Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - being learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

Gandhiji's early career

1.0 Introduction

The third and the last phase of the national movement began in 1919 when the era of popular mass movements was initiated. The two Home Rule Leagues - started by Tilak and Annie Besant - indeed played a major role in seeding this sentiment. The Indian people waged perhaps the greatest mass struggle in modern world history and finally, India's national revolution was victorious.

2.0 GANDHI'S SOUTH AFRICA EXPERIENCE

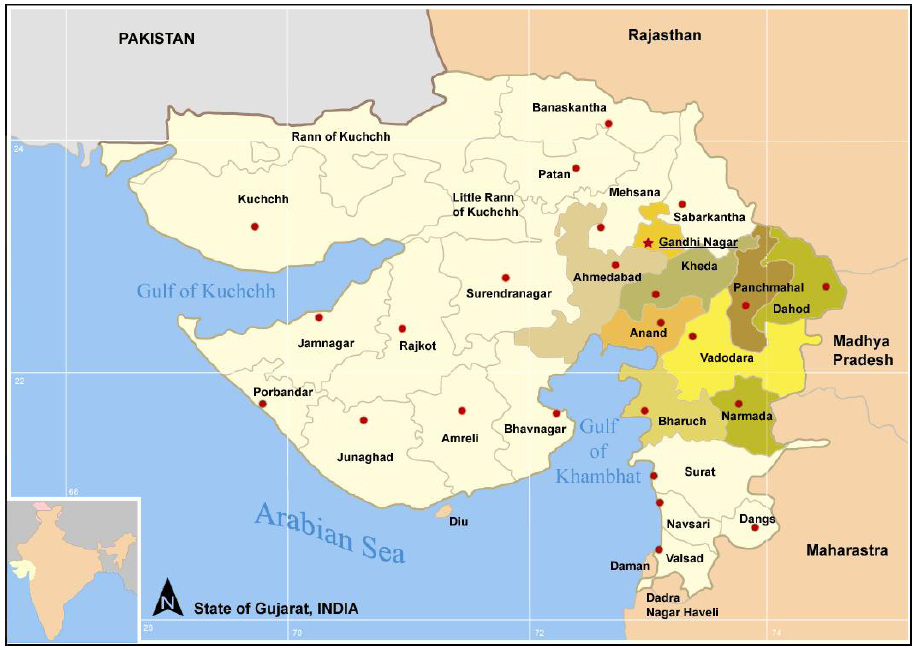

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (M.K.Gandhi) was born on October 2nd, 1869 at Porbandar in Gujarat. After finishing his legal education in Britain, he went to South Africa to practise law on the invitation of an Indian businessman.

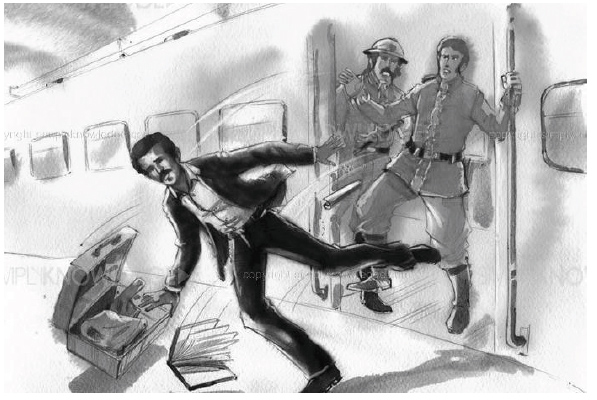

In 1893 he arrived in Durban where he remained for a week before leaving for Pretoria by train. He purchased a first-class ticket, boarded the train and started work on his lawsuit. During the journey a white passenger complained about sharing a compartment with a 'coolie' and Gandhi was asked to move to a third-class carriage. On his refusal he was forcibly removed from the train at Pietermaritzburg Station. Here he spent the night and later he described the event as the most prominent influence on his political future.

Gandhiji's experience in South Africa prepared him for the struggle that was to follow in India. It was here that the weapons of ahimsa and satyagraha were sharpened. During the local and then national struggles in India, Gandhiji often recalled his South African experience as a frame of reference for the direction of the struggles in India. In South Africa, Gandhiji became convinced of the invincibility of non-violent resistance to evil, if properly led. He developed strong convictions on the need for the elimination of untouchability, development of Hindu-Muslim unity, national language, prohibition, respect for manual labour, promotion of spinning and cottage industries etc.

