Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - being learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

Pro-changers, No-changers and the Revolutionaries

1.0 INTRODUCTION

The withdrawal of the Non-Cooperation Movement after the Chauri Chaura violence led to serious demoralisation in the nationalist ranks. Gandhiji was insistent on the path of truth and non-violence alone to guide the movement. Others were not so sure. After Gandhiji’s arrest, there was the danger of the movement lapsing into passivity. Serious differences arose among the leaders who had to decide how to prevent this.

2.0 Pro-changers and No-changers

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Dr. Ansari, Babu Rajendra Prasad, and others continued to emphasise the constructive programme of spinning, temperance, Hindu-Muslim unity, removal of untouchability, and grass roots work in the villages and among the poor. This would, they said, gradually prepare the country for the new round of mass struggle. This group was called the No changers.

However, another school of thought headed by Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das and Motilal Nehru advocated a new line of political activity under the changed conditions. The Government of India Act of 1919 had introduced a new system of administration in the country. One of the main changes was that the legislature had become more representative. This group called the Pro-changers held the view that nationalists should end the boycott of the Legislative Councils, enter them, obstruct their working according to official plans, expose their weaknesses, transform them into arenas of political struggle, and thus use them to arouse public enthusiasm. The ‘no-changers’, opposed Council entry. They warned that legislative politics would lead to neglect of work among the masses, weaken nationalist fervour and create rivalries among the leaders.

2.1 The Swaraj Party

In December 1922, Das and Motilal Nehru formed the Congress-Khilafat Swarajya Party with Das as president and Motilal Nehru as one of the secretaries. The new party was to function as a group within the Congress. It accepted the Congress programme except in one respect - it would take part in Council elections.

The Swarajists and the ‘no-changers’ now engaged in fierce political controversy. Even Gandhiji, who had been released on 5 February 1924 on grounds of health, failed in his efforts to unite them. But both were determined to avoid the disastrous experience of the 1907 split at Surat. On the advice of Gandhiji, the two groups agreed to remain in the Congress though they would work in their separate ways. Finally an agreement was reached according to which, the Pro-changers were allowed Council entry on the condition that they would work in the Council on behalf of the Congress.

2.2 The elections in 1923

In spite of the very little time they got for preparations, the Swarajists did very well in the election of November 1923. They won 42 seats out of the 101 elected seats in the Central Legislative Assembly. With the cooperation of the Independents led by M.A. Jinnah and individuals such as Madan Mohan Malviya and co-ordinated floor management, they repeatedly out-voted the government in the Central Assembly and in several of the provincial councils. They agitated through powerful speeches on questions of self-government, Civil liberties and industrial development. In March 1925, they succeeded in electing Vithalbhai J. Patel, a leading nationalist leader, as the president (Speaker) of the Central Legislative Assembly.

The three major sets of issues the Swarajists took up were:

- constitutional advance leading to self-government,

- civil liberties, release of political prisoners and repeal of successive laws, and

- the development of indigenous industries.

The Swarajists filled the political void at a time when the national movement was recouping its strength. They also exposed the hollowness of the Reform Act of 1919. But they failed to change the policies of the authoritarian Government of India and found it necessary to walk out of the Central Assembly first in March 1926 and January 1930.

In the meanwhile, the ‘no-changers’ carried on quiet, constructive work. Symbolic of this work were hundreds of ashrams that came up all over the country where young men and women promoted charkha and khadi, and worked among the lower castes and tribal people. Hundreds of National Schools and Colleges came up where young persons were trained in a non-colonial ideological framework. These workers were to serve as the backbone of the civil disobedience movements later.

Though the Swarajists and the ‘no changers’ worked in their own separate ways, there was no basic difference between the two. They were on the best of terms and recognised each other’s anti-imperialist character. They could readily unite later when the time was ripe for a new national struggle. Meanwhile the nationalist movement and the Swarajists suffered another grievous blow in the death of Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das in June 1925.

