Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - being learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

The INA trials and the RIN Revolt

1.0 Introduction

The end of World War II marked a dramatic change. India’s struggle for freedom entered a new phase. The Revolt of 1942 and the INA had revealed the heroism and determination of the Indian people. Many local and regional struggles like the Tebhaga Movement

(a militant campaign initiated in Bengal by the Kisan Sabha - the peasants front of Communist Party of India) in 1946, the Warlis Revolt (by Warli tribe, an indigenous tribe living in mountainous as well as coastal areas of Maharashtra-Gujarat border), the Punjab kisan morchas, the Travancore people’s struggle (especially the Punnapra-Vayalar episode) and the Telangana Movement had an anti-imperialist edge.

When Congress leaders emerged from jail in mid-June 1945, they were surprised to find tumultuous crowds waiting for them, impatient to do something, restless and determinedly anti-British. Repression had steeled the brave and stirred the conscience of the fence-sitter. Political energies were surfacing after more than three years of repression and the expectations of the people were now heightened by the release of their leaders. With the release of the national leaders from jail, the people began to look forward to another, perhaps the final, struggle for freedom.

2.0 The Changed British Attitude

Elections in Britain had unexpectedly led the Labour Party to power. Clement Attlee, the new Prime Minister was in a hurry to settle the Indian problem. Several reasons are attributed to this change in attitude.

Firstly, the war had changed the balance of power in the world. Not Britain, but the United States of America and the Soviet Union emerged from the war as the big powers. Both supported Indian’s demand for freedom. This weakened the British resolve to continue in India.

Secondly, even though Britain was on the winning side in the war, its economic and military power was shattered. It would take Britain years to rehabilitate itself. And the change of government in Britain with the Conservatives replaced by the Labour Party, the Congress demands got unexpected support. The British soldiers were weary of war. Having fought and shed their blood for nearly six years, they had no desire to spend many more years away from home in India suppressing the Indian people’s struggle for freedom.

Thirdly, the British Indian Government could not any longer rely on the Indian personnel of its civil administration and armed forces to suppress the national movement. The INA had shown that patriotic ideas had entered the ranks of the professional Indian army, the chief instrument of British rule in India. Another straw in the wind was the famous revolt of the Indian naval ratings at Bombay in February 1946. The ratings had fought a seven-hour battle with the army and navy and had surrendered only when asked to do so by the national leaders. Naval ratings in many other parts had gone on sympathetic strike. Moreover, there were also widespread strikes in the Royal Indian Air Force.

The Indian Signal Corps at Jabalpur also went on strike. The other two major instruments of British rule, the police and the bureaucracy, were also showing signs of nationalist leanings. They could no longer be safely used to suppress the national movement. For example, the police force in Bihar and Delhi went on strike.

Fourthly, and above all, the confident and determined mood of the Indian people was by now obvious. They would no longer tolerate the humiliation of foreign rule. They would no longer rest till freedom was won.

3.0 The INA Trials

After World War Two, the British captured some 23, 000 INA soldiers and charged them with treason. In November 1945, the INA trials began at the Red Fort. SN Khan, PK Sahgal and GS Dhillon, the first three senior INA officers became symbols of India fighting for her independence. Protests against the trials took place in February and March 1946.

3.1.1 The first trial

The first trial was held between November and December 1945. The charges against the three accused were:

Against Gurubaksh Singh Dhillon

- Waging War against the King contrary to the section 121 of the Indian Penal Code.

- Four charges of murder contrary to the Section 302 of the Indian Penal code.

Against Prem Sahgal

- Waging War against the King contrary to the section 121 of the Indian Penal Code.

- Four charges of abetment to murder in the charges brought contrary to Section 109 of the Indian Penal Code.

Against Shah Nawaz

- Waging War against the King contrary to the section 121 of the Indian Penal Code.

- One charge of abetment of murder in the charges brought contrary to Section 109 of the Indian Penal Code.

