Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - begin learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

Important legislations after Independence

1.0 RIGHT TO INFORMATION ACT

1.1 The campaign for right to information

Objections to the Official Secrets Act have been raised since 1948, when the Press Laws Enquiry Committee recommended certain amendments. In 1977, the government formed a working group to look into the possibilities of amending the Official Secrets Act. Unfortunately, the working group did not recommend changes, as it felt the Act related to the protection of national safety and did not prevent the release of information in the public interest, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. In 1989, a committee was set up which recommended limiting the areas where government information could be hidden, and opening up all other spheres of information. However, no legislation followed from these recommendations.

It's taken India 77 years to transition from the repressive climate of the OSA to one where citizens can demand the right to information. The enactment of the Freedom of Information Act 2002 marks a significant shift for Indian democracy, for the greater the access to information by citizens, the greater the responsiveness of government to community needs.

In the early 1990s, in the course of the struggle of the rural poor in Rajasthan, the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) hit upon a novel way to demonstrate the importance of information in an individual's life through public hearings, or jan sunwais. The MKSS's campaign demanded transparency of official records, a social audit of government spending, and a redressal machinery for people who had not been given their due. The campaign caught the imagination of a large cross-section of people, including activists, civil servants and lawyers.

The National Campaign for People's Right to Information (NCPRI), formed in the late-1990s, became a broad-based platform for action. As the campaign gathered momentum, it became clear that the right to information had to be legally enforceable. As a result of this struggle, not only did Rajasthan pass a law on the right to information, but, in a number of panchayats, graft was exposed and officials punished.

The Press Council of India drew up the first major draft legislation on the right to information, in 1996. The draft affirmed the right of every citizen to information from any public body. Significantly, the term 'public body' included not only the State but also all privately-owned undertakings, non-statutory authorities, companies, and other bodies whose activities affect the public interest. Information that cannot be denied to Parliament or state legislatures cannot be denied to a citizen either. The draft also provided for penalty clauses for defaulting authorities.

Next came the Consumer Education Research Council (CERC) draft-by far the most detailed proposed freedom of information legislation in India. In line with international standards, it gave the right to information to anyone, except "alien enemies", whether or not they were citizens.

It required public agencies at the federal and state levels to maintain their records in good order, to provide a directory of all records under their control, to promote the computerisation of records in interconnected networks, to publish all laws, regulations, guidelines, circulars related to or issued by government departments, and any information concerning welfare schemes. The draft provided for the outright repeal of the OSA. This draft didn't make it through Parliament either.

Finally, in 1997, a conference of chief ministers resolved that the central and state governments would work together on transparency and the right to information. Following this, the Centre agreed to take immediate steps, in consultation with the states, to introduce freedom of information legislation, along with amendments to the Official Secrets Act and the Indian Evidence Act, before the end of 1997. Central and state governments also agreed to a number of other measures to promote openness, including establishing accessible computerised information centres to provide information to the public on essential services, and speeding up ongoing efforts to computerise government operations.

1.2 The RTI Act, 2005

Parliament of India enacted the Right to Information Act, 2005 by repealing the Freedom of Information Act, 2002 in order to ensure greater and more effective access to information under the control of Public Authorities in order to promote transparency and accountability in the working of every public authority. The key objectives of the Act are, viz., appointment of public information officers in each office, establishment of an appellate machinery with investigating powers to review decisions of the public information officers, penal provisions for failure to provide information as per Law, provisions to ensure maximum disclosure and minimum exemptions, an effective mechanism for access to information by the authorities.

1.2.1 Salient features of The Right to Information Act, 2005

- Statutory provisions made for right to information

- All citizens possess the right to information

- Information includes any mode of information in any form of record, document, e-mail, circular, press release, contract, sample or electronic data, etc.

- Rights to information covers inspection of work, document, record and its certified copy and information in form of diskettes, floppies, tapes, video cassettes in any electronic mode or stored-informations in computers, etc.

- Information can be obtained within 30 days from the date of request in a normal case

- If information is a matter of life or liberty of a person, it can be obtained within 48 hours from time of request

- Every public authority is under obligation to provide information on written request or request by electronic means. Certain informations are prohibited

- Restrictions made for third party information

- Appeal against the decision of the Central Information Commission or State Information Commission can be made to an officer who is senior in rank

- Penalty for refusal to receive an application for information or for not providing information is Rs.250/- per day but the total amount of penalty should not exceed Rs.25,000/-

- Central Information Commission and State Information Commission are to be constituted by the Central Government and the respective State Governments

- No Court can entertain any suit, application or other proceedings in respect of any order made under the Act

1.3 Important state initiatives

Inspired and encouraged by the exercises taken up by the central government, many state governments yielded under popular pressure and prepared draft legislations on the right to information. A number of states introduced their own transparency legislations before the Freedom of Information Bill was finally introduced in the Lok Sabha on July 25, 2000.

Goa: One of the earliest and most progressive legislations, it had the fewest categories of exceptions, provision for urgent processing of requests pertaining to life and liberty, and a penalty clause. It also applied to private bodies executing government works. One weakness was that it had no provision for pro-active disclosure by government.

Tamil Nadu: The legislation stipulated that authorities must part with information within 30 days of it being sought. Following this legislation, all public distribution system (PDS) shops in the state were asked to display details of stocks available. All government departments also brought out citizens charters listing information on what the public was entitled to know and get.

Karnataka: The right to information legislation contained standard exception clauses covering 12 categories of information. It had limited provisions for pro-active disclosure, contained a penalty clause, and provided for an appeal to an independent tribunal.

Delhi: This law was along the lines of the Goa Act, containing standard exceptions and providing for an appeal to an independent body, as well as the establishment of an advisory body, the State Council for Right to Information. Residents of the capital can seek any type of information with some exceptions from the civic body, after paying a nominal fee. It was also clearly stated that if the information was found to be false, or had been deliberately tampered with, the official could face a penalty of Rs 1,000 per application.