3.0 Rise of communalism

As the Non-Cooperation Movement petered out and the people felt frustrated, communalism reared its ugly head. The communal elements took advantage of the situation to propagate their views and after 1923 the country was repeatedly plunged into communal riots. The Muslim League and the Hindu Mahasabha, which was founded in December 1917, once again became active. The result was that the growing national consciousness received a setback. Even the Swarajist Party, whose main leaders, Motilal Nehru and Das, were staunch nationalists, was split by communalism. A group known as ‘responsivists’, including Madan Mohan Malaviya, Lala Lajpat Rai and N.C. Kelkar, offered cooperation to the government so that the so-called Hindu interests might be safeguarded.

Motilal Nehru was accused of letting down Hindus, of being anti-Hindu, of favouring cow-slaughter, and of eating beef. The Muslim communalists were no less active in fighting for the loaves and fishes of office. Gandhiji, who had repeatedly asserted that “Hindu-Muslim unity must be our creed for all time and under all circumstances”, tried to intervene and improve the situation. In September 1924, he went on a 21 days fast at Delhi in Maulana Mohamed Ali’s house to do penance for the inhumanity revealed in the communal riots. But his efforts were of little avail.

4.0 Weaknesses of the Swaraj Party

The preoccupation with parliamentary politics started taking a toll on the internal cohesion of the Swaraj party. Having reached the limits of the politics of obstruction, further progress could be made only by a mass movement outside. The Government’s policy of trying to create dissension in the Swarajists’ ranks by pitting one group against the other began to bear fruit. In Bengal, the Swarajists failed to support the tenant’s cause against the zamindars and thereby lost the support of its pro-tenant members. Some of the Swarajist legislators also could not resist the pulls of parliamentary perquisites and positions of status and patronage. To prevent further dissolution and disintegration of the party, the spread of parliamentary corruption and and further weakening of the moral fibre of its members, the main leadership reiterated its faith in mass civil disobedience and withdrew from the legislature in 1926.

Though the Swarajists did contest elections one more time in November, 1926, they failed to make much headway.

The situation in the country appeared to be dark indeed. There was general political apathy; Gandhi was living in retirement, the Swarajists were split, communalism was flourishing. Gandhiji wrote in May 1927: “My only hope lies in prayer and answer to prayer”. But, behind the scenes, forces of national upsurge had been growing. When in November 1927 the announcement of the formation of the Simon Commission came, India again emerged from darkness and entered a new era of political struggle.

5.0 Emergence of new forces

1927 witnessed many portents of national recovery and the emergence of the new trend of socialism. Marxism and other socialist ideas spread rapidly. Politically this force and energy found reflection in the rise of a new left wing in the Congress under the leadership of Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose. The left wing did not confine its attention to the struggle against imperialism. It simultaneously raised the question of internal class oppression by the capitalists and landlords.

5.1 Indian youth

Indian youth were becoming active. All over the country youth leagues were being formed and student conferences held. The first All-Bengal Conference of Students was held in August 1928 and was presided over by Jawaharlal Nehru. After this, many other student associations were started in the country and hundreds of student and youth conferences held. Moreover, the young Indian nationalists began gradually to turn to socialism and to advocate radical solutions for the political, economic and social ills from which the country was suffering. They also put forward and popularised the programme of complete independence.

5.2 Socialist and communist ideologies

Socialist and Communist groups came into existence in the 1920s. The example of the Russian Revolution had aroused interest among many young nationalists. Many of them were dissatisfied with Gandhian political ideas and programmes and turned to socialist ideology for guidance. M.N. Roy became the first Indian to be elected to the leadership of the Communist International. In 1924, the government arrested Muzaffar Ahmed and B.A Dange, accused them of spreading Communist ideas, and tried them along with others in the Kanpur Conspiracy case. In 1925, the Communist Party came into existence. Moreover, many worker and peasant parties were founded in different parts of the country. These parties and groups propagated Marxist and communist ideas. At the same time they remained integral parts of the national movement and the National Congress.