- The charge of Waging War consisted of planning, organisation and participation in military operations between September 1942 and April 1945.

- The murder and abetment charges concerned the shooting of INA members for desertion and attempting to communicate with the enemy in the Popa Hill area of Burma.

3.1.2 Second trial

These were the trials of Abdul Rashid, Shinghara Singh, and Fateh Khan. In light of unrest over the charges of treason and glorification in the first trial, the charges of treason were dropped. The site of trial was also moved from the Red Fort to an adjoining building.

An announcement by the Government, limiting trials of the INA personnel to those guilty of brutality or active complicity, was due to be made by the end of August 1945. However, before this statement could be issued, Nehru raised the demand for leniency at a meeting in Srinagar on 16th August 1945. The defence of the INA prisoners was taken up by the Congress and Bhulabhai Desai, Tej Bahadur Sapru, K.N. Katju, Nehru and Asaf Ali appeared in court at the historic Red Fort trials. The Congress organized an INA relief and enquiry committee, which provided small sums of money and food to the men on their release, and attempted to secure employment for them.

The INA agitation was a landmark. The high pitch or intensity at which the campaign for the release of INA prisoners was conducted was unprecedented. This was evident from the press coverage and other publicity it got, from the threats of revenge that were publicly made and also from the large number of meetings held.

Initially, the appeals in the press were for clemency to ‘misguided’ men, but by November 1945, when the first Red Fort trials began, there were daily editorials hailing the INA men as the most heroic patriots and criticizing the Government stand. Priority coverage was given to the INA trials and to the INA campaign, eclipsing international news. Pamphlets, the most popular one being ‘Patriots Not Traitors’, were widely circulated, ‘Jai Hind’’ and ‘Quit India’ were scrawled on walls of buildings in Ajmer. Posters threatening death to ‘20 English dogs for every INA man sentenced’’, were pasted all over Delhi. In Benaras, it was declared at a public gathering that ‘if INA men were not saved, revenge would be taken on European children.’ One hundred and sixty political meetings were held in the Central Provinces and Berar alone in the first fortnight of October 1945 where the demand for clemency for INA prisoners was raised. INA Day was observed on 12 November and INA Week from 5 to 11 November 1945. While 50,000 people would turn out for the larger meetings, the largest meeting was the one held in Deshapriya Park Calcutta. Organized by the INA Relief Committee, it was addressed by Sarat Bose, Nehru and Patel. Estimates of attendance ranged from two to three lakhs to Nehru’s five to seven lakhs.

Another significant feature of this phase was its wide geographical reach and the participation of diverse social groups and political parties. This had two aspects. One was the generally extensive nature of the agitation, the other was the spread of pro-INA sentiment to social groups hitherto outside the nationalist pale. The Director of the Intelligence Bureau coceded: ‘There has seldom been a matter which has attracted so much Indian public interest, and it is safe to say, sympathy’. Nehru confirmed the same: ‘Never before in Indian history had such unified sentiments and feelings been manifested by various divergent sections of the Indian population as it had been done with regard to the question of the Azad Hind Fauj’.

While the cities of Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta and Madras and the towns of U.P. and Punjab were the nerve centres of the agitation, what was more noteworthy was the spreading of the agitation to places as distant as Coorg, Baluchistan and Assam.

Municipal Committees, Indians abroad and Gurudwara Committees subscribed liberally to the INA funds. The Shiromani Gurudwara Prabhandhak Committee, Amritsar donated Rs. 7,000 and set aide another Rs. 10,000 for relief. Diwali was not celebrated in some areas of Punjab in sympathy with the INA men. Calcutta Gurudwaras became the campaign center for the INA cause. The Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh (RSS), the Hindu Mahasabha and the Sikh League supported the INA cause.

