Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - being learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

The Aryans and the Vedic civilisation - Part 2

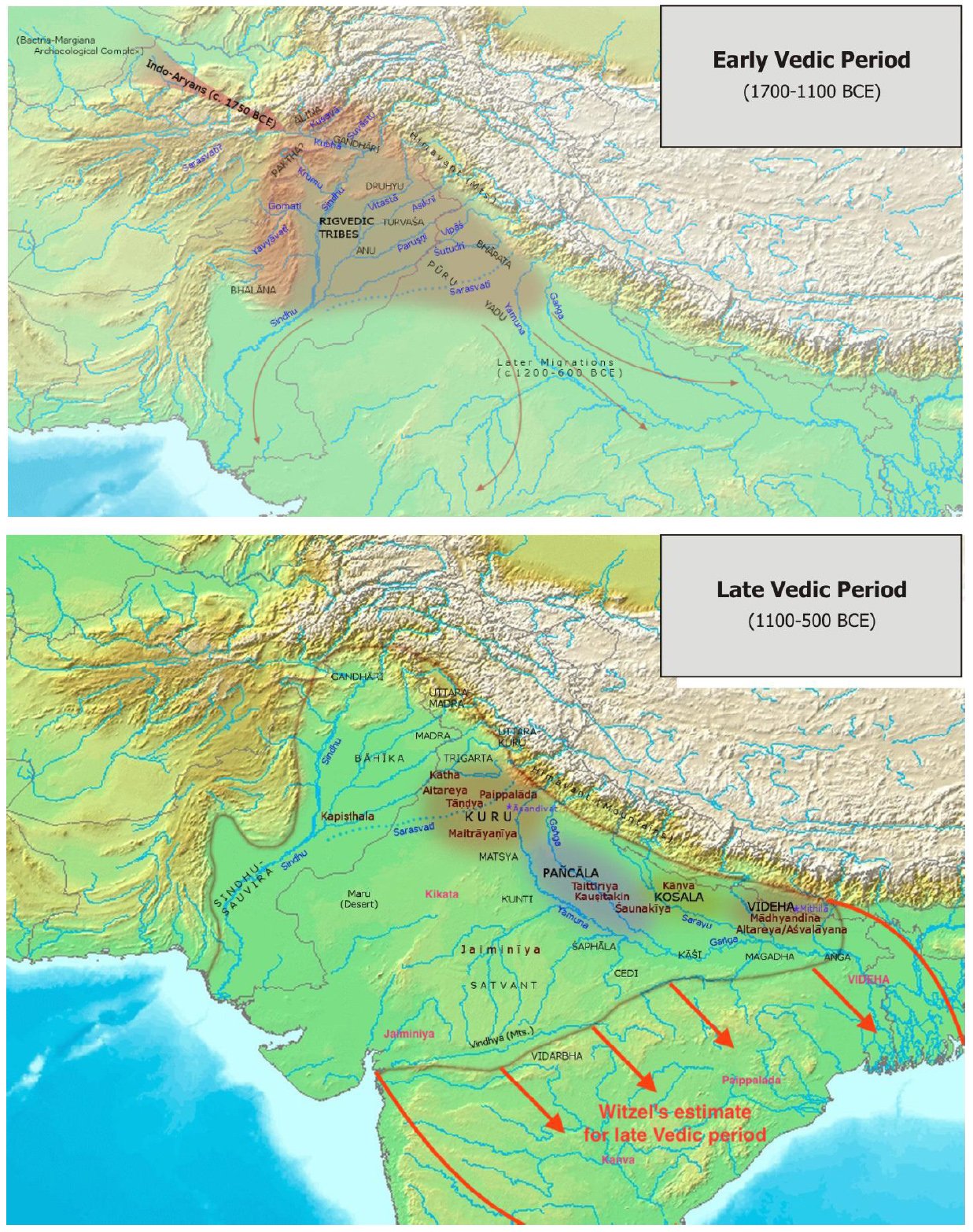

5.0 Expansion in the Later Vedic Period (circa 1000 - 600 B.C.)

The history of the later Vedic period is based mainly on the Vedic texts which were compiled after the age of the Rig Veda. The collections of the Vedic hymns or mantras were known as the Samhitas. The Rig Veda Samhita is the oldest Vedic text, on the basis of which we have described the early Vedic age. For purposes of singing, the prayers of the Rig Veda were set to tune, and this modified collection was known as the Sama Veda Samhita. In addition to the Sama Veda, in post-Rig Vedic times two other collections were composed. These were - the Yajur Veda Samhita and the Atharva Veda Samhita. The Yajur Veda contains not only hymns but also rituals which have to accompany their recitation. The rituals reflect the social and political milieu in which they arose. The Atharva Veda contains charms and spells to ward off evils and diseases. Its contents throw light on the beliefs and practices of the non Aryans. The Vedic Samhitas were followed by the composition of a series of texts known as the Brahmanas. These are full of ritualistic formulae and explain the social and religious meaning of rituals. All these later Vedic texts were compiled in the upper Gangetic basin. in circa 1000-600 B.C. In the same period and in the same area, digging and exploration have brought to light nearly 700 sites inhabited for the first time. These are called Painted Grey Ware (PGW) sites because they were inhabited by people who used earthern bowls and dishes made of painted grey pottery. They also used iron weapons. With the combined evidence from the later Vedic texts and PGW iron-phase archaeology we can form an idea of the life of the people in the first half of the first millennium B.C. in Western Uttar Pradesh and adjoining areas of Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan.