5.3 Tenancy law protests, and industrial strikes

The peasants and workers were also once again stirring. In Uttar Pradesh, there was large-scale agitation among tenants for the revision of tenancy laws. The tenants wanted lower rents, protection from eviction and relief from indebtedness. In Gujarat, the peasants protested against official efforts to increase land revenue. The famous Bardoli Satyagraha occurred at this time. In 1928, under the leadership of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel the peasants organised a No Tax Campaign, and in the end won their demand. There was a rapid growth of trade unionism under the leadership of the All-India Trade Union Congress. Many strikes occurred during 1928. There was a long strike lasting for two months in the railway workshop at Kharagpur. The South Indian Railway workers went on strike. Another strike was organised in the Tata Iron and Steel Works at Jamshedpur. Subhash Chandra Bose played an important role in the settlement of this strike. The most important strike of the period was in Bombay textile mills. Nearly 150,000 workers went on strike for over five months. This strike was led by the Communists. Over five lakh workers took part in strikes during 1928.

6.0 The Revolutionaries

Another reflection of the new mood was the growing activity, of the revolutionary terrorist movement which too was beginning to take a socialist turn. The failure of the First Non-Cooperation Movement had led to the revival of the revolutionary movement. After an all India Conference, the Hindustan Republican Association was formed in October 1924 to organise an armed revolution. The Government struck at it by arresting a large number of terrorist youth and trying them in the Kakori Conspiracy Case (1925). Seventeen were sentenced to long terms of imprisonment, four were transported for life, and four, including Ram Prasad Bismil and Ashfaqulla, were hanged. The revolutionaries soon came under the influence of socialist ideas, and in 1928, under the leadership of Chandra Shekhar Azad changed the name of their organisation to the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA). They also gradually began to move away from individual heroic action and terrorism.

6.1 Assassination of Col. Saunders

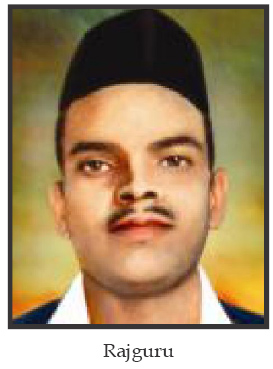

The brutal lathi-charge on an anti-Simon Commission demonstration on 30 October 1928 led to a sudden change. The great Punjabi leader Lala Lajpat Rai died as a result of the lathi blows. This enraged the youth and, on 17 December 1928, Bhagat Singh, Azad and Rajguru assassinated Saunders, the British police officer who had led the lathi charge.

The HSRA leadership also decided to let the people know about their changed political objectives and the need for a revolution by the masses. Consequently, Bhagat Singh and B.K. Dutt threw a bomb in the Central Legislative Assembly on 8 April 1929. The bomb did not harm anyone, for it had been deliberately made harmless. The aim was not to kill but; as their leaflet put it, “to make the deaf hear”. Bhagat Singh and B.K. Dutt could have easily escaped after throwing the bomb but they deliberately chose to be arrested for they wanted to make use of the court as a forum for revolutionary propaganda.

6.2 The Bengal armoury raid

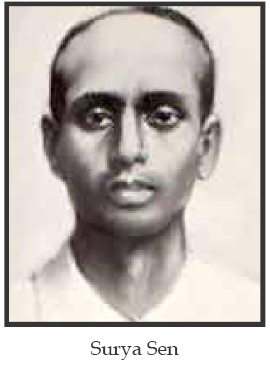

In Bengal too revolutionary terrorist activities were revived. In April 1930, a well-planned and large-scale armed raid was organised on the government armoury at Chittagong under the leadership of Surya Sen. This was the first of many attacks on unpopular government officials. A remarkable aspect of the revolutionary movement in Bengal was the participation of young women. The Chittagong revolutionaries marked a major advance. Theirs was not an individual action but a group action aimed at the organs of the colonial state.

