes, the structure of French society had undergone a momentous transformation. The aristocracy of the Old Regime had been stripped of its privileges and social preponderance; feudal society had been destroyed. By wiping out every vestige of feudalism, by freeing the peasants from seigneurial dues and ecclesiastical tithes and also to some degree from the constraints imposed by their communities--by abolishing privileged corporations and their monopolies, and by unifying the national market, the French Revolution marked a decisive stage in the transition from feudalism to capitalism."

Albert Soboul, The French Revolution, 1965