Participation was of many kinds — some contributed funds, others attended or organized meetings, shopkeepers downed shutters and political parties and organizations raised the demand for the release of the prisoners. Municipal Committees, Indians abroad and Gurdwara committees subscribed liberally to INA funds. The Poona City Municipality, the Kanpur City Fund and a local district board in Madras Presidency contributed Rs 1,000 each. More newsworthy contributions were those by film stars in Bombay and Calcutta, by the Cambridge Majlis and the tongawallas of Amraoti. Students, whose role in the campaign was outstanding, held meetings and rallies and boycotted classes from Salem in the south to Rawalpindi in the north. Commercial institutions, shops and markets stopped business on the day the first trial began, 5 November 1945, on INA Day and during INA Week.

Demands for release were raised at Kisan Conferences in Dhamangaon and Sholapur on 16 November 1945 and at the tenth session of the All India Women’s Conference in Hyderabad on 29 December 1945. ‘Even English intellectuals, birds of a year or two’s sojourn in India, were taking a keen interest in the rights and wrongs, and the degrees of wrong, of the INA men,’ according to General Tuker of the Eastern Command. Diwali was not celebrated in some areas in sympathy with the INA men. Calcutta Gurdwaras became a campaigning centre for the INA cause. The Muslim League, the Communist Party of India, the Unionist Party, the Akalis, the Justice Party, the Abrars in Rawalpindi, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, the Hindu Mahasabha and the Sikh League supported the INA cause in varying degrees. The Viceroy noted that ‘all parties have taken the same line though Congress seems more vociferous than the others’.

The response of the armed forces was unexpectedly sympathetic, belying the official perception that loyal soldiers were very hostile to the INA ‘traitors’. Royal Indian Air Force (RIAF) men in Kohat attended Shah Nawaz’s meetings and army men in UP and Punjab attended INA meetings, often in uniform. RIAF men in Calcutta, Kohat, Allahabad, Bamrauli and Kanpur contributed money for the INA defence, as did other service personnel in U.P. Apart from these instances of overt support, a ‘growing feeling of sympathy for the INA pervaded the Indian army’, according to the Commander-in-Chief. He concluded that the ‘general opinion in the Army is in favour of leniency’ and recommended to Whitehall that leniency be shown by the Government.

Interestingly, the question of the right or wrong of the INA men’s action was never debated. What was in question was the right of Britain to decide a matter concerning Indians. As Nehru often stressed, if the British were sincere in their declaration that Indo-British relations were to be transformed, they should demonstrate their good faith by leaving it to Indians to decide the INA issue. Even the appeals by liberal Indians were made in the interest of good future relations between India and Britain. The British realised this political significance of the INA issue. The Governor of North-West Frontier Province advocated that the trials be abandoned, on the ground that with each day the issue became ‘more and more purely Indian versus British.’

4.0 The RIN revolt (ROYAL INDIAN NAVY REVOLT)

The RIN revolt started on 18 February when 1100 naval ratings of HMS Talwar struck work at Bombay to protest against the treatment meted out to them which included flagrant racial discrimination, unpalatable food and abuses to boot. B.C. Dutt, a rating, was arrested for scrawling ‘Quit India’ on the HMIS Talwar. This was sorely resented. The next day on a rumour that ratings had been fired upon, ratings from Castle and Fort Barracks joined the strike. They left their posts and went around Bombay in lorries, holding aloft Congress flags, threatening Europeans and policemen and occasionally tweaking a shop window or two.

The second stage of these upsurges, when people in the city joined in, was marked by a virulent anti-British mood and resulted in the virtual paralysis of the two great cities of Calcutta and Bombay. Meetings and processions to express sympathy, as also strikes and hartals, were quickly overshadowed by the barricades that came up. Pitched battles were fought from housetops and by-lanes. The attacks on Europeans, and the burning of police stations, post offices, shops, tram depots, railway stations, banks, grain shops became a regular occurrence. These incidences in Bombay alone accounted for, according to official estimates, the destruction of thirty shops, ten post offices, ten police chowkis, sixty-four food grains shops and 200 street lamps. Normal life in the city was completely disrupted. The Communist call for a general strike brought lakhs of workers out of their factories into the streets. Hartals by shopkeepers, merchants and hotel-owners and strikes by student workers, both in industry and public transport services almost brought the whole city to a grinding halt. Forcible stopping of trains by squatting on rail-tracks, stoning and burning of police and military lorries and barricading of streets did the rest.