Rajasthan: After five years of dithering, the Right to Information Act was passed in 2000. The movement was initiated at the grassroots level. Village-based public hearings, jan sunwais, organised by the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS), gave space and opportunity to the rural poor to articulate their priorities and suggest changes. The four formal demands that emerged from these jan sunwais were: 1) Transparency of panchayat functioning; 2) accountability of officials; 3) social audit; and 4) redressal of grievances. The Bill when it was eventually passed, however, placed at least 19 restrictions on the right of access to information. Besides having weak penalty provisions, it gave too much discretionary power to bureaucrats. Despite this, the right to information movement thrived at the grassroots level in Rajasthan, following systematic campaigns waged by concerned groups and growing awareness about the people's role in participatory governance. It was the jan sunwais that exposed the corruption in several panchayats and also campaigned extensively for the right to food after the revelation of hunger and starvation-related deaths in drought-ravaged districts.

Maharashtra: The Maharashtra assembly passed the Maharashtra Right to Information (RTI) Bill in 2002, following sustained pressure from social activist and anti-corruption crusader Anna Hazare. The Maharashtra legislation was the most progressive of its kind. The Act brought not only government and semi-government bodies within its purview but also state public sector units, cooperatives, registered societies (including educational institutions) and public trusts. Public information officers who failed to perform their duties could be fined up to Rs 250 for each day's delay in furnishing information. Where an information officer had wilfully provided incorrect and misleading information, or information that was incomplete, the appellate authority hearing the matter could impose a fine of up to Rs 2,000. The information officer concerned could also be subject to internal disciplinary action. The Act even provided for the setting up of a council to monitor the workings of the Act. The council comprised senior members of government, members of the press, and representatives of NGOs. They were expected to review the functioning of the Act at least once every six months.

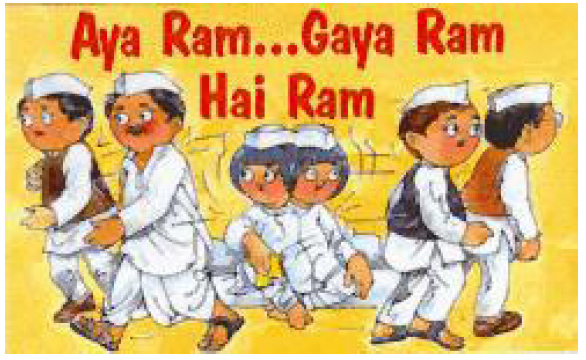

2.0 ANTI DEFECTION LAW IN INDIA

By the 52nd Amendment, the Tenth Schedule was included in the Constitution in 1985 by the Rajiv Gandhi ministry. This set the provisions for disqualification of elected members on the grounds of defection to another political party. This law today is called the Anti Defection Law.

The grounds for disqualification under this law are

- If an elected member voluntarily gives up his membership of a political party;

- If he votes or abstains from voting in such House contrary to any direction issued by his political party or anyone authorized to do so, without obtaining prior permission.

As a pre-condition for his disqualification, his abstention from voting should not be condoned by his party or the authorized person within 15 days of such incident.

2.1 Loopholes in the Act

As per the 1985 Act, a 'defection' by one-third of the elected members of a political party was considered a 'merger'. Such defections were not actionable against. The Dinesh Goswami Committee on Electoral Reforms, the Law Commission in its report on "Reform of Electoral Laws" and the National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution (NCRWC) all recommended the deletion of the Tenth Schedule provision regarding exemption from disqualification in case of a split.

Finally the 91st Constitutional Amendment Act, 2003, changed this. So now at least two-thirds of the members of a party have to be in favour of a "merger" for it to have validity in the eyes of the law. "The merger of the original political party or a member of a House shall be deemed to have taken place if, and only if, not less than two-thirds of the members of the legislature party concerned have agreed to such merger," states the Tenth Schedule.

A split in a political party will not be considered a defection if an entire political party merges with another; if a new political party is formed by some of the elected members of one party; if he or she or other members of the party have not accepted the merger between the two parties and opted to function as a separate group from the time of such a merger.

The whip upholds the party directives in the House as the authorised voice of the party. On defection of elected members of his party, the whip can send a petition on the alleged defection to the Chairman or the Speaker of a House for their disqualification. He can also expel the members from the party.

But this does not necessarily mean that the members so expelled lose their seats in the House. They continue to hang on to their seats as long as the Chairman or the Speaker of a House gives a final decision on their disqualification from the House after a proper enquiry on the basis of the petition filed by the party whip.

2.2 Options before a disqualified elected member

The members so disqualified can stand for elections from any political party for a seat in the same House. But they naturally cannot get a ticket from his former party. The decision on questions as to disqualification on ground of defection are referred to the Chairman or the Speaker of such House and his decision is final. All proceedings in relation to any question on disqualification of a member of a House under this Schedule are deemed to be proceedings in Parliament or in the Legislature of a state. No court has any jurisdiction.

3.0 THE MUSLIM WOMEN (PROTECTION OF RIGHTS ON DIVORCE) ACT

The Act was enacted in 1986 in the wake of the Supreme Court's judgment in the famous Shah Bano case, whereby the apex court ruled that even a Muslim woman was entitled to receive alimony under the general provisions of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), like anybody else. While the judgment was not the first granting a divorced Muslim woman maintenance under the CrPC, it was the first in which the Supreme Court referred to Muslim personal laws in detail. Many Muslim clerics saw the judgment as an encroachment on the right of Muslims to be governed by their personal laws. Following severe protests from various Muslim community leaders, the Rajiv Gandhi government got the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act passed in Parliament, with absolute majority. Rajiv drew much criticism over the move, with the Opposition calling it another act of "appeasement" towards the minority community by the Congress.

