Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - being learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

Landmark cases and important articles of the

Indian Constitution - Part 1

1.0 INTRODUCTION

In the parliamentary history of India, often it has happened that when the legislature or the executive has failed in discharging its constitutional duties or has acted ultra vires the constitution, the judiciary has stepped in (interfered, for some) to safeguard the provisions of our Constitution.

The British parliamentary system has left a lasting impression on the Indian constitution due to the colonial legacy. The concept of freedom of the judiciary was taken from the USA. The USA did impart considerable power to the judiciary and made the judiciary free of the biased influence of the executive and the legislature.The USA set an example of freedom of judiciary for the whole world.

It is pertinent to point out that the Supreme Court of the USA is the earliest in the modern democratic world. The USA is one of the countries to have adopted the 'principle of separation of powers'. There is a clear and distinct line that separates the three major organs - the executive, the legislature and the judiciary. As a result the USA had had a glorious past of 200 years of peace, progress and harmony. The main reason is that the powers of the three organs of the government are obviously written in the Constitution.

Since the legislature represents the people, controls the government and makes laws, no one can interfere with its freedom and authority to do so. However the judiciary has to adjudicate disputes, interpret the Constitution, "declare the law" and pass the necessary order "for doing complete justice". The Supreme Court is the final authority for interpreting and pronouncing on the provisions of a law. Any law which violates the constitutional provisions is invalidated. The power of judicial review has always been there with the Supreme Court and cannot be taken away. The executive operates and enforces the law made by the legislature. However, a number of occasions have come in the parliamentary history of our country when there is a tug of war between the legislature and the judiciary. In fact the tug of war between the executive government and courts has occurred ever since the courts have been established.

In the parliamentary history of India it has happened several times that when the legislature or the executive failed in its constitutional duties, then the judiciary had to interfere to safeguard the provisions of our Constitution and to protect larger public interest. As corruption is understood to be rampant among top bureaucrats and political leaders, the increased expectation of common man from the judiciary can easily be understood.

Lack of transparent governance and economic growth has resulted in the frustrated public turning to the courts for giving mandatory orders to the governments to sort out the mess. This aweful decline in the efficiency of the legislators has put them under the scrutiny of the judiciary and challenged their supremacy that had stayed uncontested since the times of Nehru. Experts say that several cliques of functionaries, dependants and parasites under the socialist raj bolstered the primacy of the legislators, which is now in question. It is also clear that the political elite have under their patronage many mediocres who secure positions and favours which they cannot secure through fair means of promotion, and who continue to support the myth of the supremacy of the parliamentarians. The past few years - especially after the advent of mass media and social media - have brought the incongruencies in sharp relief.

2.0 THE CONCEPT OF JUDICIAL REVIEW

The Supreme Court has been vested with the power of judicial review. It means that the Supreme Court may review its own Judgements. Judicial review can be defined as the competence of a court of law to declare the constitutionality or otherwise of a legislative enactment.

Being the guardian of the fundamental rights and arbiter of the constitutional conflicts between the Union and the States with respect to the division of powers between them, the Supreme Court enjoys the competence to exercise the power of reviewing legislative enactments both of Parliament and the State's legislatures.

The power of the court to declare legislative enactments invalid is provided by the Constitution under Article 13, which declares that every law in force, or every future law inconsistent with or in derogation of the Fundamental Rights, shall be void. Other Articles of the Constitution (131-136) have also expressly vested in the Supreme Court the power of reviewing legislative enactments of the Union and the States.

The jurisdiction of the Supreme Court was curtailed by the 42nd Amendment of the Constitution (1976), in several ways. But some of these changes were repealed by the 43rd Amendment Act, 1977. But there are several other provisions which were introduced by the 42nd Amendment Act 1976 not repealed so far.

These are:

- Arts. 323 A-B - The intent of these two new Articles was to take away the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court under Art. 32 over orders and decisions of Administrative Tribunals. These Articles could, however, be implemented only by legislation. Art. 323A has been implemented by the Administrative Tribunals Act, 1985.

- Arts. 368 (4)-(5) - These two Clauses were inserted in Art. 368 with a view to preventing the Supreme Court to invalidate any Constitutional Amendment Act on the theory of 'basic features' of the Constitution.

These clauses have been emasculated by the Supreme Court itself, striking them down on the ground that they are violative in the two 'basic features' of the Constitution:

- the limited nature of the amending power under Art. 368 and

- judicial review, in the Minerva Mills case.

The court was very reluctant and cautious to exercise its power of Judicial Review, during the first decade of independence, when it declared invalid only one of total 694 Acts passed by the Parliament.

During the second decade of independence (1960), the court asserted its authority without any hesitation which is reflected in the famous Golak Nath case and Keshavananda Bharti case. In these cases the Supreme Court assumed the role of constitution making.

Indian Judiciary has been able to overcome the restriction that was put on it by the 42nd amendment, with the help of the 43rd and 44th amendments. Now the redeeming quality of Indian judiciary is that no future governments could clip its wings or dilute its right of Judicial Review. In fact, now 'Judicial Review' is considered to be the basic feature of our Constitution.