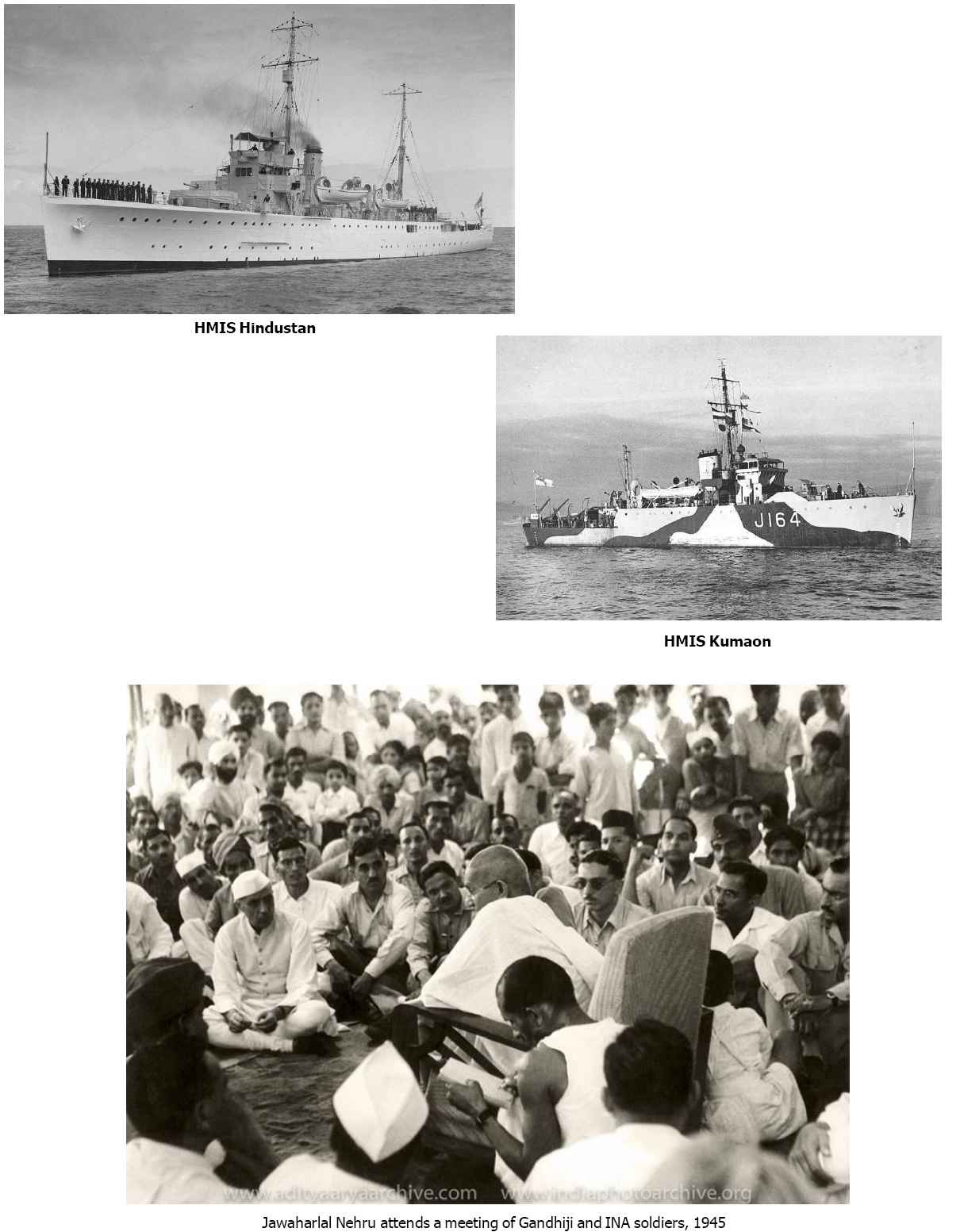

The third phase was characterized by a display of solidarity by people in other parts of the country. Students boycotted classes, hartals and processions were organized to express sympathy with the students and ratings and to condemn official repression. In the RIN revolt, Karachi was a major centre, second only to Bombay. The news reached Karachi on 19 February, upon which the HMIS Hindustan along with one more ship and three shore establishments, went on a lightning strike. Sympathetic token strikes took place in military establishments in Madras, Vishakhapatnam, Calcutta, Delhi, Cochin, Jamnagar, the Andamans, Bahrain and Aden. Seventy eight ships and 20 shore establishments, involving 20,000 ratings, were affected. Men went on sympathetic strikes in the Marine Drive, Andheri and Sion areas of Bombay and in Poona, Calcutta, Jessore and Ambala units. Sepoys at Jabalpur went on strike while the Colaba cantonment showed ominous ‘restlessness’.

5.0 Significance of the INA Trials and the RIN Revolt

There is no doubt that these three upsurges were significant in as much as they gave expression to the militancy in the popular mind. Action, however reckless, was fearless and the crowds which faced police firing by temporarily retreating, only to return to their posts, won the Bengal Governor’s grudging admiration! The RIN revolt remains a legend to this day. When it took place, it had a dramatic impact on popular consciousness. A revolt in the armed forces, even if soon suppressed, had a great liberating effect on the minds of people. The RIN revolt was seen as an event which is seen by some as the event which marked the end of British rule almost as finally as Independence Day, 1947.

Some historians are of the view that the three upsurges were an extension of the earlier nationalist activity with which the Congress was integrally associated. It was the strong anti-imperialist sentiment fostered by the Congress through its election campaign, its advocacy of the INA cause and its highlighting of the excesses of 1942 that found expression in the three upsurges that took place between November 1945 and February 1946. The Home Department’s provincial level enquiry into the causes of these ‘disturbances’ came to the conclusion that they were the outcome of the ‘inflammatory atmosphere created by the intemperate speeches of Congress leaders in the last three months.’ The Viceroy had no doubt that the primary cause of the RIN ‘mutiny’ was the ‘speeches of Congress leaders since September last.’ In fact, the Punjab CID authorities warned the Director of the Intelligence Bureau of the ‘considerable danger,’ while dealing with the Communists, ‘of putting the cart before the horse and of failing to recognize Congress as the main enemy’.