3.1 Salient features

The Act entitles a divorced Muslim woman to four rights under its specific provisions:

- Right to maintenance during the period of iddat (or iddah, the stipulated waiting period after the divorce in which a woman cannot remarry);

- Right to fair and reasonable provisions for her entire life;

- Right to receive alimony for the child till two years from divorce;

- Right to receive maintenance from the State Wakf Board in some exceptional circumstances.

Diluting the Supreme Court judgment, the most controversial provision of the Act was that it allowed maintenance to a divorced woman only during the period of iddat, or till 90 days after the divorce, according to the provisions of Islamic law. This was in stark contrast to Section 125 of the CrPC - the general provision for maintenance of wives, children and parents - that applies to everyone irrespective of religion.

The apex court has interpreted the provisions of the Act more liberally. In Daniel Latifi vs Union of India, 2001, the Supreme Court upheld the Act in so far as it confined the time period of maintenance to the iddat period. But it also held that the quantum of maintenance must be "reasonable and fair" and therefore last her a lifetime. In effect, the judgment does a balancing act between the effect of the Shah Bano judgment and the words of the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act.

3.2 Uses of the Act

Despite its unique feature of no ceiling on quantum of maintenance, the statute is sparingly used because of the lack of its knowledge even among lawyers. The legal fraternity generally uses the CrPC provision while moving maintenance petitions, considering it handy.

4.0 DOMESTIC VIOLENCE ACT

Domestic violence, also known as domestic abuse, spousal abuse, or intimate partner violence (IPV), can be broadly defined a pattern of abusive behaviours by one or both partners in an intimate relationship such as marriage, dating, family, friends or cohabitation. Domestic violence has many forms including physical aggression (hitting, kicking, biting, shoving, restraining, throwing objects), or threats thereof; sexual abuse; emotional abuse; controlling or domineering; intimidation; stalking; passive/covert abuse (e.g., neglect); and economic deprivation. Domestic violence may or may not constitute a crime, depending on local statues, severity and duration of specific acts, and other variables.

4.1 Forms of domestic violence

All forms of domestic abuse have one purpose: to gain and maintain total control over the victim. Abusers use many tactics to exert power over their spouse or partner: dominance, humiliation, isolation, threats, intimidation, denial and blame.

Direct physical violence ranging from unwanted physical contact to rape and murder. Indirect physical violence may include destruction of objects, striking or throwing objects near the victim, or harm to pets.

Mental or emotional abuse including verbal threats of physical violence to the victim, the self, or others including children, and verbal violence including threats, insults, put-downs, and attacks.

Nonverbal threats may include gestures, facial expressions, and body postures.

Psychological abuse may also involve economic and/or social control such as controlling the victim's money and other economic resources, preventing the victim from seeing friends and relatives, actively sabotaging the victim's social relationships, and isolating the victim from social contacts.

Physical violence: Physical violence is the intentional use of physical force with the potential for causing injury, harm, disability, or death, for example, hitting, shoving, biting, restraint, kicking, or use of a weapon.

Sexual abuse: Sexual abuse is common in abusive relationships. The National Coalition against Domestic Violence reports that between one-third and one-half of all battered women are raped by their partners at least once during their relationship. Any situation in which force is used to obtain participation in unwanted, unsafe, or degrading sexual activity constitutes sexual abuse. Forced sex, even by a spouse or intimate partner with whom consensual sex has occurred, is an act of aggression and violence. Furthermore, women whose partners abuse them physically and sexually are at a higher risk of being seriously injured or killed.

Emotional abuse: Emotional abuse (also called psychological abuse or mental abuse) can include humiliating the victim privately or publicly, controlling what the victim can and cannot do, withholding information from the victim, deliberately doing something to make the victim feel diminished or embarrassed, isolating the victim from friends and family, implicitly blackmailing the victim by harming others when the victim expresses independence or happiness, or denying the victim access to money or other basic resources and necessities.

People who are being emotionally abused often feel as if they do not own themselves; rather, they may feel that their significant other has nearly total control over them. Women or men undergoing emotional abuse often suffer from depression, which puts them at increased risk for suicide, eating disorders, and drug and alcohol abuse.

Economic abuse: Economic abuse is when the abuser has complete control over the victim's money and other economic resources. Usually, this involves putting the victim on a strict "allowance", withholding money at will and forcing the victim to beg for the money until the abuser gives them some money. It is common for the victim to receive less money as the abuse continues. This also includes (but is not limited to) preventing the victim from finishing education or obtaining employment, or intentionally squandering or misusing communal resources.

Stalking: Stalking is often considered a type of psychological intimidation that causes a victim to feel a high level of fear. Many cases are heard of in which girls/women report losing their confidence when boys or men stalk them on the streets. Some even give up their jobs, or altogether stop moving out of the homes.

Domestic Violence Act, 2005, hereinafter referred at Protection for Women against Domestic Violence (PWDVA), has been passed with a view to improve the position of women in the domestic front. The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act 2005 (DVA) came into force 26.10.2006. It is widely expected that DVA will go a long way to provide relief to women from domestic violence and enforce their 'right to live'. Primarily DVA is meant to provide protection to the wife or female live-in partner from violence at the hands of husband or male live-in partner or relatives. DVA also extends its protection to women who are sisters, widows or mothers.

4.2 Main features of the Act

The main Features of the Act are as follows:

- The definition of an 'aggrieved person' is equally wide and covers not just the wife but a woman who is the sexual partner of the male irrespective of whether she is his legal wife or not. The daughter, mother, sister, child (male or female), widowed relative, in fact, any woman residing in the household who is related in some way to the respondent, is also covered by the Act.