Excavations at Hastinapur, datable to the period 900 B.C. to 500 B.C., have revealed settlements and faint beginnings of town life. But they do not at all answer the description of Hastinapur in the Mahabharata because the epic was finally compiled much later in about the fourth century A.D. when material life had advanced much. In later Vedic times people hardly knew the use of burnt bricks. The mud structures that have been discovered at Hastinapur could not be imposing and lasting. From traditions we learn that Hastinapur was flooded, and the remnants of the Kuru clan moved to Kaushambi near Allahabad.

The Panchala kingdom, which covered the modern districts of Bareilley, Badaun and Farukhabad, is famous for its philosopher kings and Brahmana theologians. Towards the end of the later Vedic period, around 600 B.C., the Vedic people spread from the doab further east to Koshala in eastern Uttar Pradesh and Videha in North Bihar. Although Koshala is associated with the story of Rama, it is not mentioned in Vedic literature. In eastern Uttar Pradesh and North Bihar the Vedic people had to contend against a people who used copper implements and the black-and-red earthern pots. In Western Uttar Pradesh they possibly came up against the people who used pots of ochre or red colour and copper implements. They possibly also encountered thin habitations of some people using black-and-red ware. It is suggested that at a few places they came against the users of the late Harappan culture, but these people seem to represent a conglomerate culture which cannot be characterised as purely Harappan. Whoever be the opponents of the later Vedic peoples evidently they did not occupy any large and compact area and their number in the upper Gangetic basin does not seem to have been large. The Vedic people succeeded in the second phase of their expansion because they used iron weapons and horse-drawn chariots.

Although very few agricultural tools made of iron have been found, undoubtedly agriculture was the chief means of livelihood of the later Vedic people. Later Vedic texts speak of six, eight, twelve and even twenty-four oxen yoked to the plough. This may be an exaggeration. Ploughing was done woth the help of the wooden ploughshare, which would possibly work in the light soil of the upper gangetic plains. Enough bullocks could not be available because of cattle slaughter in sacrifices. Therefore, agriculture was primitive, but there is no doubt about its wide prevalence. The Satapatha Brahmana speaks at length about the ploughing rituals. According to ancient legends, Janaka - the king of Videha and father of Sita, lent his hand to the plough. In those days even kings and princes did not hesitate to take to manual labour. Balarama, the brother of Krishna, is called haladhar or wielder of the plough. In later times ploughing came to be prohibited for the members of the upper Varnas.

The Vedic people continued to produce barley, but during this period rice and wheat became their chief crops. In subsequent times, wheat became the staple food of the people in Punjab and Western Uttar Pradesh. For the first time the Vedic people came to be acquainted with rice in the doab. It is called vrihi in the Vedic texts, and its remains recovered from Hastinapur belong to the eighth century B.C. The use of rice is recommended in rituals, but that of wheat only rarely. Various kinds of lentils were also produced by the later Vedic people.

The later Vedic period saw the rise of diverse arts and crafts. We hear of smiths and smelters, who had certainly to do something with iron working from about 1000 B.C. Numerous copper tools of the pre 1000 B.C. period found in Western Uttar Pradesh and Bihar might suggest the existence of coppersmiths in both Vedic and non-Vedic societies. The Vedic people may have use the copper mines of Khetri in Rajasthan. In any case copper was one of the first metal to be used by the Vedic people. Copper objects have been found in Painted Grey Ware sites. They were used mainly for war and hunting, and also for ornaments.

Weaving was confined to women but was practised on a wide scale. Leather work, pottery, and carpenter's work made great progress. The later Vedic people were acquainted with four types of pottery-black-and-red ware, black-slipped ware, painted grey ware and red ware. The last type of pottery was most popular with them, and has been found almost all over Western Utter Pradesh. However, the most distinctive pottery of the period is known as Painted Grey ware. It consisted of bowls and dishes, which were used either for rituals or for eating or for both, probably by the emerging upper orders. Glass hoards and bangles found in the PGW layer may have been used as prestige objects by few persons. On the whole both Vedic texts and excavations indicate the cultivation of specialized crafts. Jewel-workers are also mentioned in later Vedic texts, and they possibly catered to the needs of the richer sections of society.