2.1 Constitutional Provisions for Judicial Review

The Indian Constitution adopted judicial review concept on lines of the U.S. constitution. Parliament is not supreme under the constitution of India. Its powers are limited in a manner that the power is divided between centre and states.

Moreover, the Supreme Court enjoys a position which entrusts it with the power of reviewing the legislative enactments both of the Parliament and the State Legislatures. This grants the court a powerful instrument of judicial review under the constitution.

Both the political theory and text of the Constitution has granted the judiciary the power of judicial review of legislation. The Constitutional Provisions which guarantee judicial review of legislation are Articles 13, 32, 131-136, 143, 145, 226, 246, 251, 254 and 372.

- Article 372 (1) establishes the judicial review of the pre-constitution legislation.

- Article 13 declares that any law which contravenes any of the provisions of the part of Fundamental Rights shall be void.

- Articles 32 and 226 entrust the roles of the protector and guarantor of fundamental rights to the Supreme and High Courts.

- Article 251 and 254 state that in case of inconsistency between union and state laws, the state law shall be void.

- Article 246 (3) ensures the state legislature's exclusive powers on matters pertaining to the State List.

- Article 245 states that the powers of both Parliament and State legislatures are subject to the provisions of the constitution.

The legitimacy of any legislation can be challenged in the court of law on the grounds that the legislature is not competent enough to pass a law on that particular subject matter; the law is repugnant to the provisions of the constitutions; or the law infringes one of the fundamental rights.

Articles 131-136 entrust the court with the power to adjudicate disputes between individuals, between individuals and the state, between the states and the union; but the court may be required to interpret the provisions of the constitution and the interpretation given by the Supreme Court becomes the law honoured by all courts of the land.

There is no express provision in our constitution empowering the courts to invalidate laws, but the constitution has imposed definite limitations upon each of the organs, the transgression of which would make the law void. The court is entrusted with the task of deciding whether any of the constitutional limitations has been transgressed or not.

3.0 THE BASIC STRUCTURE CONTROVERSY

The argument that the Parliament’s amending power is subject to substantive limitations was first raised in Sankari Prasad Deo v. Union of India, in 1951. The Constitutional challenge had arisen with respect to Part III of the Constitution, which contains fundamental rights such as the rights to life, equality, freedom of expression etc. The challenge in Sankari Prasad case was premised upon the wording of Article 13 of the Constitution, which prohibits the State from making any law in violation of any fundamental right enumerated in Part III. It was argued that a Constitutional amendment was “law”, properly called; and so, under Article 13, it was impermissible for the State to amend Part III of the Constitution. The argument was unanimously rejected by a constitution bench of the Supreme Court, which held that the Parliament had the power to amend any provision of the Constitution, without exception.

The question came up again fourteen years later in Sajjan Singh v. State of Rajasthan, (1964) also before a Constitution bench. Gajendragadkar C.J., speaking for himself and two others, upheld Sankari Prasad. However, Justices Hidayatullah and Mudholkar expressed doubts about the verdict. Hidayatullah J. opined that the many assurances given in Part III made it difficult to visualize fundamental rights as mere “playthings of a special majority.” Mudholkar J. observed that the framers may have intended to give permanency to certain “basic features” such as the three organs of the State, separation of powers etc. He also questioned whether a change in the basic features of the Constitution could be defined as an “amendment” within the meaning of Article 368, or whether it would amount to rewriting the Constitution itself.

The position of law was then reversed in Golak Nath v. State of Punjab, 1967. An eleven judge bench of the Supreme Court, by a slender margin of 6 to 5, and by divided majority opinions, held that the Parliament had no power. The next two decades saw the consolidation of the doctrine. In a series of judgments, which may collectively be called the Tribunals Cases, it was held that judicial review of the Supreme Court under Article 32, and of the High Courts under Article 226, was a basic feature. First enunciated in S.R. Bommai v. Union of India, and then crystallized in the decisions of Ismail Faruqui v. Union of India and Aruna Roy v. Union of India, the Court developed the concept of the basic feature of secularism as an attitude of even-handedness towards all religions. In I.R. Coelho v. State of Tamil Nadu, the Court added Articles 14 (right to equality), Article 19 (fundamental freedoms) and Article 21 (right to life) to the list of basic features.

It is also important to note certain other landmark judgments where basic structure challenges were rejected. In Kuldip Nayar v. Union of India, 2006, both secret ballots, and domicile requirements for election to State legislative Assemblies were held not to be basic features. In M. Nagaraj v. Union of India, 2002, the Constitutional amendment introducing Articles 16(4A) and 16(4B), was impugned. These articles dealt with certain specifics of affirmative action. Rejecting the contention that these provisions damaged equality, the Court observed that they only enunciated certain specific rules of “service jurisprudence”, not affecting the basic feature of equality under Articles 14, 15 and 16 of the Constitution.