In South Africa, the discrimination and humiliation the Indian populace were subject to by the white rulers could be seen clearly. A year after he arrived in South Africa as a 23 year old barrister, Gandhiji decided to devote himself to serving the Indian community. He established the Natal Indian Congress in 1894 and the Transvaal British Indian Association in 1903. For over a decade, he prepared numerous petitions and memoranda, led deputations to the authorities, wrote letters to the press and tried to promote public understanding and support in South Africa, as well as in India and Britain for the Indian cause.

The Transvaal Asiatic Ordinance of 1906, which required all Indians to register and carry passes eroded Gandhiji's faith in the fairness of the British and in Imperial principles. The Ordinance was denied Royal assent after an Indian deputation (Gandhiji and Haji Ojer Ali) appealed to the Imperial authorities in London. But after self government was granted to Transvaal at the beginning of 1907, it enacted the terms of the Ordinance in the Asiatic Registration Act of 1907.

This led to the first satyagraha in 1907. This initial phase of the campaign ended at the end of January 1908 when General Smuts and Gandhiji reached a provisional settlement under which the Indians would register voluntarily and the Government would repeal the law.

However, in July 1908 the Government reneged on its promise after voluntary registrations had been done and the satyagraha resumed. Over two thousand people, from the small Indian population of less than ten thousand in the Transvaal, as well as some Indians from the Natal, went to prison defying the Registration Act and an immigration law which restricted inter-provincial movement by Indians. The movement was suspended in 1911 during talks with the government of the newly established Union of South Africa.

The Union Government repudiated a promise it made to Gopal Krishna Gokhale, in 1912, to abolish the £3 annual tax which Natal had imposed on indentured labourers who did not re-indenture or return to India at the expiration of their contracts. And in 1913, the Cape Supreme Court declared virtually all Indian marriages invalid, by deciding that only marriages performed under Christian rites and duly registered were valid. The Government ignored appeals by the Indian community for legislation to validate the marriages.

Satyagraha was resumed both in the Transvaal and in Natal with additional demands of abolition of the £3 tax and the validation of marriages.

During this last stage, the movement was joined by workers and women who were directly affected by the £3 tax and the judgment on marriages, and it became a mass movement. People of all religions and occupations

came together in this righteous struggle. Gandhiji and his colleagues were sentenced to long terms of imprisonment. The strikers were rendered leaderless. A notable aspect of this phase of the campaign was the active participation of women. Gandhiji's wife Kasturba who was then in poor health and living on a diet of fruit alone led the way along with several relatives.

Public opinion all over India was aroused. The Viceroy, Lord Hardinge, expressed sympathy with the satyagrahis: the Indian and British Governments intervened and the South African Government was forced to negotiate. The satyagraha ended with the Smuts-Gandhi agreement of June 30, 1914, under which all the demands of the Satyagraha were conceded. The weapon of Satyagraha was soon to be used on a massive scale.)

2.1 The Power of Satyagraha

Gandhi soon became the leader of the struggle against these conditions and during 1893-1914 was engaged in a heroic though unequal struggle against the racist authorities of South Africa. It was during this long struggle lasting nearly two decades that he evolved the technique of satyagraha based on truth and non-violence. The ideal satyagrahi was to be truthful and perfectly peaceful, but at the same time he would refuse to submit to what he considered wrong. He would accept suffering willingly in the course of struggle against the wrong-doer. This struggle was to be part of his love of truth. But even while resisting evil, he would love the evil-doer. Hatred would be alien to the nature of a true satyagrahi. He would, moreover, be utterly fearless.

He would never bow down before evil whatever the consequences. In Gandhi's eyes, non-violence was not a weapon of the weak and the cowardly. Only the strong and the brave could practise it.

An important aspect of Gandhi's outlook was that he would not separate thought and practice, belief and action. His truth and non-violence were meant for daily living and not merely for high-sounding speeches and writings. He also had immense faith in the capacity of the common people to fight.

3.0 GANDHI'S RETURN TO INDIA IN 1915

Gandhiji returned to India in 1915 at the age of 46 and almost immediately was called upon to join the Congress. But he decided that it was important for him to understand the country first. For this he spent an entire year travelling all over India. In 1916, he founded the Sabarmati Ashram at Ahmedabad where his friends and followers were to learn and practise the ideas of truth and non-violence. He also set out to experiment with his new method of struggle.

3.1 The 1917 Champaran Satyagraha

Gandhi's Indian experiment began in 1917 in Champaran, a district in Bihar. The peasants on the indigo plantations in the district were compelled to grow indigo on at least 3/20th of their land by the European planters and to sell it at prices fixed by them, which were very low as compared to market price. Similar conditions had prevailed earlier in Bengal, but as a result of the indigo uprising during 1859-'61 the peasants there had won their freedom from the indigo planters.