Agriculture and various crafts enabled the later Vedic people to lead a settled life. Excavations and explorations give us some idea about settlements in later Vedic times. Widespread Painted Grey Ware sites are found not only in Western Uttar Pradesh and Delhi, which was the Kuru-Panchala area, but also in the adjoining parts of Punjab and Haryana, which was the Madra area and in those of Rajasthan, which was the Matsya area. Altogether we can count nearly 700 sites, mostly belonging to the upper Gangetic basin. Only a few sites such as Hastinapur, Atranjikhera and Noh have been excavated. Since the thickness of the material remains of habitation ranges from one metre to three metres, it seems that these settlements lasted from one to three centuries. Mostly these were entirely new settlements without having any immediate predecessors. People lived in mudbrick houses or in wattle-and-daub houses erected on wooden poles (wattle and daub is a composite building material used for making walls). Although the structures are poor, ovens and cereals (rice) recovered from the sites show that the Painted Grey Ware people, who seem to be the same as the later Vedic people, were agricultural and led a settled life. But since they cultivated with the wooden ploughshare, the peasants could not produce enough for feeding those who were engaged in other occupations. Hence, peasants could not contribute much to the rise of towns.

Although the term nagara is used in later Vedic texts we can trace only the faint beginnings of towns towards the end of the later Vedic period. Hastinapur and Kaushambi (near Allahabad) can be regarded as primitive towns belonging to the end of the Vedic period. They may be called proto-urban sites. The Vedic texts also refer to the seas and sea voyages. This suggests some kind of commerce which may have been stimulated by the rise of new arts and crafts.

On the whole the later Vedic phase registered a great advance in the material life of the people. The pastoral and semi-nomadic forms of living were relegated to the background. Agriculture became the primary source of livelihood, and life became settled and sedentary. Supplemented by diverse arts and crafts the Vedic people now settled down permanently in the upper Gangetic plains. The peasants living in the plains produced enough to maintain themselves, and they could also spare a marginal part of their produce for the support of chiefs, princes and priests.

The formation of wider kingdoms made the chief or the king more powerful. Tribal authority tended to become territorial. Princes ruled over tribes, but their dominant tribes became identical with territories, which might be inhabited by tribes other than their own. In the beginning each area was named after the tribe which settled there first, but eventually the tribal name became current as the territorial name. At first Panchala was the name of a people, and then it became the name of a region. The term rashtra, which indicates territory, first appears in this period.

Traces of the election of the chief or the king appear in later Vedic texts. The one who was considered the best in physical and other qualities was elected raja. He received voluntary presents called bali from his ordinary kinsmen or the common people called the vis. But the chief tried to perpetuate the Right to Receive Presents and enjoy other privileges penaining to his office by making it hereditary in his family; the post generally went to the eldest son. However, this succession was not always smooth. The Mahabharata tells us that Duryodhana, the younger cousin of Yudhishthira, usurped power. For the sake of territory the families of the Pandavas and Kauravas practically destroyed themselves. The Bharata battle shows that kingship knows no kinship.

The king's influence was strengthened by rituals. He performed the rajasuya sacrifice, which was supposed to confer supreme power on him. He performed the ashvamedha, which meant unquestioned control over an area in which the royal horse ran uninterrupted. He also performed the vajapeya or the chariot race, in which the royal chariot was made to win the race against his kinsmen. All these rituals impressed the people with the increasing power and prestige of the king.

During this period collection of taxes and tributes seems to have become common. They were probably deposited with an officer called sangrihitri. The epics tell us that at the time of big sacrifices large-scale distributions were made by the princes and all sections of people were fed sumptuously. In the discharge of his duties the king was assisted by the priest, the commander, the chief queen and a few other high functionaries. At the lower level, the administration was possibly carried on by village assemblies, which may have been controlled by the chiefs of the dominant clans. These assemblies also tried local cases. But even in later Vedic times the king did not possess a standing aimy. Tribal units were mustered in times of war, and according to one ritual for success in war, the king had to eat along with his people (vis) from the same plate.

The prince, who represented the rajanya order, tried to assert his power over all the three other varna. According to the Aitareya Brahmana, a text of the later Vedic period, in relation to the prince, the brahmana is described as a seeker of livelihood and an acceptor of gifts but removable at will. A vaishya is called tribute-paying, meant for being beaten, and to be oppressed at will. The worst position is reserved for the shudras. He is called the servant of another, and to be beaten at will.

Generally the later Vedic texts draw a line of demarcation between the three higher orders on the other hand, and the shudras on the other. There were nevertheless, several public rituals connected with the coronation of the king in which the shudras participated, presumably as survivors of the original Aryan tribe. Certain sections of artisans such as rathkara or chariot-maker enjoyed a high status, and were entitled to the sacred thread ceremony. Therefore even in later Vedic times, Varna distinctions had not advanced very far.