This brief overview highlights the following salient points: first, basic structure review is a substantive limitation upon the power of the Parliament to amend the Constitution, i.e., Constitutional amendments must conform to certain standards or values, and must not be in violation of certain substantive content, in order to remain constitutionally true and valid; secondly, the task of judging content-based violations of the basic structure must be performed by the judiciary; and thirdly, the components of the basic structure doctrine, such as democracy, the rule of law, secularism etc., have been enunciated in a highly abstract manner, permitting varying and different interpretations. It is this framework that must be kept in mind while analyzing the legitimacy of the basic structure doctrine

4.0 The Shah Bano Case

A prominent case was the Muslim Women (Right to Protection on Divorce) Act, 1986, popularly known as the Shah Bano case, exempting Muslims from obligations to financially support ex-wives. It was enacted by the Congress government of Rajiv Gandhi who untiringly claimed to take India to the 21st century but in actuality, succumbed to the pressure of the ultra-conservative Muslim clergy that always insisted on a certain version of Shariyat laws that severely curtail the freedom of Muslim women in joining the modern mainstream life. The ruling given by the Supreme Court of India that paved a well-lit path for Muslim divorcee women by awarding the same benefits that were available to the majority Hindu women. Begum Shah Bano, a middle-aged Muslim woman from Indore, Madhya Pradesh, was divorced/given triple talaq by her husband, MA Khan after 43 years of marriage. She filed a petition in the state High Court that as an Indian citizen she was entitled to financial support from her former husband. This penurious Muslim woman claimed for maintenance from her husband under Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. The Supreme Court judges in 1985 held that the Muslim woman have a right to get maintenance from her husband under Section 125.

They observed: "This appeal, arising out of an application filed by a divorced Muslim woman for maintenance under section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, raises a straightforward issue which is of common interest not only to Muslim women, not only to women generally, but to all those who, aspiring to create an equal society of men and women, lure themselves into the belief that mankind has achieved a remarkable degree of progress in that direction. Under section 125 (1) (a), a person, who, having sufficient means, neglects or refuses to maintain his wife who is unable to maintain herself, can be asked by the Court to pay a monthly maintenance to her at a rate not exceeding five hundred rupees …'wife' includes a divorced woman who has not remarried."

They pointed out whether the spouses are Hindus or Muslims, Christians or Parsis matter little, as section 125 is a part of the Code of Criminal Procedure, not of the civil laws, which define and govern the rights and obligations of the parties belonging to particular religions. This section was enacted to provide a quick relief to those who are unable to maintain themselves. It goes across the barriers of religion even though it does not supplant the personal law of the parties.

The Supreme Court also tried to interpret the holy Quran liberally by pointing out that the verse 241 for divorced women says that "Maintenance (should be provided) on a reasonable (scale). This is a duty on the righteous." They also rejected the hard-hearted plea of the All India Muslim Personal Law Board that in verse 241, the exhortation is to the more pious and not to all Muslims. Angry voices were raised against the verdict, leading to demonstrations all over India. The orthodox stand was that Section 125 CrPC couldn't apply to Muslims. Accepting maintenance beyond the iddat period was haraam (illegitimate) under the Shariat as all relationship between a man and his wife would have ceased. Iddat is a three months period to ascertain whether the woman is pregnant or not and if with the child, only the child is entitled to support from the father. After the triple utterance the woman could be supported either by her relatives or the Wakf Board. Islam does not allow alimony beyond the period of iddat, said the clergy.

To appease the orthodox, the Rajiv Gandhi's government skirted the issue that a secular relief in addition to the personal law can be given to Muslim women even though divorce may be decided according to Muslim personal law.

The Congress party succumbed to the clergy and brought in the Muslim Women's Act, 1986. Apart from performing a ritual lip service of opposition, the well-sung progressives of the Anglophonic class also submerged into silence and some of them even sang odes in praise of the Congress for upholding the sanctity of the Shariyat. This, to many, was a classic case of hypocrisy of the 'progressives', who routinely hold that a 21st century outlook favoring departure from older laws permitting of polygamy or primogeniture, is mandatory for the Hindu majority of India, while a perpetuation of Islamic and Christian orthodoxy for the sake of bishops and imams (who are often willing agents in the vote hunting of political parties) is in the interest of Muslims and Christians as it 'protects' their minority rights. 'Progress' thus seemed to prescribe one direction for Hindus and another for minorities. Not only does it make a mockery of the very idea of progress, it also ghettoizes the minorities leading to their alienation and profiling in Indian society. The Shah Bano Act helped to perpetuate the social isolation of Muslim women and their utter submission to the unbudging and ever fossilizing clerics who now frequently issue fatwas regarding women over and above the law of land. This outcome of the Shah Bano amendment has not been adequately scrutinized in the intellectual circles or universities dissertations on minorities.

Shah Bano Case and Triple Talaq law

- In 2016, the Supreme Court sought assistance from the Attorney General on pleas challenging the constitutional validity of “triple talaq”, “nikah halala” and “polygamy”, to assess whether Muslim women face gender discrimination in cases of divorce.