- The respondent under the definition given in the Act is "any male, adult person who is, or has been, in a domestic relationship with the aggrieved person" but so that his mother, sister and other relatives do not go scot free, the case can also be filed against relatives of the husband or male partner [Chapter I - Sec.2(a)]

- The information regarding an act or acts of domestic violence does not necessarily have to be lodged by the aggrieved party but by "any person who has reason to believe that" such an act has been or is being committed. Which means that neighbours, social workers, relatives etc. can all take initiative on behalf of the victim. [ Chapter III - Sec. 4]

- This fear of being driven out of the house effectively silenced many women and made them silent sufferers. The court, by this new Act, can now order that she not only reside in the same house but that a part of the house can even be allotted to her for her personal use even if she has no legal claim or share in the property. [Chapter IV - Sec. 17]

- Section 18 of the same chapter allows the magistrate to protect the woman from acts of violence or even "acts that are likely to take place" in the future and can prohibit the respondent from dispossessing the aggrieved person or in any other manner disturbing her possessions, entering the aggrieved person's place of work or, if the aggrieved person is a child, the school.

- The respondent can also be restrained from attempting to communicate in any form, whatsoever, with the aggrieved person, including personal, oral, written, electronic or telephonic contact . The respondent can even be prohibited from entering the room/area/house that is allotted to her by the court.

- The Act allows magistrates to impose monetary relief and monthly payments of maintenance. The respondent can also be made to meet the expenses incurred and losses suffered by the aggrieved person and any child of the aggrieved person as a result of domestic violence and can also cover loss of earnings, medical expenses, loss or damage to property and can also cover the maintenance of the victim and her children.

- Section 22 allows the magistrate to make the respondent pay compensation and damages for injuries including mental torture and emotional distress caused by acts of domestic violence.

- Section.31 gives a penalty up to one year imprisonment and/or a fine up to Rs. 20,000/- for and offence. The offence is also considered cognisable and non-bailable.

- Section 32 (2) goes even further and says that "under the sole testimony of the aggrieved person, the court may conclude that an offence has been committed by the accused"

- The Act also ensures speedy justice as the court has to start proceedings and have the first hearing within 3 days of the complaint being filed in court and every case must be disposed of within a period of sixty days of the first hearing.

- It makes provisions for the state to provide for Protection Officers and the whole machinery by which to implement the Act.

- The act enuciates the certain duties of central and state government to make wide publicity & training programs for the police officers.

- The Act also provides for the assistance of welfare experts if found necessary by the Magistrate.

- The Act also provides for the penalty for not discharging duty of Protection Officer.

4.3 Loopholes in the present system

Un-clarified responsibility and un-sufficient official resource: According to the Domestic Violence Act, Protection Officer has the duty to make domestic incident reports (DIR) in prescribed form and make application to Magistrate. Also, service providers have the power to record the DIR if the aggrieved person desires so. In practice, after two years of implementation, duty of each role still seems ambiguous. In the consultation on Domestic Violence Act and Reproductive Rights (29th-30th Nov.2008), advocators around India expressed their worry about the un-specialized of Protection Officers.

Lack of training of Police Officers and Magistrates: Numerous advocates pointed to the lack of training of police officers and magistrates regarding the Act's requirements and its purpose, as well as a lack of sensitivity training towards the issue of domestic violence, an old evil but newly recognized concept in Indian society. This lack of training has led to the re-victimization of women within the justice system, either through police non-response to calls for help, sending women back home to their abusers by branding their victimization as mere domestic disputes, or magistrates allowing for numerous continuances of cases, prolonging the court process and forcing victims to come to court to face their trauma time and again.

Dual system (Family Court and Criminal Court): There are mainly two legal approaches for women who had suffered domestic violence, one is filing for divorce through Family Court, and the other is filing application to Magistrate according to DV Act which might go through Criminal Legal System. The dual system sometimes makes the legal proceeding more complex even tedious for them. Also, the social impression of each approach put some stress on them.

Misled as a one-way affair:The act is deeply controversial due to its insistence that firstly, the person who commits domestic violence is always a male, and secondly, that on being accused, the onus is on the man to prove his innocence. Therefore there are a lot of chances of the act being misused by unscrupulous women.

Overweening ambition and lack of proportion: In attempting to anticipate all possible ways to protect all aggrieved women from any sort of harm, the framers of the law have put their faith in all women being essentially honest victims, without worrying about proof of claims. In the process we are likely to see this law make a mockery of itself.

Disparities in implementation: There are major disparities in implementation of the law in various states. For instance, while Maharashtra appointed 3,687 protection officers, Assam had only 27 on its rolls, and Gujarat 25. Andhra Pradesh had an allocation of Rs 100 million for implementation of the PWDVA, while other states like Orissa lagged far behind. Not surprisingly, states that invested in implementation of the Act in terms of funds and personnel also reported the highest number of cases filed. Maharashtra filed 2,751 cases between July 2007 and August 2008 while Orissa could only manage 64 cases between October 2006 and August 2008.

Public opposition: The report highlights the problem of public opposition. Many have labelled the PWDVA (Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act) as a law that propagates inequality. There are, at the moment, five petitions challenging the PWDVA in various high courts which argue that the Act violates the constitutional right to equality as it provides relief only to women. Till date, a judgment has been delivered only in one case (Aruna Pramod Shah vs Union of India) by the Delhi High Court.

Fading attempts of NGOs as service providers: Very few NGO's have registered themselves as service providers under the Act, the registered service providers as well as protection officers' lack experience with domestic violence work, too few protection officers are assigned in each district to handle the caseload, and government service providers provide poor services to those in need.

Failure to mandate criminal penalties: Advocates and protection officers have noted additional inadequacies of the PWDVA, including the Act's failure to mandate criminal penalties for abuse along with its civil measures, its failure to explicitly provide a maximum duration of appellate hearings which delays women's grant of relief, the residency orders' failure to give women substantive property rights to the shared household (only giving them the right to reside there), and a basic lack of infrastructure linking law enforcement officials, officials under the act, and service providers together in order to best and most efficiently serve domestic violence victims.