In the family we notice the increasing power of the father, who could even disinherit his son. In princely families the Right of primogeniture was getting stronger. Male ancestors came to be worshipped. Women were generally given a lower position. Although some women theologians took apart in philosophic discussion and some queens participate in coronation rituals ordinarily women were thought to be inferior and suboridinate to men.

The institution of gotra appeared in later Vedic times. Literally it means the cow-pen or the place where cattle belonging to the whole clan are kept, but in course of time it signified descent from a common ancestor. People began to practise gotra exogamy. No marriage could take place between persons belonging to the same gotra or having the same lineage.

Ashramas or four stages of life were not well established in Vedic times. In the post-Vedic texts we hear of four ashramas - that of Brahmachari or student, Grihastha or householder, Vanaprastha or hermit and Sanyasi or ascetic who completely renounced the whole of the worldly life. Only the first three are mentioned in the later Vedic texts; the last or the fourth stage had not been well established in later Vedic times though ascetic life was not unknown. Even in post-Vedic times only the stage of the householder was commonly practiced by all the Varnas.

The two outstanding Rig Vedic gods, Indra and Agni, lost their former importance. On the other hand Prajapati the creator, came to occupy the supreme position in the later Vedic pantheon. Some of the other minor gods of the Rig Vedic period also come to the forefront. Rudra, the god of animals, became important in later Vedic times, and Vishnu came to be conceived as the preserver and protector of the, world, who now led a settled life insteads of a semi-nomadic life as they did in Rig Vedic tiems. In addition, some object began to be worshipped as symbols of divinity; signs of idolatry appear in later Vedic times. As society became divided into social classes, such as brahmanas, rajanyas, vaishyas and shudras, some of the social order comes to have their own deities. Pushan - a Vedic solar deity and one of the Adityas - who was supposed to look after cattle, came to be regarded as the god of the shudras, although in the age of the Rig Veda cattle rearing was the primary occupation of the Aryans.

People worshipped gods for the same material reasons in this period as they did in earlier times. However, the mode of worship changed considerably. Prayers continued to be recited, but they ceased to be the dominant mode of placating the gods. Sacrifices became far more important, and they assumed both public and domestic character. Public sacrifices involved the king and the whole of the community, which was still in the many cases identical with the tribe. Private sacrifices were performed by individuals in their houses because in this period the Vedic people led a settled life and maintained regular households. Individuals offered oblations to Agni, and each one of these took the form of a ritual or sacrifice.

Sacrifices involved the killing of animals on a large scale and, especially the destruction of cattle wealth. The guest was known as goghna or one who was fed on cattle.

Sacrifices were accompanied by formulae which had to be carefully pronounced by the sacrificer. The sacrificer was known as the yajamana, the performer of yajna, and much of his success depended on the magical power of words uttered correctly in the sacrifices. Some rituals performed by the Vedic Aryans are common to the Indo-European peoples, but many rituals seem to have developed on the Indian soil.

These formulae and sacrifices were invented, adopted and elaborated by the priests called the brahmanas. The brahmanas claimed a monopoly of priestly knowledge and expertise. They invented a large number of rituals, some of which were adopted from the non-Aryans. The reason for the invention and elaboration of the rituals is not clear, though mercenary motives cannot be ruled out. We hear that as many as 2,40,000 cows were given as dakshina or gift to the officiating priest in the rajsuya sacrifice.

In addition to cows, which were usually given as sacrificial gifts, gold, cloth and horses were also given. Sometimes the priests claimed portions of territory as dakshina, but the grant of land as sacrificial fee is not well establisned in the later Vedic period. The Satapatha Brahmana states that in the ashvamedha, North, South, East and West all should be given to the priest. If this really happened, then what would remain to the king? This, therefore, merely indicates the desire of the priests to grab as much land as possible. But really considerable transfer of land to priests could not have taken place. There is a reference where land, which was being given to the priests, refused to be transferred to them.

Towards the end of the Vedic period began a strong reaction against priestly domination, against cults and rituals, especially in the land of the Panchalas and Videha where, around 600 B.C., the Upanishads were compiled. These philosophical texts criticized the rituals and laid stress on the value of right belief and knowledge. They emphasized that the knowledge of the self or atman should be acquired and the relation of atman with brahman (the undivided cosmic energy) should be properly understood. Brahma emerged as the supreme entity, comparable to the powerful kings of the Period. Some of the kshatriya princes in Panchala and Videha also cultivated this type of thinking and created the atmosphere for the reform of the priest-dominated religion.

Their teaching promoted the cause of stability and integration. Emphasis on the changelessness, indestructibility and immortality of atman or soul served the cause of stability which was needed for the rising state power headed by the kshatriya raja. Stress on the relation of atman with Brahma fostered allegiance to superior authority.