These three upsurges were distinguishable from the activity preceding them because the form of articulation of protest was different. They took the form of a violent, flagrant challenge to authority. The earlier activity was a peaceful demonstration of nationalist solidarity. One was an explosion, the other a groundswell.

Reflecting on the factors that guided the British decision to relinquish the Raj in India, Clement Attlee, the then British prime minister, cited several reasons, the most important of which were the INA activities of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, which weakened the Indian Army - the foundation of the British Empire in India - and the RIN Mutiny that made the British realise that the Indian armed forces could no longer be trusted to prop up the Raj. Although Britain had made, at the time of the Cripps’ mission in 1942, a commitment to grant dominion status to India after the war, these developments suggest that, contrary to the usual narrative of India’s independence struggle which generally focuses on Congress and Mahatma Gandhi, the INA and the revolts, mutinies, and public resentment it germinated were an important factor in the complete withdrawal of the Raj from India.

Leading individuals in Indian Independence movement in 1920s, 30s and 40s

- About : Indian freedom fighter Bhulabhai Desai is best remembered for his contribution in the field of law. He was one of the most eminent lawyers of British India. His capabilities as a lawyer were realized when defended three soldiers of the Indian National Army in court, who had been accused of treason to India during the World War II. However, his career in politics was tainted when his secret agreement with Muslim League leader, Liaquat Ali Khan was leaked only to show him in a bad light. The association with Liaquat Ali Khan not only lost him the support of other leaders in the Indian National Congress, it also spelt doom in his political career. However, it was always India's wellbeing that Bhulabhai Desai had in mind and it was towards the freedom of India that his entire life was dedicated to.