Shaking responsibilities: The act has by and large affected those who have access to quality legal aid. Though the Act provides for state legal aid, the quality of services in such cases is really poor. The state has passed on all responsibility to the service providers. They have to provide medical aid to abused women, arrange for short stay homes and arrange for compensation. It becomes a burden on these providers who do not have the wherewithal.

Lack of follow up: Needless to say, lack of follow up can endanger victims' safety as well as allow for corruption and inefficiency within the organizations intended to help them. In addition, a Times of India July 19th, 2009 article reported the PWDVA's lack of retroactivity, citing the Mumbai High Court's decision to set aside an order permitting an abused woman to reside in her husband's flat since his eviction attempt occurred prior to the PWDVA's enactment in 2005.

5.0 SCHEDULED CASTES AND TRIBES (PREVENTION OF ATROCITIES) ACT 1989

Enacted in 1989, the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act was aimed at preventing commission of crimes and atrocities against members of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes, especially by influential persons belonging to the upper castes. It also provides for setting up of Special Courts for speedy trial of cases under the Act and for relief and rehabilitation of the victims of offences under the Act. However, members of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes can't be booked under the Act.

5.1 Kinds of offences

Any person, either an individual or a government servant, can be booked under the Act if he threatens, humiliates, injures, abuses verbally or physically, wrongfully confines or calls by his caste a member of the Scheduled Castes or the Scheduled Tribes notified under the Constitution. For example, if a member of the upper caste tries to force a member of the SC or ST caste to drink or eat something against his wish or tries to dispossess him from his land, he can be booked under the Act. Forcing a SC/ST citizen to work for free or vote in favour of a candidate in an election against his choice is also an offence punishable under the Act. Similarly, government servants can be booked under the Act if they fail to discharge their duty to protect the rights of members of the SC/ST.

5.2 Punishments

The minimum punishment under the Act is six months and fine, but in cases where the offence is also punishable under the Indian Penal Code, the maximum punishment can extend upto life plus fine. The quantum of punishment for anybody who is punished under the Act for the second time is more. The court while awarding the punishment can also order attachment or forfeiture of any movable or immovable property of the accused.

5.3 Other provisions

For every Special Court established by the state government, it can also appoint an advocate who has been in practice for not less than seven years as special public prosecutor. A District Magistrate or any other designated officer, if he has reason to believe that a person or a group of persons is likely to commit an offence or has threatened to commit any offence under this Act, can take necessary action.

5.4 Recent cases

The general consensus seems to be that the Act has not done much to prevent harassment of members of the SC/ST castes. As per the annual report of the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment (SJE) for 2002, of the total cases filed, only 21.72 per cent were disposed of. Out of these, 2.31 per cent ended up in conviction. Even the Supreme Court has pointed to this anomaly. Last year, a PIL was filed in the Allahabad High Court, alleging that offences committed against members of the SCs and STs in Uttar Pradesh were not being taken cognisance of under the Act. Uttar Pradesh, incidentally, has the highest number of cases under the Act. Last year, the present BSP government had issued an order that said action would be taken under Section 182 of the IPC against those who lodge false cases under the Act. The Section 182 of the IPC provides for imprisonment upto six months or fine up to Rs 1,000 or both for a person or persons who give false information with intent to cause public servant to use his lawful power to the injury of another person.

Recently, a Congress MP in Andhra Pradesh threatened a bank manager belonging to a forward caste that he would file a SC/ST atrocity case against him. The reason for the MP's anger was that the bank manager, whom he also slapped, had not done some work that his constituents wanted him to do.

In 2012, the Mayor of Varanasi was booked under the Act, following which residents of the town took to the streets to protest.

In May 2013, a case under the Act was filed against Pramod Jaiswal, younger brother of Union Coal Minister Sriprakash Jaiswal. The minister's brother was accused of harassing his servants.

6.0 THE PROTECTION OF CHILDREN FROM SEXUAL OFFENCES (POCSO) ACT 2012

India is home to the largest child population in the world, with almost 42 per cent of the total population under eighteen years of age. Needless to say, the health and security of the country's children is integral to any vision for its progress and development. One of the issues marring this vision for the country's future generations is the evil of child sexual abuse. Statistics released by the National Crime Records Bureau reveal that there has been a steady increase in sexual crimes against children.

According to a study conducted by the Ministry of Women and Child Development in 2007, over half of the children surveyed reported having faced some form of sexual abuse, with their suffering exacerbated by the lack of specific legislation to provide remedies for these crimes.

While rape is considered a serious offence under the Indian Penal Code, the law was deficient in recognising and punishing other sexual offences, such as sexual harassment, stalking, and child pornography, for which prosecutors had to rely on imprecise provisions such as "outraging the modesty of a woman".

The Ministry of Women and Child Development, recognising that the problem of child sexual abuse needs to be addressed through less ambiguous and more stringent legal provisions, championed the introduction of a specific law to address this offence.

The Act defines a child as any person below eighteen years of age, and regards the best interests and well being of the child as being of paramount importance at every stage, to ensure the healthy physical, emotional, intellectual and social development of the child.

Different forms of sexual abuse: It defines different forms of sexual abuse, including penetrative and non-penetrative assault, as well as sexual harassment and pornography

When sexual abuse will be considered to be aggravated: It deems a sexual assault to be "aggravated" under certain circumstances, such as when the abused child is mentally ill or when the abuse is committed by a person in a position of trust or authority vis-a-vis the child, like a family member, police officer, teacher, or doctor.

People who traffick children for sexual purposes are also punishable under the provisions relating to abetment in the Act.

Graded punishment: The Act prescribes stringent punishment graded as per the gravity of the offence, with a maximum term of rigorous imprisonment for life, and fine.

Mandatory reporting:

- In keeping with the best international child protection standards, the Act also provides for mandatory reporting of sexual offences.

- This casts a legal duty upon a person who has knowledge that a child has been sexually abused to report the offence;

- if he fails to do so, he may be punished with six months' imprisonment and/ or a fine. Thus, a teacher who is aware that one of her students has been sexually abused by a colleague is legally obliged to bring the matter to the attention of the authorities.