- Opposing the practice of triple talaq, the Centre said that there is a need to re-look at these practices on grounds of gender equality and secularism. The Supreme Court set up a five-judge constitutional bench to hear the challenges against the practice of ‘triple talaq, nikah halala’ and polygamy.

- In March 2017, the All India Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB) told the SC that the issue fell outside the judiciary’s realm. But on August 22 2018, the Supreme Court set aside the decades-old practice of instant triple talaq saying it was violative of Article 14 and 21 of the Indian Constitution.

- The bench comprising five judges was headed by Chief Justice J. S. Khehar. The court’s ruling was restricted to the constitutional validity of triple talaq and did not include issues like polygamy and nikah halala under the Muslim personal law. Despite the SC ruling Triple Talaq as unconstitutional, the Union Government pushed through a Bill on the matter, later.

- The Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Bill, 2018 was introduced in Lok Sabha on December 17, 2018. It replaced an Ordinance promulgated on September 19, 2018. The LS passed it.

- The Bill made all declaration of triple talaq, including in written or electronic form, to be void (i.e. not enforceable in law) and illegal. It defines talaq as talaq-e-biddat or any other similar form of talaq pronounced by a Muslim man resulting in instant and irrevocable divorce. Talaq-e-biddat is the practice of pronouncement of ‘talaq’ thrice in one sitting by a Muslim man.

- Offence and penalty: The Bill makes declaration of talaq a cognizable offence, attracting up to three years’ imprisonment with a fine.

- Criticism : Since the SC verdict outlawed the practice, there was no need to bring a separate law, criminalising the Act. It is for the first time that an action in a civil matter (marriage) was criminalised.

5.0 Section 498 A OF THE INDIAN PENAL CODE

A typical example of attempting to remove a social evil (in this case of dowry and cruelty to married women) by making an over-harsh law is the case of a special provision called Section 498A, which defines the offence of matrimonial cruelty. This was inserted into the Indian Penal Code by an amendment in 1983. Offenders can be imprisoned as well as fined under the section. The offence is non-bailable, non-compoundable and cognizable on a complaint made to the police by the victim or her relatives.

The section defines the meaning of cruelty as follows:

- any willful conduct which is of a nature as is likely to drive the woman to commit suicide or to cause grave injury or danger to her life, limb, or health (whether physical or mental of the woman; or

- harassment of the woman where such harassment is with a view to coercing her or any person related to her to meet any unlawful demand for any property or valuable security or is on account of failure by her or any person related to her to meet such demand.

Made with the best intentions the law has met with a strange fate. It has not been able to provide the sought relief to the real victims specially those who come from poor or rural sections but it has been brazenly abused in urban areas by unscrupulous women and their families with the help of lawyers. Even in divorce cases matters filed on grounds of incompatibility, lawyers frequently, rather as a rule, suggest to their woman client to take recourse to this section to pressurize the husband to meet her demands sheepishly.

The report of the Malimath Committee, submitted in April 2003, while ostensibly discussing the reform of the Criminal Justice System, discusses the "heartless provisions" of section 498A. The Committee (16.4.4) depicts the situation where:

"a less tolerant and impulsive woman may lodge an FIR even on a trivial act. The result is that the husband and his family may be immediately arrested and there may be a suspension or loss of job. The offence alleged being non-bailable, innocent persons languish in custody. There may be a claim for maintenance adding fuel to fire, especially if the husband cannot pay. Now the woman may change her mind and get into the mood to forget and forgive. The husband may also realize the mistakes committed and come forward to turn over a new leaf for a loving and cordial relationship. The woman may like to seek reconciliation. But this may not be possible due to the legal obstacles. Even if she wishes to make amends by withdrawing the complaint, she cannot do so as the offence is non-compoundable. The doors for returning to family life stand closed. She is thus left at the mercy of her natal family."

The Committee recommends that the section be made bailable and compoundable to provide space and time for reconciliation. The Committee rightly suggests that the amendment shall be good for women as they would be able to get better maintenance which is denied now as the husband often loses his job in the pendency of the cases.

After report of the Malimath Committee, the judgment of the Delhi High Court on 19 May 2003 in the case of Savitri Devi v. Ramesh Chand and others took up the issue of "misuse." The Hon'ble Justice J.D. Kapoor, who has also taken up the matter in his book, Laws and Flaws in Marriage: How to Remain Happily Married, in his judgment discusses section 498A. He "feel(s) constrained to comment" upon it as it "hit[s] at the foundation of marriage itself and has not proved to be so good for the health of the society at large." For him, section 498A results in the social catastrophe of thousands of divorce cases, primarily due to arrest of members of the family and the consequent reduction attrition that closes the chances of salvaging the marriage.

He notes that in the Indian system of remarriage is not so easy and women lacking in economic independence become a burden over their parents and brothers. He also notes the misuse of the provisions of section 498A by women complainants and the police. He acutely observes that the police are "bad and unskilled masters" in whose "iron and heavy hands" the "ticklish and complex" issue of domestic disputes should not be left. Further, the "misuse" by women complainants is explained only as the "growing tendency" among women to rope in each and every relative in the complaint. He ends up concluding that these "provisions were though made with good intentions but the implementation has left a very bad taste and the move has been counterproductive." He suggests that the Section 498A/ 406 IPC be made bailable, and necessarily compoundable.