- Adolescence & Education : Bhulabhai Desai was born on October 13, 1877 in the city of Valsad in Gujarat. His initial years of schooling started at home in Valsad. It was only in the secondary years that he was sent for studies at the Avabai School in Valsad and later to the Bharada High School in Bombay, from where he completed his matriculation, with the highest marks in the batch of 1895. After school, Bhulabhai Desai enrolled at the Elphinstone College in Bombay with English Literature and History as his major subjects of study. He not only graduated successfully with English Literature and History, but also secured the highest score in History and Political Economy. Bhulabhai Desai was awarded the Wordsworth Prize and a scholarship for his outstanding performance by authorities of Elphinstone College. Bhulabhai Desai then went on to complete his M.A. in English from the University of Bombay.

- Career in Academics : After competing his studies from the University of Bombay, Bhulabhai Desai returned to Gujarat to join as a professor of English and History in the Gujarat College, located in Ahmedabad. While he was a teacher, Bhulabhai Desai spent his free time studying law. After the completion of studies in law, Bhulabhai Desai quit his position at the Gujarat College to join as an advocate at the Bombay High Court in the year 1905. Bhulabhai Desai went on to become one of the most celebrated lawyers of Bombay city and India as a whole.

- Career in Politics : Bhulabhai Desai's first plunge in politics was with Annie Besant's political organization the All India Home Rule League. Bhulabhai Desai had also been part of the Indian Liberal Party, but left his position soon after he realized that the Simon Commission, formed in 1928, was in support of the Europeans, especially the British. The Indian Liberal Party too was largely influenced by the British. From the year 1928, Bhulabhai Desai became involved with the activities of the Indian National Congress, after he played an integral role in the Bardoli Satyagraha of 1928, representing the farmers of the region. But it was two years later, in the year 1930, that Bhulabhai Desai became a member of the Congress party. In the year 1932, Bhulabhai Desai was arrested and sent to jail, with the British accusing that the Swadeshi Sabha formed under the leadership of Bhulabhai Desai was functioning illegally in the country. Upon release from jail, he was sent to Europe due to health concerns. It was on the insistence of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the leader of the Bardoli Satyagraha, that Bhulabhai Desai was included in the Congress Working Committee. In the year 1934, Bhulabhai Desai got elected to the Central Legislative Assembly from Gujarat. After the passing of the Government of India Act 1935, there was a debate as to whether the Congress should participate in the legislature since provincial autonomy was being exercised. It was Bhulabhai Desai who initiated talks of Congress' participation, therefore, when Congress entered the Central Assembly, he was elected as the leader of Congressmen. Later, when the British government in India insisted upon India's participation in World War II, it was Bhulabhai Desai who made it clear that India would not support a war where the country's interests were not served. He participated in the satyagraha initiated by Gandhi, but was arrested on December 10, 1940, under the Defense of India Act and sent to Yeravada jail. He was released in September 1941 due to poor health.

- Desai - Liaquat Pact : Bhulabhai Desai was one of the Congressmen who were not in jail during the Quit India Movement of 1942 - 1945, with all important leaders behind bars. It was at this time that Desai came in touch with Muslim League leader Liaquat Ali Khan, both fighting for the release of the political leaders arrested during the Quit India Movement. Talks between the two progressed to form a coalition government consisting of Hindus and Muslims, so that both sects could work for the country after independence.

- In his talks with Bhulabhai Desai, Liaquat Ali Khan said that the Muslim League would drop their demands of a separate state for Muslims, if they were given equal representation in the coalition government. Bhulabhai Desai was also of the opinion that this agreement would mean a quick end to the Quit India Movement, a faster process for India's freedom and the release of important Congress leaders. However, both Bhulabhai Desai and Liaquat Ali Khan had kept their pact a secret from important leaders like Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru of the Congress and Mohammad Ali Jinnah of the Muslim League. And this was what led to the fallout of the plan.