The later Vedic period saw certain important changes. We find the beginnings of territorial kingdoms. Wars were fought not only for the possession of cattle but also for that of territory. The famous Mahabharata battle, fought between the Kauravas and the Pandavas, is attributed to this period. The predominantly pastoral society of early Vedic times had become agricultural. The tribal pastoralists came to be transformed into peasants who could maintain their chief with frequent tributes. Chiefs grew at the expense of the tribal peasantry, and handsomely rewarded the priests who supported their patrons against the common people called the vaishyas. The shudras were still a small serving order. The tribal society broke up into a varna divided society. But Varna distinctions could not be carried too far. In spite of the support of the brahmanas, the rajanyas or the kshatriyas could not establish a state system. A state cannot be set up without a regular system of taxes and a professional army, which again depends on taxes. But the existing mode of agriculture did not leave scope for taxes and tributes in sufficient measure.

The texts show that the Aryans expanded from Punjab over the whole of Western Uttar Pradesh covered by the Ganges-Yamuna doab (doab nksvkc - is a term used in India and Pakistan for the "tongue," or tract of land lying between two converging, or confluent, rivers). The Bharatas and Purus, the two major tribes, combined and thus formed the Kuru people. In the beginning they lived between the Sarasvati and the Drishadvati just on the fringe of the doab. Soon the Kurus occupied Delhi and the upper portion of the doab, the area called Kurukshetra or the land of the Kurus. Gradually they coalesced with a people called the Panchalas, who occupied the middle portion of the doab. The authority of the Kuru-Panchala people spread over Delhi, and the upper and middle parts of the doab. They set up their capital at Hastinapur situated in the district of Meerut. The history of the Kuru tribe is important for the battle of Bharata, which is the main theme of the great epic called the Mahabharata. This war is supposed to have been fought around 950 B.C. between the Kauravas and the Pandavas, although both of them belonged to the Kuru clan. As a result practically the whole of the Kuru clan was wiped out.

Excavations at Hastinapur, datable to the period 900 B.C. to 500 B.C., have revealed settlements and faint beginnings of town life. But they do not at all answer the description of Hastinapur in the Mahabharata because the epic was finally compiled much later in about the fourth century A.D. when material life had advanced much. In later Vedic times people hardly knew the use of burnt bricks. The mud structures that have been discovered at Hastinapur could not be imposing and lasting. From traditions we learn that Hastinapur was flooded, and the remnants of the Kuru clan moved to Kaushambi near Allahabad.

The Panchala kingdom, which covered the modern districts of Bareilley, Badaun and Farukhabad, is famous for its philosopher kings and Brahmana theologians. Towards the end of the later Vedic period, around 600 B.C., the Vedic people spread from the doab further east to Koshala in eastern Uttar Pradesh and Videha in North Bihar. Although Koshala is associated with the story of Rama, it is not mentioned in Vedic literature. In eastern Uttar Pradesh and North Bihar the Vedic people had to contend against a people who used copper implements and the black-and-red earthern pots. In Western Uttar Pradesh they possibly came up against the people who used pots of ochre or red colour and copper implements. They possibly also encountered thin habitations of some people using black-and-red ware. It is suggested that at a few places they came against the users of the late Harappan culture, but these people seem to represent a conglomerate culture which cannot be characterised as purely Harappan. Whoever be the opponents of the later Vedic peoples evidently they did not occupy any large and compact area and their number in the upper Gangetic basin does not seem to have been large. The Vedic people succeeded in the second phase of their expansion because they used iron weapons and horse-drawn chariots.

5.1 The PGW-Iron Phase Culture and later Vedic economy

From around 1000 B.C. onwards iron was used in the Gandhara area in Pakistan. Iron implements buried with dead bodies have been discovered in good numbers. They have also been found in Baluchistan. At about the same time the use of iron appeared in eastern Punjab, Western Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan. Excavations show that iron weapons such as arrow-heads and spear-heads came to be commonly used in Western Uttar Pradesh from about 800 B.C. onwards. With iron weapons the Vedic people may have defeated the few adversaries that may have faced them in the upper portion of the doab. The iron axe may have been used to clear the forests in the upper Gangetic basin, although because of rainfall ranging between 35 cm to 65 cm these forests may not have been so thick. Towards the end of the Vedic period knowledge of iron spread in eastern Uttar Pradesh and Videha. The earliest iron implements discovered in this area belong to the seventh century B.C., and the metal itself is called shyama or Krishna ayas in the later Vedic texts.

Although very few agricultural tools made of iron have been found, undoubtedly agriculture was the chief means of livelihood of the later Vedic people. Later Vedic texts speak of six, eight, twelve and even twenty-four oxen yoked to the plough. This may be an exaggeration. Ploughing was done woth the help of the wooden ploughshare, which would possibly work in the light soil of the upper gangetic plains. Enough bullocks could not be available because of cattle slaughter in sacrifices. Therefore, agriculture was primitive, but there is no doubt about its wide prevalence. The Satapatha Brahmana speaks at length about the ploughing rituals. According to ancient legends, Janaka - the king of Videha and father of Sita, lent his hand to the plough. In those days even kings and princes did not hesitate to take to manual labour. Balarama, the brother of Krishna, is called haladhar or wielder of the plough. In later times ploughing came to be prohibited for the members of the upper Varnas.