A special leave petition (SLP) was filed in the Supreme Court of India, Sushil Kumar Sharma Vs. Union of India (UOI) and Ors - Jul 19 2005, Citation: JT 2005 (6) SC 266, Case No: Writ Petition (C) No. 141 of 2005, Judgment: Jul 19 2005 - in which the prayer was to declare Section 498A to be unconstitutional and ultra vires and in the alternative to formulate guidelines so that innocent persons are not victimized by unscrupulous persons making false accusations. Further prayer was made that whenever, any court comes to the conclusion that the allegations made regarding commission of offence under Section 498A IPC are unfounded, stringent action should be taken against person making the allegations.

6.0 Conflicts over the Reservation issue

Regarding the legality and constitutionality of reservation laws, the Indian Supreme Court has indeed come a long way from the approach in M.R. Balaji v. State of Mysore, 1963, where it struck down a law mandating 68% reservation, questioning the findings of the Nagan Gowda Committee Report. Subsequently, in the cases of Indira Sawhney v. Union of India, Ashok Kumar Thakur v. Union of India, M. Nagaraj v. Union of India and most recently in Indian Medical Association v. Union of India, the Court has been far more liberal with reservation legislation/constitutional amendment, much to the joy of social activists/legal reformists.

In the new set of case law, the Courts have given the executive a near-free reign, saying that as long as the reservation is not founded on a palpably erroneous/biased policy, is based on certain relevant fact-finding reports of Commissions/Committees and seeks to serve the larger ideal of social justice, the Court would be reluctant to interfere with the policy of the Executive.

A similar jurisprudence of 'trusting the executive' to carry out its mandate in a bonafide manner and not abuse a power granted to it, even if unfettered, can be seen in C.J.Sastri's dissent in Anwar Ali Sarkar (AIR 1952 SC 75), the majority decisions in Maganlal Chhaganlal vs. Greater Bombay Municipal Corporation (AIR 1974 SC 2009) and the much-chastised majority view in the Habeas Corpus case (AIR 1976 SC 1207). This approach, in the context of reservation legislation, has been lauded by activists and civil society, as the Supreme Court coming of age and finally understanding the true import of its constitutional mandate of social justice.

However, a similar approach of the Court in cases like BALCO Employees Association v. Union of India (2002 (2) SCC 333), where it has taken a similarly lenient and trusting view of Executive policy, these same activists have severely criticised the Court's approach of judicial restraint. True, these cases involved policies representative of a marked departure from India'spolicy of preambulatory socialism and social justice in many ways, but it must be borne in mind that the essence of challenge in both cases was to a policy choice of the Executive. In the first set of cases, activists celebrated the Courts refusal, in Ashok Kumar Thakur, to apply the doctrine of strict scrutiny to reservation laws in India, but it is almost these same activists who prescribe an almost similarly strict test for economic reform legislation/executive action in the country.

In a recent verdict the apex court of India while considering the plea of Faculty Association of AIIMS opined that reservation need not be implemented in medical institutions' super specialty divisions like AIIMS, referring to the famous Indira Sawhney's case which dealt with the Mandal commission recommendation for backward caste reservation in public institutions, quoting it as binding.

It toed the guideline propounded by same case wherein it was held that "it may not be advisable to provide for reservations. For example, technical posts in research and development organizations/ departments/ institutions, in specialties and super specialties in medicine, engineering and other such courses in physical sciences and mathematics, in defense services and in the establishments connected therewith." This clearly is indicative of the perceptual perversions that certain communities do not hold ability to produce certain acumen or intellectual faculties, as referred in Indira Sawhney's case. It was in this very case of "Indira Sawhney vs. Union of India", that the Apex Court formulated concept of ‘creamy layer differentiating among people from same communities on the basis of their economic deprivation and empowerment’. Further, Loksabha took it as an assault on its supremacy and a decision against the 80% of the country's population.

The Supreme Court while deciding to examine the constitutional validity of the Tamil Nadu law providing for 69 per cent quota in employment and educational institutions, directed the State government to create additional seats in the first year MBBS for meritorious students affected by the quota law. A bench of justices comprising K. S. Radhakrishnan and A. K. Sikri gave this direction on a petition filed by R. Harshini, who could not secure admission in MBBS despite securing 911th rank.

RESERVATIONS FOR THE “POOR” - 2019

- The government moved quickly in the month of January 2019 to amend the constitution, and bring in, for the first time, a provision to reserve seats in educational institutions and government jobs for economically weaker sections of society, who did not have any reservations till date (so, no SCs, STs, OBCs)

- Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha hurriedly passed the Bill for providing 10 per cent reservation in government jobs and non-minority educational institutions, to the "poor sections of society".