- When the press became aware of the secret pact entered into by Bhulabhai Desai and Liaquat Ali Khan in the year 1945, reports were made public thus alarming both parties. While Bhulabhai Desai agreed that he had participated in the pact, Liaquat Ali Khan clearly denied any association. This led not only to the failure of the Desai - Liaquat Pact, but also to the end of the road to Bhulabhai Desai's political career. He lost the support of all Congress leaders and was not allowed to contest elections from the Constituent Assembly of India. This entire theory was challenged by eminent people like Sir Chiman Lal Setalwad who have stated that Gandhi had full knowledge of the ongoing negotiations. It was their intention to negotiate an agreement for a future coalition government, which would enable a united choice for Hindus and Muslims for the independent Government of India.

- INA Soldiers Judgment : Bhulabhai Desai's most important and most reported incident as a lawyer came in the year 1945 during the INA Soldiers trial. Three Indian National Army officers Shahnawaz Khan, Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon and Prem Kumar Sahgal were accused of treason against the country during the World War II. Bhulabhai Desai was part of the 17 member defense team of the three INA soldiers. The trial began in October 1945 at Red Fort in Delhi. In spite of the fact that Bhulabhai Desai was ill, his arguments in court, for a period of three months, were passionately delivered. Bhulabhai Desai argued on behalf of the soldiers, keeping in mind the concept of international law and the order of provisional government. The three officers were however pronounced guilty after the hearing and were sentenced to transportation for life. The 1945 case was the most important one in the legal career of Bhulabhai Desai.

- Personal Life : Bhulabhai Desai was married to a girl named Ichchhabhen when both were mere schoolchildren and the couple also had a son shortly after marriage, whom they named Dhirubhai. Ichchhabhen lost her life to cancer in the year 1923.

- Death : Bhulabhai Desai died on May 6, 1946. The Bhulabhai Memorial Institute stands in Mumbai, commemorating the contribution of Bhulabhai Desai towards the country. Writer M C Setalwad penned 'Bhulabhai Desai Road', the biography of the eminent politician, lawyer and freedom fighter after his death.

Leading individuals in Indian Independence movement in 1920s, 30s and 40s

- Early years : Born Lakshmi Swaminathan, christened Captain Lakshmi by Subhash Chandra Bose, Laksmi Sahgal’s name stands etched in the annals of Indian history. Her father was S.Swaminathan, a practicing criminal lawyer, and mother A.V.Ammakutty, a social worker and independent activist, from Palghat, Kerala. Choosing to study medicine, she received her medical degree M.B.B.S. in 1938. After a year she received her Diploma in Gynaecology and Obstetrics and worked in the Govt. Kasturba Gandhi Hospital in Chennai as a doctor.

- Marriage : She had a brief marriage to pilot P.K.N.Rao. When the marriage did not succeed, she went to Singapore. During that time Subhash Chandra Bose and his Azad Hind Fauj or Indian National Army was active there. Meeting some of his followers, she came to know about the role of the INA in India’s freedom struggle. She was already working for the health of migrant women labourers, who were mostly Indian and that was when she also became part of the India Independence League.

- British surrender to Japanese : During the surrender of the British to the Japanese in the Second World War, Sahgal was aiding many prisoners of war, and many sought to form an Indian Independence Army that would help free India from the British who were ruling. Subhash Chandra Bose arrived in Singapore in July 1943. In his public speeches he emphasized the role that women could play in the fight for India’s independence and showed a keenness to form a women’s regiment that would work shoulder to shoulder with the men.