The Vedic people continued to produce barley, but during this period rice and wheat became their chief crops. In subsequent times, wheat became the staple food of the people in Punjab and Western Uttar Pradesh. For the first time the Vedic people came to be acquainted with rice in the doab. It is called vrihi in the Vedic texts, and its remains recovered from Hastinapur belong to the eighth century B.C. The use of rice is recommended in rituals, but that of wheat only rarely. Various kinds of lentils were also produced by the later Vedic people.

The later Vedic period saw the rise of diverse arts and crafts. We hear of smiths and smelters, who had certainly to do something with iron working from about 1000 B.C. Numerous copper tools of the pre 1000 B.C. period found in Western Uttar Pradesh and Bihar might suggest the existence of coppersmiths in both Vedic and non-Vedic societies. The Vedic people may have use the copper mines of Khetri in Rajasthan. In any case copper was one of the first metal to be used by the Vedic people. Copper objects have been found in Painted Grey Ware sites. They were used mainly for war and hunting, and also for ornaments.

Weaving was confined to women but was practised on a wide scale. Leather work, pottery, and carpenter's work made great progress. The later Vedic people were acquainted with four types of pottery-black-and-red ware, black-slipped ware, painted grey ware and red ware. The last type of pottery was most popular with them, and has been found almost all over Western Utter Pradesh. However, the most distinctive pottery of the period is known as Painted Grey ware. It consisted of bowls and dishes, which were used either for rituals or for eating or for both, probably by the emerging upper orders. Glass hoards and bangles found in the PGW layer may have been used as prestige objects by few persons. On the whole both Vedic texts and excavations indicate the cultivation of specialized crafts. Jewel-workers are also mentioned in later Vedic texts, and they possibly catered to the needs of the richer sections of society.

Agriculture and various crafts enabled the later Vedic people to lead a settled life. Excavations and explorations give us some idea about settlements in later Vedic times. Widespread Painted Grey Ware sites are found not only in Western Uttar Pradesh and Delhi, which was the Kuru-Panchala area, but also in the adjoining parts of Punjab and Haryana, which was the Madra area and in those of Rajasthan, which was the Matsya area. Altogether we can count nearly 700 sites, mostly belonging to the upper Gangetic basin. Only a few sites such as Hastinapur, Atranjikhera and Noh have been excavated. Since the thickness of the material remains of habitation ranges from one metre to three metres, it seems that these settlements lasted from one to three centuries. Mostly these were entirely new settlements without having any immediate predecessors. People lived in mudbrick houses or in wattle-and-daub houses erected on wooden poles (wattle and daub is a composite building material used for making walls). Although the structures are poor, ovens and cereals (rice) recovered from the sites show that the Painted Grey Ware people, who seem to be the same as the later Vedic people, were agricultural and led a settled life. But since they cultivated with the wooden ploughshare, the peasants could not produce enough for feeding those who were engaged in other occupations. Hence, peasants could not contribute much to the rise of towns.

Although the term nagara is used in later Vedic texts we can trace only the faint beginnings of towns towards the end of the later Vedic period. Hastinapur and Kaushambi (near Allahabad) can be regarded as primitive towns belonging to the end of the Vedic period. They may be called proto-urban sites. The Vedic texts also refer to the seas and sea voyages. This suggests some kind of commerce which may have been stimulated by the rise of new arts and crafts.

On the whole the later Vedic phase registered a great advance in the material life of the people. The pastoral and semi-nomadic forms of living were relegated to the background. Agriculture became the primary source of livelihood, and life became settled and sedentary. Supplemented by diverse arts and crafts the Vedic people now settled down permanently in the upper Gangetic plains. The peasants living in the plains produced enough to maintain themselves, and they could also spare a marginal part of their produce for the support of chiefs, princes and priests.

5.2 Political organization

In later Vedic times popular assemblies lost importance and royal power increased at their cost. The vidatha completely disappeared. The sabha and samiti continued to hold the ground, but their character changed. They came to be dominated by chiefs and rich nobles. Women were no longer permitted to sit on the sabha, and it was now dominated by nobles and brahmanas.

The formation of wider kingdoms made the chief or the king more powerful. Tribal authority tended to become territorial. Princes ruled over tribes, but their dominant tribes became identical with territories, which might be inhabited by tribes other than their own. In the beginning each area was named after the tribe which settled there first, but eventually the tribal name became current as the territorial name. At first Panchala was the name of a people, and then it became the name of a region. The term rashtra, which indicates territory, first appears in this period.