For providing false information:

- The Act, on the other hand, also prescribes punishment for a person, if he provides false information with the intention to defame any person, including the child.

Police as child protectors:

- The Act also casts the police in the role of child protectors during the investigative process. Thus, the police personnel receiving a report of sexual abuse of a child are given the responsibility of making urgent arrangements for the care and protection of the child, such as obtaining emergency medical treatment for the child and placing the child in a shelter home, should the need arise.

Child welfare committee:

- The police are also required to bring the matter to the attention of the Child Welfare Committee (CWC) within 24 hours of receiving the report, so the CWC may then proceed where required to make further arrangements for the safety and security of the child.

Examination of the victim:

- The Act also makes provisions for the medical examination of the child designed to cause as little distress as possible. The examination is to be carried out in the presence of the parent or other person whom the child trusts, and in the case of a female child, by a female doctor.

- The Act further makes provisions for avoiding the re-victimisation of the child at the hands of the judicial system.

Constitution of special courts:

- It provides for special courts that conduct the trial in-camera and without revealing the identity of the child, in a manner that is as child-friendly as possible.

- Hence, the child may have a parent or other trusted person present at the time of testifying and can call for assistance from an interpreter, special educator, or other professional while giving evidence; further, the child is not to be called repeatedly to testify in court and may testify through video-link rather than in the intimidating environs of a courtroom.

- Above all, the Act stipulates that a case of child sexual abuse must be disposed of within one year from the date the offence is reported.

- Another important provision in the Act is that it provides for the Special Court to determine the amount of compensation to be paid to a child who has been sexually abused, so that this money can then be used for the child's medical treatment and rehabilitation.

Legal Provisions for Women and Children

Laws relating to women

- Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987

- Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 1983

- Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961

- Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956

- Indecent Representation of Women (Prohibition) Act, 1986

- National Commission for Women Act, 1990

- Prohbn of Sexual Harassment of Women at the Workplace Bill, 2010

- Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005

Laws relating to marriage & divorce

- Anand Marriage Act, 1909

- Arya Marriage Validation Act, 1937

- Births, Deaths & Marriages Registration Act, 1886

- Bangalore Marriages Validating Act, 1936

- Converts’ Marriage Dissolution Act, 1866

- Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act, 1939

- Family Courts Act, 1984

- Foreign Marriage Act, 1969

- Hindu Marriage Act, 1955

- Hindu Marriages (Validation of Proceedings) Act, 1960

- Indian Christian Marriage Act, 1872

- Indian Divorce Act, 1869

- Indian Divorce Amendment Bill, 2001

- Indian Matrimonial Causes (War Marriages) Act, 1948

- Marriage Laws (Amendment) Act, 2001

- Marriages Validation Act, 1892

- Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986

- Parsi Marriage & Divorce Act, 1936

- Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006

- Special Marriages Act, 1954

Laws relating to working women

- Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1976

- Employees State Insurance Act, 1948

- Equal Remuneration Act, 1976

- Factories (Amendment) Act, 1948

- Maternity Benefit Act, 1961 (Amended in 1995)

- Plantation Labour Act, 1951

Laws relating to maintenance

- The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973:

- Order for maintenance of wives, children and parents under section 125

- Procedure to be followed under section 125

- Alteration in allowance under section 125

- Enforcement of the order of maintenance

Laws Laws relating to abortion

- Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971

- Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation & Prevention of Misuse) Act, 1994

- Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation & Prevention of Misuse) Amendment Act, 2001

- Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation & Prevention of Misuse) Amendment Act, 2002

Laws relating to property, succession, inheritance, guardianship & adoption

- Guardians & Wards Act, 1890

- Hindu Adoptions & Maintenance Act, 1956

- Hindu Inheritance (Removal of Disabilities) Act, 1928

- Hindu Minority & Guardianship Act, 1956

- Hindu Succession Act, 1956

- Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005

- Indian Succession Act, 1925

- Indian Succession (Amendment) Act, 2002

- Married Women’s Property Act, 1874

- Married Women’s Property (Extension) Act, 1959

Sec-498 A I.P.C. – Its Use And Misuse

Introduction: Most of the people are not aware of the Section 498A of the IPC or what to do when a case related to Section 498A is registered. It is important to know more on what this law is all about. Section 498A was introduced in the year 1983 to protect a married woman from being subjected to cruelty. It claims to provide protection to women against dowry-related harassment and cruelty. On the other hand, it became an easy tool for women to misuse it and wreak revenge from their NRI husbands or to file a false case. Section 498A is one of the most controversial sections of the IPC.

What is Section 498A : Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) deals with the violence done on women after her marriage by her husband or her in-laws or any relative of the husband. It prescribes punishment for 3 years and a fine. It gave a new definition to cruelty. Cruelty can be defined as –

- If the act done is of such a nature that the woman is enticed to commit suicide or cause an injury to herself, which may prove fatal. This was added in the case of Shobha Rani v. Medhukar Reddy. It was held in the case that evidence is required to prove cruelty.

- If the act done is to harass women or any other person related to her to meet unlawful demands.

Need for Section 498A : Women have always been subject to cruelty by male society. Laws like these help women to fight back. Woman feel they are being heard. There is a lot of need for laws like these in a country like India –

- 9 out of 10 cases are always related to dowry. So, there is dire need for these laws to prevent women from the cruelty.

- Woman are continuously forced, tortured, threatened or abused for demand for something or the other. The Section 498A of the IPC helps the woman to approach the court of law and punish the wrongdoer.

- In many cases, the woman are also subject to mental cruelty. There is no law which can help the woman to ease the mental pain caused to her. Acts like these help woman in every possible ways.

- No matter if the laws are misused,they cannot be removed from the Indian Penal Code. As the laws can always be amended. There will be certain loopholes but always a provision can be added to rectify the problems.