- The Bill was titled - "The Constitution (One Hundred and Twenty Fourth Amendment) Bill". It was the 103rd amendment, passed on 12-01-2019.

- The Bill amended Articles 15 and 16 of the Constitution, and the overall upper cap of 50% in reservations, set by the SC, too stands breached. The Act may not stand judicial scrutiny ultimately.

7.0 APPOINTMENT OF JUDGES AND THE COLLEGIUM CONTROVERSY

Under the collegium system, appointments and transfers of judges are decided by a forum of the Chief Justice of India and the four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court. It does not find mention in the Indian Constitution, though.

Article 124 deals with the appointment of Supreme Court judges. It says the appointment should be made by the President after consultation with such judges of the High Courts and the Supreme Court as the President may deem necessary. The CJI is to be consulted in all appointments, except his or her own.

Article 217 deals with the appointment of High Court judges. It says a judge should be appointed by the President after consultation with the CJI and the Governor of the state. The Chief Justice of the High Court concerned too should be consulted.

The collegium system has its genesis in a series of three judgments that is now clubbed together as the "Three Judges Cases". The S P Gupta case (December 30, 1981) is called the "First Judges Case". It declared that the "primacy" of the CJI's recommendation to the President can be refused for "cogent reasons". This brought a paradigm shift in favour of the executive having primacy over the judiciary in judicial appointments for the next 12 years.

On October 6, 1993, came a nine-judge bench decision in the Supreme Court Advocates-on Record Association vs Union of India case - the "Second Judges Case". This was what ushered in the collegium system. The majority verdict written by Justice J S Verma said "justiciability" and "primacy" required that the CJI be given the "primal" role in such appointments. It overturned the S P Gupta judgment, saying "the role of the CJI is primal in nature because this being a topic within the judicial family, the executive cannot have an equal say in the matter. Here the word 'consultation' would shrink in a mini form. Should the executive have an equal role and be in divergence of many a proposal, germs of indiscipline would grow in the judiciary."

Justice Verma's majority judgment saw dissent within the bench itself on the individual role of the CJI. In a total of five judgments delivered in the Second Judges case, Justice Verma spoke for only himself and four other judges. Justice Pandian and Justice Kuldip Singh went on to write individual judgments supporting the majority view. But Justice Ahmadi had dissented and Justice Punchhi took the view that the CJI need not restrict himself to just two judges (as mentioned in the ruling) and can consult any number of judges if he wants to, or none at all.

For the next five years, there was confusion on the roles of the CJI and the two judges in judicial appointments and transfers. In many cases, CJIs took unilateral decisions without consulting two colleagues. Besides, the President became only an approver.

In 1998, President K R Narayanan issued a presidential reference to the Supreme Court as to what the term "consultation" really means in Articles 124, 217 and 222 (transfer of HC judges) of the Constitution. The question was if the term "consultation" requires consultation with a number of judges in forming the CJI's opinion, or whether the sole opinion of the CJI constituted the meaning of the articles. In reply, the Supreme Court laid down nine guidelines for the functioning of the coram for appointments/transfers; this came to be the present form of the collegiums.

Besides, a judgment dated October 28, 1998, written by Justice S P Bharucha at the head of the nine-judge bench, used the opportunity to strongly reinforce the concept of "primacy" of the highest judiciary over the executive. This was the "Third Judges Case".

In July 2013, newly appointed Chief Justice P. Sathasivam spoke against any attempts to change the collegium system.

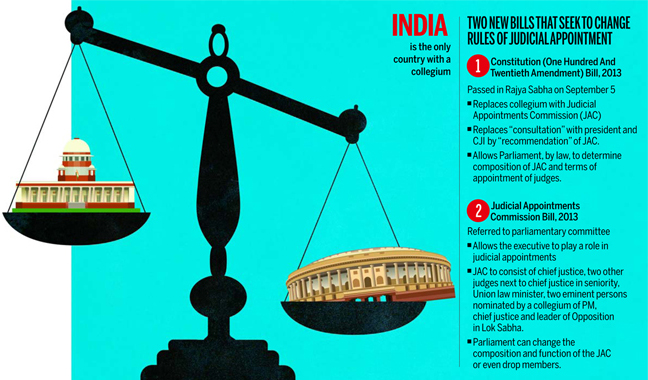

On the 5th of September, 2013, the Rajya Sabha passed The Constitution(120th Amendment) bill, 2013, that amends articles 124(2) and 217(1) of the Constitution of India, 1950 and establishes the Judicial Appointment Commission, on whose recommendation the President would appoint judges to the higher judiciary. The critical aspect about the new setup that the Government through the amendment seeks to achieve is the composition of the judicial appointment commission, the responsibility of which the amendment bill lays on the hands of the Parliament to regulate by way of Acts, rules, regulations etc. passed through the regular legislative process.

On December 31, 2014, the NJAC Act got Presidential assent. On April 13, 2015 the NJAC Act was notified. Soon, PILs were filled in the Supreme Court challenging it. On October 16, 2015, the Supreme Court scrapped the Act!