Traces of the election of the chief or the king appear in later Vedic texts. The one who was considered the best in physical and other qualities was elected raja. He received voluntary presents called bali from his ordinary kinsmen or the common people called the vis. But the chief tried to perpetuate the Right to Receive Presents and enjoy other privileges penaining to his office by making it hereditary in his family; the post generally went to the eldest son. However, this succession was not always smooth. The Mahabharata tells us that Duryodhana, the younger cousin of Yudhishthira, usurped power. For the sake of territory the families of the Pandavas and Kauravas practically destroyed themselves. The Bharata battle shows that kingship knows no kinship.

The king's influence was strengthened by rituals. He performed the rajasuya sacrifice, which was supposed to confer supreme power on him. He performed the ashvamedha, which meant unquestioned control over an area in which the royal horse ran uninterrupted. He also performed the vajapeya or the chariot race, in which the royal chariot was made to win the race against his kinsmen. All these rituals impressed the people with the increasing power and prestige of the king.

During this period collection of taxes and tributes seems to have become common. They were probably deposited with an officer called sangrihitri. The epics tell us that at the time of big sacrifices large-scale distributions were made by the princes and all sections of people were fed sumptuously. In the discharge of his duties the king was assisted by the priest, the commander, the chief queen and a few other high functionaries. At the lower level, the administration was possibly carried on by village assemblies, which may have been controlled by the chiefs of the dominant clans. These assemblies also tried local cases. But even in later Vedic times the king did not possess a standing aimy. Tribal units were mustered in times of war, and according to one ritual for success in war, the king had to eat along with his people (vis) from the same plate.

5.3 Social organisation

The later Vedic society came to be divided into four Varnas called the brahmanas, rajanyas or kshatriyas, vaishyas and shudras. The growing cult of sacrifices enormously added to the power of the brahmanas. In the beginning the brahmanas were only one of the sixteen classes of priests, but they gradually overshadowed the other priestly groups and emerged as the most important class. They conducted rituals and sacrifices for their clients and for themselves, and also officiated at the festivals associated with agricultural operations. They prayed for the success of their patron in war, and in return the king pledged not to do any harm to them. Sometimes the brahmanas came into conflict with the rajanyas, who represented the order of the warrior-nobles, for positions of supremacy. But when the two upper orders had to deal with the lower orders they made up their differences. From the end of the later Vedic period on it began to be emphasised that the two should cooperate to rule over the rest of society.

The vaishyas constituted the common people, and they were assigned to do the producing functions such as agriculture, cattle-breeding, etc. Some of them also worked as artisans. Towards the end of the Vedic period they began to engage in trade. The vaishyas appear to be the only tribute-payers in later Vedic times, and the kshatriyas are represented as living on the tributes collected from the vaishyas. The process of subjugating the mass of the tribesmen to the position of tribute-payers was long and protracted. We have several rituals prescribed for making the refractory people (vis or vaishya) submissive to the prince (raja) and to his close kinsmen called the rajanyas. This was done with the help of the priests who also fattened at the cost of people or the vaishyas. All the three higher varnas shared one common feature-they were entitled to upanayana or investiture with the sacred thread according to the Vedic mantras. The fourth varna was deprived of the sacred thread ceremony, and with this began the imposition of disabilities on the shudras.

The prince, who represented the rajanya order, tried to assert his power over all the three other varna. According to the Aitareya Brahmana, a text of the later Vedic period, in relation to the prince, the brahmana is described as a seeker of livelihood and an acceptor of gifts but removable at will. A vaishya is called tribute-paying, meant for being beaten, and to be oppressed at will. The worst position is reserved for the shudras. He is called the servant of another, and to be beaten at will.

Generally the later Vedic texts draw a line of demarcation between the three higher orders on the other hand, and the shudras on the other. There were nevertheless, several public rituals connected with the coronation of the king in which the shudras participated, presumably as survivors of the original Aryan tribe. Certain sections of artisans such as rathkara or chariot-maker enjoyed a high status, and were entitled to the sacred thread ceremony. Therefore even in later Vedic times, Varna distinctions had not advanced very far.

In the family we notice the increasing power of the father, who could even disinherit his son. In princely families the Right of primogeniture was getting stronger. Male ancestors came to be worshipped. Women were generally given a lower position. Although some women theologians took apart in philosophic discussion and some queens participate in coronation rituals ordinarily women were thought to be inferior and suboridinate to men.

The institution of gotra appeared in later Vedic times. Literally it means the cow-pen or the place where cattle belonging to the whole clan are kept, but in course of time it signified descent from a common ancestor. People began to practise gotra exogamy. No marriage could take place between persons belonging to the same gotra or having the same lineage.

Ashramas or four stages of life were not well established in Vedic times. In the post-Vedic texts we hear of four ashramas - that of Brahmachari or student, Grihastha or householder, Vanaprastha or hermit and Sanyasi or ascetic who completely renounced the whole of the worldly life. Only the first three are mentioned in the later Vedic texts; the last or the fourth stage had not been well established in later Vedic times though ascetic life was not unknown. Even in post-Vedic times only the stage of the householder was commonly practiced by all the Varnas.