Having heard of Gandhi's campaigns in South Africa, several peasants of Champaran invited him to come and help them. Accompanied by Babu Rajendra Prasad, Mazhar-ul-Huq, J.B. Kripalani, Narhari Parekh and Mahadev Desai, Gandhiji reached Champaran in April 1917 and began to conduct a detailed inquiry into the condition of the peasantry. The infuriated district officials ordered him to leave Champaran, but he defied the order and was willing to face trial and imprisonment. This forced the government to cancel its earlier order and to appoint a committee of inquiry on which Gandhiji served as a member.

(However, aggravated by Gandhi's popularity and the way he stirred up the peasants, the European planters began a "poisonous agitation" against Gandhi, where they spread false reports and rumors about Gandhi and his co-workers. Gandhi sent information to the newspapers, but they were never published.

By June 12, Gandhi and his co-workers had recorded over 8,000 statements, and began to compile an official report. They also held several meetings with planters and peasants in various places such as Bettiah and Motihari. The gatherings were somewhere between 10,000 and 30,000 people. On October 3, they submitted a unanimous report favouring the peasants to the Government. On October 18, the Government published its resolution, essentially accepting almost all of the report's recommendations. On November 2, Mr. Maude introduced the Champaran Agrarian Bill that was passed and became the Champaran Agrarian Law (Bihar and Orissa Act I of 1918). The government accepted the laws in March of 1918.)

3.2 The 1918 Ahmedabad Mill Strike

In 1918, Mahatma Gandhi intervened in a dispute between the workers and mill-owners of Ahmedabad. In February-March 1918, there was a dispute between the mill owners and workers over the issue of Plague Bonus of 1917. The Mill owners wanted to withdraw the bonus whereas the workers were demanding a 50% hike in wages. The mill owners were ready to give only a 20% bonus. He advised the workers to go on strike and to demand a 35 percent increase in wages. But he insisted that the workers should not use violence against the employers during the strike. He undertook a fast unto death to strengthen the workers' resolve to continue the strike. But his fast also put pressure on the mill-owners who relented on the fourth day and agreed to give the workers a 35 per cent increase in wages.

3.3 The 1918 Kheda Satyagraha

(In Kheda district of Gujarat, the peasants mostly owned their own lands, and were economically better-off than their compatriots in Bihar. However, the district was plagued by poverty, scant resources, the social evils of alcoholism and untouchability, and overall British indifference and hegemony. A terrible famine struck the district and a large part of Gujarat, and had virtually destroyed the agrarian economy. The poor peasants had barely enough to feed themselves, but the British government of the Bombay Presidency insisted that the farmers not only pay full taxes, but also pay the 23% increase stated to take effect that very year. The district also saw crop failure in 1918.

Though civil groups were sending petitions and editorials were being published against the exorbitant taxes, no effect was seen on the British. Gandhi proposed satyagraha - non-violence, mass civil disobedience. While it was strictly non-violent, Gandhi was proposing real action, a real revolt that the oppressed peoples of India were dying to undertake. Gandhi also insisted that neither the protestors in Bihar nor in Gujarat allude to or try to propagate the concept of Swaraj, or Independence. This was not about political freedom, but a revolt against abject tyranny amidst a terrible humanitarian disaster. While accepting participants and help from other parts of India, Gandhi insisted that no other district or province revolt against the Government, and that the Indian National Congress not get involved apart from issuing resolutions of support, to prevent the British from giving it cause to use extensive suppressive measures and brand the revolts as treason.)

3.4 Gandhiji's evolution as a leader

These experiences brought Gandhiji in close contact with the masses whose interests he actively espoused all his life. In fact, he was the first Indian nationalist leader who identified his life and his manner of living with the life of the common people. In time he became the symbol of poor India, nationalist India, and the Indian freedom movement. Other causes very dear to Gandhi's heart were Hindu-Muslim unity, the fight against untouchability and the elevation of the status of women in the country. He once summed up his aims as follows:

"I shall work for an India in which the poorest shall feel that it is their country, in whose making they have an effective voice, an India in which there shall be no high class and low class of people, an India in which all communities shall live in perfect harmony ...There can be no room in such an India for the curse of untouchabitity ...Women will enjoy the same rights as men ...This is the India of my dreams."

Though a devout Hindu, Gandhi's cultural and religious outlook was universalist and not narrow. "Indian culture", he wrote, "is neither Hindu, Islamic, nor any other, wholly. It is a fusion of all". He wanted Indians to have deep roots in their own culture but at the same time to acquire the best that other world cultures had to offer. He said:

"I want the culture of all lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet by any. I refuse to live in other people's houses as an interloper, a beggar or a slave."