8.0 The debate about Article 8 (4)

The controversy over the Supreme Court decision declaring Section 8(4) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 ultra vires the Constitution seems to be turning into a legal debate. Legal experts are asking how come such an order was passed by a Division Bench when a Constitution Bench had already declared that the provision was "not unreasonable".

Section 8(4) allowed convicted MPs, MLAs and MLCs to continue in their posts, provided they appealed against their conviction/sentence within three months of the trial court judgment.

Senior lawyer and former Rajya Sabha member of the DMK R. Shanmugasundaram told The Hindu on Friday that he had doubts whether the latest verdict would stand the test of law. For, the Constitution Bench, in the K. Prabhakaran vs. P. Jayarajan case, said on January 11, 2005: "The persons falling in the two groups [those who are convicted before the poll and those convicted while being MPs/MLAs or MLCs] are well defined and determinable groups and, therefore, form two definite classes. Such classification cannot be said to be unreasonable as it is based on a well laid down differentia and has nexus with a public purpose sought to be achieved."

The Bench - headed by the then Chief Justice R. C. Lahoti and consisting of Justices Shivaraj V. Patil, K. G. Balakrishnan, B. N. Srikrishna and G. P. Mathur - even observed that Section 8 (4) was an "exception." Sub-section 4 "operates as an exception carved out from sub-sections (1), (2) and (3) of Section 8 of the RP Act."

Another lawyer and Tamil Nadu Congress Committee president B.S. Gnanadesikan said the legal issue involved now was whether the Division Bench could deviate from the verdict of the Constitution Bench. The exception from disqualification given to the elected representatives under Section 8 (4) (provided they appealed within three months) was a well thought-out provision in the interest of the country. Mr. Gnanadesikan suggested that a special law be enacted to ensure that such an appeal (against conviction) was disposed of within a month by the court concerned.

Legal experts pointed out that the Constitution Bench in 2005, while dealing with Section 8 (4), had observed:

"Once the elections have been held and a House has come into existence, it may be that a member is convicted and sentenced. Such a situation needs to be dealt with on a different footing. Here the stress is not merely on the right of an individual to contest an election or to continue as a member, but [on] the very existence and continuity of a House democratically constituted.

"If a member was debarred from sitting in the House and participating in the proceedings, no sooner [than] the conviction was pronounced followed by sentence of imprisonment, entailing forfeiture of his membership, then two consequences would follow. First, the strength of membership of the House shall stand reduced, so also the strength of the political party to which such convicted member may belong. The government in power may be surviving on a razor-thin majority where each member counts significantly and disqualification of even one member may have a deleterious effect on the functioning of the government.

"Secondly, a by-election shall have to be held which exercise may prove to be futile, also resulting in complications in the event of the convicted member being acquitted by a superior criminal court. Such reasons seem to have persuaded Parliament to classify the sitting members of a House in a separate category.

"..The disqualification provision must have a substantial and reasonable nexus with the object sought to be achieved and the provision should be interpreted with the flavour of reality bearing in mind the object for enactment."

"Sub-section (4) operates as an exception carved out from sub-sections (1), (2) and (3) of Section 8 of the RPA. Clearly the saving from the operation of sub-sections (1), (2) and (3) is founded on the factum of membership of a House. The purpose of carving out such an exception is not to confer an advantage on any person; the purpose is to protect the House."

The above is from the Hindu dated 13th July, 2013.

9.0 Economic Implications of the mining ban in India

Shipments of iron ore plunged to 18 million tonnes in 2012-13 from nearly 168 million tonnes in 2010-11. Ban on mining by the Supreme Court has hit the economy and exports besides increasing India's dependence on imported coal.

According to the Commerce and Industry Minister Anand Sharma the mining ban has hurt our economy. It has hurt exports, (particularly) iron ore exports. It has increased our dependence on coal imports. But for the ban on mining, he said, India could have earned by exporting around 100 million tonnes of iron ore.

"We have been deprived of the precious foreign exchange, and what we could have mined in India. When it comes to coal, $22 billion plus was the coal import bill," the Minister said adding: "these are the areas which need a serious look."

The Supreme Court had banned iron ore mining in Karnataka in July-August, 2011, and in Goa in October, 2012. Earlier, Mr. Sharma has raised concerns over judicial activism, and said, "India badly needs judicial reforms.'' Following the ban, shipments of iron ore plunged to 18 million tonnes in 2012-13 from nearly 168 million tonnes in 2010-11. Before the ban, India was exporting iron ore worth over $7 billion.

As regards coal, the environmental restrictions have significantly hampered coal production in the country, leading to increase in dependence on coal imports. Slowdown in exports has increased the trade deficit as well as the current account deficit.