The Indian Constitution is using the section 498A to protect married women from cruelty at the matrimonial home. The section was added to IPC to protect women from any domestic violence. Though there is wide misuse by the women. This section is the most fiercely debated section of the IPC. The IPC crimes against women have increased over the years. Most numbers of cases are reported from Delhi, India. A major number of crimes are committed against women every year :

Surely, there is a need for Section 498A because even if there may be misuse, but the actual cases cannot be foregone on this basis. Measures can be taken to overcome the loopholes but entirely scrapping the law can prove to be detrimental to the society.

Misuse of the law : Supreme Court calls the Section 498A as ‘Legal Terrorism’. The misuse or abuse of the law is mostly done by urban and educated women. Also, in most of the cases, the husband and two of his relatives are prosecuted.

- Women use it as a weapon than to shield themselves. In Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar,[2] it was stated that bedridden grandfathers and grandmothers and even relatives living abroad were arrested. So, women have started using it as a weapon to get their husbands arrested if they are not satisfied with them. There are many false cases registered every year, as a result, it increases the pendency of cases in the courts.

- There have been a number of cases when the male is not of India and he comes to India to marry the lady. Due to extortion and fear of jail, he is made to do acts which he otherwise would not have done. He is under the fear of Section 498A.

- Police visit the office premises of men and his reputation is harmed. Police can also pick up the relatives if the complaint is harmed. Also, it does not require any proof before arrest. Even no investigation is required. So, if there is a small dispute woman can use the section to seek revenge.

- Gifts are sometimes misunderstood as dowry. So, this can again pose a problem.

So, pro-women laws should not become anti-man laws.

Past Records : The National Crime Record Bureau releases All India Crime Data every year. The cases registered under Section 498A are increasing every year, though the conviction rate each year is falling. The conviction rate under Section 498A is ¼ of the total crimes conviction rate.

Arguments on the Section 498A : The law can only be invoked by women and her relatives. This proves to be a demerit. The Justice Malimath Committee report says, “The harsh law, far from helping the genuine victimized women, has become a source to blackmail and harassment of husbands and others. Once a complaint (FIR) is lodged with the Police under s.498A/406 IPC, it becomes an easy tool in the hands of the Police to arrest or threaten to arrest the husband and other relatives named in the FIR without even considering the intrinsic worth of the allegations and making a preliminary investigation.”

On the other hand, Section 428A is useful too. This has been the only section which helps the women to fight against the atrocities by man. A woman can file a complaint if she has been subject to any kind of cruelty. The misuse can be curtailed, but the complete scrapping of the article will prove futile. A married woman approaches the court only when she is left with no other option and no remedy. So, the existing law should be there rather than overhyping the misuse point. Also, in the procedure of mediation, the woman may face several threats. So, the section is important.

Grey areas under the Law

The judiciary has always ensured to provide equal rights to women and to protect them. It ensures that women do not get discriminated as it is also mentioned in our Constitution. The government has always been enthusiastic enough to protect the rights of women. Therefore, the government of India formed Domestic laws and section 498A. But there are certain grey areas in it. There are lacunas in the existing law which can hamper the successful implementation of the law. Some of the grey areas are –

- Judiciary acts as an ‘agents of wives’. There are cases in which wives side brutally hit husband and husband’s relatives. The attacks are fatal in nature. But there are no laws on this. The wife has got a free licence to hit the husband and have an easy escape. Also, the judiciary accepts this behaviour as normal.

- Judges do not dismiss the case if the wife does not attend the case proceedings. Even if she does not attend the proceedings for years, the case continues to go on. Also, judges take months and sometimes years to decide upon one bail petition. This makes the men neither free of charge nor lets him live a happy life.

- The Section 498A is non-bailable and a cognizable offence. The judiciary should change it to a bailable and non-cognizable offence. Bails should be granted to the husband so that if the case is filed on false grounds, there is a course of action left.

How can men protect themselves from false allegations : There is more number of women victims than compared to men. But there also cases when men fall prey to false allegations. There are also cases where women in order to demand maintenance after marriage, hides the fact that she is employed and if they fail, they threaten the husband to file false allegations in the courts. There are cases when men, even commit suicide, to which judiciary is responsible. So, men need to protect themselves against these unjust practices as women are not always the victims

- Men need to collect all the evidence and documents - One must collect as many evidence it can prove innocence in the court of law. Indian Judiciary is pro-women, so it may become quite difficult for men to prove the guilt. Men can even keep voice recordings as they can help in the court. Text messages or any conversation which can be claimed as a substantial proof can be kept by the man. Also, if there is any proof which shows that no demands were made by the husband’s side for dowry before and after marriage can prove to be a strong evidence.

- Try to get an anticipatory bail – if you feel that your wife is going to file a false case against you, hire a good criminal lawyer and get an anticipatory bail. This will help you and your family members from getting arrested. This was held in Rajesh Sharma v. Union of India[3], and allowed the men to take anticipatory bail.

- Men also file an FIR case against your wife for false 498A complaint - Though the police in India do not file such cases, if you have full proofs, they will consider filing your case. Draft a complaint by a good criminal defence lawyer, so that the police does not reject it.

- Men can get the FIR quashed by approaching a High Court under Sec 482 of CrPc - Courts are hesitant to quash an FIR which has been filed by police, but if you have substantial evidence to claim your side you can easily get the FIR quashed.

- Man also file a defamation case against your wife for all the lost reputation - Man is a social animal so reputation is very important for him. So, a man can file a case of defamation under Sec 500 of IPC.

- Man also file a damage recovery case under Sec 9 of CPC - If your wife lies that you have physically or economically or emotionally harassed her and all her claims are false, you can file a suit against her, it has no risk involved.

- Also, prove that the wife moved out of the marriage on her own and without any valid reason.

Remember, evidences are everything in court of law. Without evidence, the court may favour the woman but if you want to be proven innocent, start collecting proofs.