The government struck hard at the revolutionary ‘terrorists’. Many of them were arrested and tried in a series of famous cases. Bhagat Singh and a few others were also tried for the assassination of Saunders. The statements of the young revolutionaries in the courts and their fearless and defiant attitude won the sympathy of the people. Their defence was organised by Congress leaders who were otherwise votaries of non-violence.

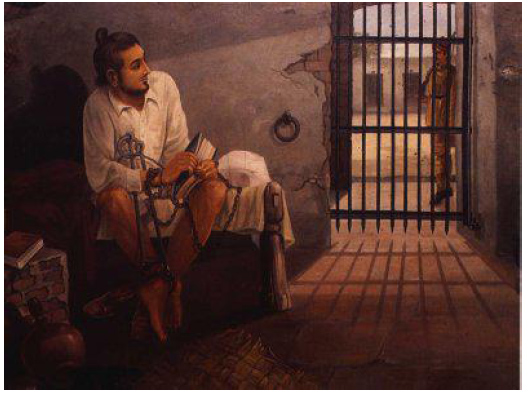

6.3 Bhagat Singh

Particularly inspiring was the hunger strike they undertook as a protest against the horrible conditions in the prisons. As political prisoners they demanded an honourable and decent treatment in jail. During the course of this hunger strike, Jatin Das, a frail young man, achieved martyrdom after a 63-day long epic fast. Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru were executed on 23 March 1931, despite popular protest. In a letter to the Jail Superintendent written a few days before their execution, the three affirmed: “Very soon, the final battle win begin. Its outcome will be decisive. We took part in the struggle and we are proud of having done so”.

In two of his last letters, the 23-year old Bhagat Singh also affirmed his faith in socialism. He wrote: “The peasants have to liberate themselves not only from foreign yoke but also from the yoke of landlords and capitalists”. In his last message of 3 March 1931 he declared that the struggle in India would continue so long as “a handful of exploiters go on exploiting the labour of the common people for their own ends. It matters little whether these exploiters are purely British capitalists, or British and Indians in alliance, or even purely Indian”. Bhagat Singh defined socialism in a scientific manner - it meant the abolition of capitalism and class domination. He also made it clear that much before 1930 he and his comrades had abandoned terrorism. In his last political testament, written on 2 February 1931, he declared:

“Apparently, I have acted like a terrorist. But I am not a terrorist. ... Let me announce with all the strength at my command that I am not a terrorist and I never was, except perhaps in the beginning of my revolutionary career. And I am convinced that we cannot gain anything through those methods”.

Bhagat Singh was also fully and consciously secular. He often told his comrades that communalism was as big an enemy as colonialism and was to be as firmly opposed. In 1926, he had helped establish the Punjab Naujawan Bharat Sabha and had become its first secretary. Two of the rules of the Sabha, drafted by Bhagat Singh, were: “To have nothing to do with communal bodies or other parties which disseminate communal ideas” and “to create the spirit of general toleration among the people considering religion as a matter of personal belief of man and to act upon the same fully”.

6.4 A new political reality

The revolutionary terrorist movement soon abated though stray activities were carried on for several years more. Chandra Shekhar Azad was killed in a shooting encounter with the police in a public park, later renamed Azad Park, at Allahabad in February 1931. Surya Sen was arrested in February 1933 and hanged soon after. Hundreds of other revolutionaries were arrested and sentenced to varying terms of imprisonment, some being sent to the Cellular Jail in the Andamans.

Thus a new political situation was beginning to arise by the end of the twenties. Writing of these years, Lord Irwin, the Viceroy, recalled later that “some new force was working of which even those, whose knowledge of India went back for 20 or 30 years, had not yet learnt the full significance”. The Government was determined to suppress this new trend. As we have seen, the terrorists were suppressed with ferocity. The growing trade union movement and Communist movement were dealt with in the same manner. In March 1929, thirty-one prominent trade union and Communist leaders (including three Englishmen) were arrested and, after a trial (Meerut Conspiracy Case) lasting four years, sentenced to long periods of imprisonment.