- Rani of Jhansi regiment : Lakshmi Sahgal was a firebrand even as a young girl in Chennai when she took part in picketing against liquor trade and the sale of foreign goods in India, and had even burned her foreign material dresses, books, toys etc. When she met Subhash Chandra Bose and proposed an all-women regiment called Rani of Jhansi regiment it was readily accepted. She became Captain Lakshmi with many enthusiastic women under her. Things took a turn in the ongoing World War and while the Japanese got bombed, the INA as being part of it had many of its personnel arrested, of which Lakshmi was one. Arrested in Burma in 1945, she was sent to India in 1946. She was later freed.

- 1947 : There was a huge influx of refugees in 1947 and she literally sank her teeth into her job by working day and night for the poor. Her major concern was serving the poor especially women and her compassion for them became legendary. Her many years passed in such selfless service that she carried on tirelessly, without seeking reward or recognition. She even started a maternity home for the poor that remains till this day.

- Many other movements : After India became independent in 1947, Lakshmi Sahgal continued her political journey in Free India. In 1971, she joined the Communist party of India Marxist (CPI(M)) and represented it in the Rajya Sabha. the Bangladesh war saw many refugees come into India. As leader of the All India Democratic Women’s Association that she founded in ’81, she and her team campaigned and led many activities for these migrant women and many other causes. Helping the Bhopal Gas tragedy victims in 1984, working for restoring peace in Kanpur following the anti-Sikh riots of 1984, came naturally to her. Her visits to her clinic at Kanpur continued all the while and till 2006 when she was 92, she made it a regular habit in her life.

- Awarded : In 1998, Sahgal was awarded the Padma Vibhushan by Indian president K. R. Narayanan. She had the honor of being chosen by the Left parties in 2002 to compete against Dr.Kalam who was the favoured one for President. She had married Prem Kumar Sahgal in March 1947 and settled in Kanpur. Her medical practice continued as before especially with the influx of refugees into India following the Partition. She has two daughters Subhashini Ali and Anisa Puri. Subhashini is a prominent Communist politician and labour activist.

- Early years : Tej Bahadur Sapru was born in Aligarh into an aristocratic Kashmiri Brahmin family living in Delhi. He attended high school in Aligarh and matriculated at Agra College, where he took his law degree. After an apprenticeship at Moradabad he joined the Allahabad High Court in 1898. He was knighted in 1923 for outstanding legal contributions. He set impeccable standards in his personal and professional life and possessed a scholarly knowledge of Persian and Urdu as well as English.

- Promoted : Sapru was appointed a member of the governor general's executive council and served on the Round Table Conferences in London and on the Joint Parliamentary Committee. As a liberal favoring moderate change within the constitutional and legal framework, Sapru worked untiringly in the role of mediator between the British authority and Indian nationalists and between Hindu and Muslim leaders. He sought, for example, to mediate between the Congress and the British in the Round Table Conferences but was unable to exact concessions from either side. In other instances he was successful, as with the Gandhi-Irwin Pact in 1931. He objected equally to Congress tactics of civil disobedience as prejudicial to compromise and to government imprisonment of Congress leaders.

- Sapru Committee : Most notably he was chairman of the Sapru Committee, appointed in November 1944 by the Standing Committee of the Non-party Conference. The committee was charged with examining the whole communal question in a judicial framework following the breakdown of the Gandhi-Jinnah talks on communal problems. Sir Tej selected 29 committee members representative of all communal groups. The committee submitted proposals to the viceroy, Lord Wavell, in an attempt to break the political deadlock.

- Report : The committee's report contained a detailed historical analysis of proposals and claims of each community and a rationale for its constitutional recommendations. On the critical question of partition, the Sapru Committee made a final but fruitless plea to avert the creation of Pakistan. Sapru was also a member of the defense committee in the 1945 trials of Indian National Army officers for treason. The defenses argued that as the INA was an independent army representing an independent government-in-exile, its officers could not be prosecuted for treason.

- Constituent Assembly : Throughout the constitutional debates Sapru played a key moderating role, appealing at each stage to Hindu and Moslem and to Englishman and Hindu to conciliate their differences. He sought in the process to safeguard the rights of each communal group. He died on Jan. 20, 1949.