3.5 The 1919 Satyagraha Against the Rowlatt Act

In 1919 a new Act was passed by the British government to give themselves greater power over the people of India. This Act was called the Rowlatt Act and was named after the Rowlatt Commission which had sent recommendations to the Imperial Legislative Council. The Act was also known as the "Black Act" or "Black Bill" by the Indians who protested it. This law was strongly opposed by the people of India because it gave the British government even more authority over them. This new Act allowed the British to arrest and imprison anyone without a trial if they were thought to be plotting against the British. The Viceroy also had the power to silence the press with this new Act.

Along with other nationalists, Gandhiji was also opposed to the Rowlatt Act. In February 1919, he founded the Satyagraha Sabha whose members took a pledge to disobey the Act and court arrest and imprisonment. This was a new method of struggle. The nationalist movement till date, whether under moderate or extremist leaderships, had confined its struggle to agitation. Big meetings and demonstrations, refusal to cooperate with the government, boycott of foreign cloth and schools, or individual acts of terrorism were the only forms of political work known to the nationalists. Satyagraha immediately raised the movement to a new, higher level. Nationalists could now act, instead of merely agitating and giving only verbal expression to their dissatisfaction and anger.

This was the beginning of bringing the masses of peasants, artisans and the urban poor into the Indian struggle against the British. Gandhiji asked the nationalist workers to go to the villages. He increasingly turned the face of nationalism towards the common man and the symbol of this transformation was to be khadi, or hand-spun and handwoven cloth, which soon became the uniform of the nationalists. He spun daily to emphasise the dignity of labour and the value of self-reliance. India's salvation would come, he said, when the masses were wakened from their sleep and became active in politics. The people responded magnificently to Gandhi's call.

March and April 1919 witnessed a remarkable political awakening in India. Almost the entire country came to life. There were hartals, strikes, processions and demonstrations. The slogans of Hindu-Muslim unity filled the air. The entire country was electrified with a sense of patriotism and positivity. The Indian people were no longer willing to submit to the degradation of foreign rule.

3.6 The 1919 Jallianwala Bagh Massacre

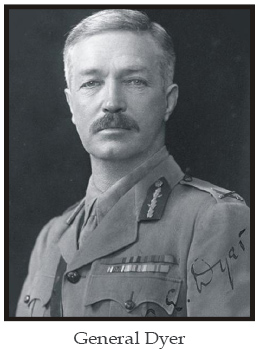

Fearful of the rise of a new pan-India agitation, the British Indian government was determined to suppress the mass agitation against the Rowlatt Act. In a display of cowardice and barbarism, it repeatedly lathi-charged and fired upon unarmed demonstrators in Bombay, Ahmedabad, Calcutta, Delhi and also in other cities. Gandhiji gave a call for a mighty hartal on 06th April 1919. The people responded with unprecedented enthusiasm. The government decided to meet the popular protest with repression, particularly in the Punjab. A large but unarmed crowd had gathered on 13 April 1919 at Amritsar (Punjab) in Jallianwala Bagh, to protest against the arrest of their popular leaders, Dr.Saifuddin Kitchlew and

Dr. Satyapal. General Dyer, the military commander of Amritsar, decided to terrorise the people of Amritsar into complete submission. Jallianwala Bagh was a large open space which was enclosed on three sides by buildings and had only one exit. He surrounded the Bagh (garden) with his army unit, closed the exit with his troops, and then ordered his men to shoot into the trapped crowd with rifles and machine-guns. They fired till their ammunition was exhausted. Thousands were killed and wounded. After this massacre, martial law was proclaimed throughout Punjab and the people had to face the most brutal atrocities. This was just one of the incidents that created a reign of terror in Punjab. A wave of horror ran through the country as the knowledge of the Punjab happenings spread. People saw as if in a flash the ugliness and brutality that lay behind the facade of civilisation that imperialism and foreign rule professed. The people of India, for the first time, saw the naked ambition of the British, which completely exposed their shamelessness and brutality.

Popular shock was expressed by the great poet and humanist Rabindranath Tagore who renounced his knighthood in protest and declared:

"The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in their incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part wish to stand shorn of all special distinctions, by the side of my countrymen who, for their so-called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings."

India and the Indian people had entered the final phase of the freedom struggle. The British, after centuries of oppression and exploitation, were to get a taste of Gandhi's remedial medicine, which was to lead to their final expulsion from the subcontinent, two decades later.