While the trade deficit soared to a record high of $191 billion in 2012-13, CAD jumped to $88.2 billion, or 4.8 per cent of the GDP during the period. The mining sector, with a weight of about 14 per cent in Index of Industrial Production (IIP), saw a contraction of 3.5 per cent in October as against a dip of 0.2 per cent in the same month last fiscal. During April-October, the output shrank by 2.7 per cent as against a contraction of one per cent. Coal production, with a weight of about 4.5 per cent in the IIP, declined by 3.9 per cent in October.

mining ban

- Traditionally, only public sector companies in India were given mining licences. But then private players were allowed to mine as demand grew. A mining licence is granted for a minimum period of 20 years and a maximum period of 30 years and for a maximum area of 10 sq. km.

- Some private firms ‘stretched’ operations beyond the leased areas. They did not even pay due royalty and taxes, and flouted environmental norms on dumping the waste. ‘Illegal mining’ was born. Locals near the mines suffered from pollution.

- Goa's mining industry had faced a ban in 2012 after an SC directive which had taken cognisance of the M B Shah panel's report that claimed there was illegal mining worth Rs 35,000 crore in the state between 2005 and 2012.

- The industry remained banned for nearly 19 months from October 2012 to April 2014, when the SC finally allowed the industry to operate imposing several riders.

- But due to non-compliance of conditions of resuming of mining by the State government, the Supreme Court in February 2018 put a complete ban on iron-ore mining in the State of Goa.

10.0 Section 377 and the supreme court judgement

Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 makes certain acts illegal. It is an archaic colonial law that was brought in by the British. The section seems neutral in that it criminalizes certain sexual acts and not people and their identities. However, it has never been used against consenting heterosexual persons and has been misused against homosexual persons. The primary problem with the provision of law is that it does not take into consideration age or consent. Therefore, it criminalizes adult consensual same sex acts.

The fight against section 377 has been going on since 2001 before the courts. It started with the petition by Naz Foundation before the High Court of Delhi. Subsequently Naz Foundation was joined by other petitioners. The Delhi High court gave its judgment in Naz Foundation v NCT of Delhi.

The High Court of Delhi declared that "section 377 IPC, insofar it criminalises consensual sexual acts of adults in private, is violative of Article 21, 14 and 15 of the Constitution". The High Court relied on affdavits, FIRs, Judgments and Orders to illustrate misuse of Section 377; they also places reliance on academic literature, scientific and medical literature, international law, constituent assembly debates, comparative jurisdictions and judgments of superior courts in India.

The High Court held that the right to life cannot be restricted by what the majority thinks and that section 377 violates the right to dignity and privacy guaranteed under Article 21. The court further held that no one can be discriminated on the basis of their sexual orientation and that the provision is violation of right to equality.

The Supreme Court reversed the judgment of the Delhi High Court and held that section 377 does not violate the constitution and is therefore valid. The Supreme Court reasoned its judgment on several grounds. First, it held that all laws enacted by Parliament are presumed to be valid under the Constitution. This means that in order to hold a law to be invalid, it must be shown, through evidence, that the law is violating the Constitution. The Supreme Court held that there is not enough evidence to show that S.377 IPC is invalid under the Constitution. The Court held that there is very little evidence to show that the provision is being misused by the police. Also, just because the police may be misusing a law, does not automatically mean that the law is invalid. There must be something in the nature of the law itself that is unconstitutional.

According to the Supreme Court, the law can be implemented without misuse.

It was also argued before the Supreme Court that because S.377 applies to certain sexual conduct, it essentially means that all forms of sexual expression by LGBT people would be unnatural. This would mean that any sexual conduct by such people would be illegal. Therefore, S.377 prohibits all sexual expression of LGBT persons. The Supreme Court disagreed with this argument and held that S.377 speaks only of sexual acts and does not speak about sexual orientation or gender identity. This would mean that even heterosexuals indulging in acts covered under S.377 would be punished. Therefore, the section does not target LGBT persons as a class.

[ LGBT = Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals, Transgenders ]

Further, the Supreme Court held that the Delhi High Court in its anxiety to uphold the so called rights of LGBT persons had relied on cases from other countries. They are of the opinion that cases from other countries cannot be directly used in the context of India. Therefore, important cases from South Africa, Fiji, Nepal, USA etc. where homosexuality was decriminalized was not taken into account by the Supreme Court.

Laws are presumed to be valid therefore the responsibility of changing laws is with the parliament. In this case also parliament is free to consider deleting or changing section 377. The Supreme Court also said that despite so many years the Parliament has not changed the law in spite of having ample opportunities to do so. In light of the above factors considered, the Supreme Court reversed the decision of the Delhi High Court and upheld section 377.

section 377

- On 24 August 2017, the Supreme Court upheld the right to privacy (9-0 verdict) as a fundamental right under the Constitution in the landmark Puttaswamy judgement.

- The Court called for equality and condemned discrimination, stating that the protection of sexual orientation lies at the core of the fundamental rights and that the rights of the LGBT population are real and founded on constitutional doctrine.

- This judgement meant that Section 377 was unconstitutional.

- In January 2018, the Supreme Court agreed to hear a petition to revisit the 2013 Naz Foundation judgment. On 6 September 2018, the Court ruled unanimously in Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India that Section 377 was unconstitutional "in so far as it criminalises consensual sexual conduct between adults of the same sex". A long battle drew to an end!