- The Government has already formed: Family Welfare committees in every district. The committee will comprise of three members appointed by the District Legal Aid. The committee will be of volunteers, retired officers or any person who may be willing to work. The government should ensure that these committees function properly and there is no corruption involved in the committees. Every received complaint will be looked by these committees. This will also ensure speedy trials for the complaints.

- The government should ensure that no frivolous cases are filed under the section 498A - For that, there should be stringent punishment prescribed by the government. This will help to stop the woman from filing false cases and take it as an easy escape.

- Also, there should be courts which can help for speedy redressals of the complaints - So, the complaints can be disposed of in a better way.

- The power to arrest should only be exercised after meeting certain standards - The police should not be free to arrest anyone solely on the complaint rather there should be standards fixed by the government.

Conclusion :

- Section 498A can prove to be a weapon as well as a shield to a woman. It is necessary for the government to ensure that no false cases are filed and prove it to be a balanced act – both for husband and wife.

- Women’s emancipation is the need of the hour and every measure should be taken to stop harassment and dowry deaths.

- Also, Helpline Number for Women – 1091. The number can be called by the woman incase of emergency and there is a need for urgent help.

- Therefore, the section is much needed for the society though with certain amendments.

“All the strength and succor you want is within you. Do not be afraid.”

Swami Vivekananda.

Section 3 in The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005

Definition of domestic violence - For the purposes of this Act, any act, omission or commission or conduct of the respondent shall constitute domestic violence in case it—

- harms or injures or endangers the health, safety, life, limb or well-being, whether mental or physical, of the aggrieved person or tends to do so and includes causing physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal and emotional abuse and economic abuse; or

- harasses, harms, injures or endangers the aggrieved person with a view to coerce her or any other person related to her to meet any unlawful demand for any dowry or other property or valuable security; or

- has the effect of threatening the aggrieved person or any person related to her by any conduct mentioned in clause (a) or clause (b); or

- otherwise injures or causes harm, whether physical or mental, to the aggrieved person. Explanation I - For the purposes of this section,—

- “physical abuse” means any act or conduct which is of such a nature as to cause bodily pain, harm, or danger to life, limb, or health or impair the health or development of the aggrieved person and includes assault, criminal intimidation and criminal force;

- “sexual abuse” includes any conduct of a sexual nature that abuses, humiliates, degrades or otherwise violates the dignity of woman;

- “verbal and emotional abuse” includes—

- insults, ridicule, humiliation, name calling and insults or ridicule specially with regard to not having a child or a male child; and

- repeated threats to cause physical pain to any person in whom the aggrieved person is interested.

- “economic abuse” includes

- deprivation of all or any economic or financial resources to which the aggrieved person is entitled under any law or custom whether payable under an order of a court or otherwise or which the aggrieved person requires out of necessity including, but not limited to, household necessities for the aggrieved person and her children, if any, stridhan, property, jointly or separately owned by the aggrieved person, payment of rental related to the shared household and maintenance;

- disposal of household effects, any alienation of assets whether movable or immovable, valuables, shares, securities, bonds and the like or other property in which the aggrieved person has an interest or is entitled to use by virtue of the domestic relationship or which may be reasonably required by the aggrieved person or her children or her stridhan or any other property jointly or separately held by the aggrieved person; and

- prohibition or restriction to continued access to resources or facilities which the aggrieved person is entitled to use or enjoy by virtue of the domestic relationship including access to the shared household.

Explanation II - For the purpose of determining whether any act, omission, commission or conduct of the respondent constitutes “domestic violence” under this section, the overall facts and circumstances of the case shall be taken into consideration.

Legal Provisions for Children

Laws relating to children

- Child Labour (Prohibition & Regulation) Act, 1986

- Child Marriage Restraint Act, 1929

- Children Act, 1960

- Children (Pledging of Labour) Act, 1933

- Commissions for the Protection of Child Rights Act, 2005

- Infant Milk Substitutes Act, 1992

- Infant Milk Substitutes Act, 2003

- Infant Milk Substitutes, Feeding Bottles & Infant Foods (Regulation of Production, Supply & Distribution) Act, 1992

- Infant Milk Substitutes, Feeding Bottles & Infant Foods (Regulation of Production, Supply & Distribution) Amendment Act, 2003

- Juvenile Justice (Care & Protection of Children) Act, 2000

- Juvenile Justice (Care & Protection of Children) Amendment Act, 2006

- Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006

- Reformatory Schools Act, 1897

- Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act, 1956

Offences against women and children in the Indian Penal Code

The Indian Penal Code, 1860

- Abandoning of child under 12 years of age

- Adultery

- Assault or criminal force to a woman with intent to outrage her modesty

- Buying minor for purpose of prostitution

- Causing death of quick unborn child by act amounting to culpable homicide

- Causing miscarriage or miscarriage without the woman’s consent

- Cohabitation caused by a man deceitfully inducing a belief of lawful marriage

- Concealment of birth by secret disposal of dead body

- Concealment of former marriage

- Death caused by act done with intent to cause miscarriage

- Dowry death

- Enticing, detaining or taking away with criminal intent a married woman

- Fraudulent marriage ceremony without lawful marriage

- Husband or relative of a husband of a woman subjecting her to cruelty

- Importation of girl from foreign country

- Intercourse by man with his wife during separation

- Intercourse by a member of management or staff of a hospital with any woman in that hospital

- Intercourse by public servant with a woman in his custody

- Intercourse by superintendent of jail, remand home, etc

- Kidnapping, abducting or inducing woman to compel her marriage

- Marriage ceremony fraudulently gone through without lawful marriage

- Marrying again during lifetime of spouse (Also see here)

- Preventing a child from being born alive or causing its death after birth

- Procreation of minor girl

- Rape

- Selling minor for purpose of prostitution

- Word, gesture or act intended to insult the modesty of a woman