6.0 Gods, Rituals and philosophy

In the later Vedic period the upper doab developed to be the cradle of Aryan culture under brahminical influence. The whole of the Vedic literature seems to have been compiled in this area in the land of the Kuru-Panchalas. The cult of sacrifice central to this was accompanied by rituals and formulae.

The two outstanding Rig Vedic gods, Indra and Agni, lost their former importance. On the other hand Prajapati the creator, came to occupy the supreme position in the later Vedic pantheon. Some of the other minor gods of the Rig Vedic period also come to the forefront. Rudra, the god of animals, became important in later Vedic times, and Vishnu came to be conceived as the preserver and protector of the, world, who now led a settled life insteads of a semi-nomadic life as they did in Rig Vedic tiems. In addition, some object began to be worshipped as symbols of divinity; signs of idolatry appear in later Vedic times. As society became divided into social classes, such as brahmanas, rajanyas, vaishyas and shudras, some of the social order comes to have their own deities. Pushan - a Vedic solar deity and one of the Adityas - who was supposed to look after cattle, came to be regarded as the god of the shudras, although in the age of the Rig Veda cattle rearing was the primary occupation of the Aryans.

People worshipped gods for the same material reasons in this period as they did in earlier times. However, the mode of worship changed considerably. Prayers continued to be recited, but they ceased to be the dominant mode of placating the gods. Sacrifices became far more important, and they assumed both public and domestic character. Public sacrifices involved the king and the whole of the community, which was still in the many cases identical with the tribe. Private sacrifices were performed by individuals in their houses because in this period the Vedic people led a settled life and maintained regular households. Individuals offered oblations to Agni, and each one of these took the form of a ritual or sacrifice.

Sacrifices involved the killing of animals on a large scale and, especially the destruction of cattle wealth. The guest was known as goghna or one who was fed on cattle.

Sacrifices were accompanied by formulae which had to be carefully pronounced by the sacrificer. The sacrificer was known as the yajamana, the performer of yajna, and much of his success depended on the magical power of words uttered correctly in the sacrifices. Some rituals performed by the Vedic Aryans are common to the Indo-European peoples, but many rituals seem to have developed on the Indian soil.

These formulae and sacrifices were invented, adopted and elaborated by the priests called the brahmanas. The brahmanas claimed a monopoly of priestly knowledge and expertise. They invented a large number of rituals, some of which were adopted from the non-Aryans. The reason for the invention and elaboration of the rituals is not clear, though mercenary motives cannot be ruled out. We hear that as many as 2,40,000 cows were given as dakshina or gift to the officiating priest in the rajsuya sacrifice.

In addition to cows, which were usually given as sacrificial gifts, gold, cloth and horses were also given. Sometimes the priests claimed portions of territory as dakshina, but the grant of land as sacrificial fee is not well establisned in the later Vedic period. The Satapatha Brahmana states that in the ashvamedha, North, South, East and West all should be given to the priest. If this really happened, then what would remain to the king? This, therefore, merely indicates the desire of the priests to grab as much land as possible. But really considerable transfer of land to priests could not have taken place. There is a reference where land, which was being given to the priests, refused to be transferred to them.

Towards the end of the Vedic period began a strong reaction against priestly domination, against cults and rituals, especially in the land of the Panchalas and Videha where, around 600 B.C., the Upanishads were compiled. These philosophical texts criticized the rituals and laid stress on the value of right belief and knowledge. They emphasized that the knowledge of the self or atman should be acquired and the relation of atman with brahman (the undivided cosmic energy) should be properly understood. Brahma emerged as the supreme entity, comparable to the powerful kings of the Period. Some of the kshatriya princes in Panchala and Videha also cultivated this type of thinking and created the atmosphere for the reform of the priest-dominated religion.

Their teaching promoted the cause of stability and integration. Emphasis on the changelessness, indestructibility and immortality of atman or soul served the cause of stability which was needed for the rising state power headed by the kshatriya raja. Stress on the relation of atman with Brahma fostered allegiance to superior authority.

The later Vedic period saw certain important changes. We find the beginnings of territorial kingdoms. Wars were fought not only for the possession of cattle but also for that of territory. The famous Mahabharata battle, fought between the Kauravas and the Pandavas, is attributed to this period. The predominantly pastoral society of early Vedic times had become agricultural. The tribal pastoralists came to be transformed into peasants who could maintain their chief with frequent tributes. Chiefs grew at the expense of the tribal peasantry, and handsomely rewarded the priests who supported their patrons against the common people called the vaishyas. The shudras were still a small serving order. The tribal society broke up into a varna divided society. But Varna distinctions could not be carried too far. In spite of the support of the brahmanas, the rajanyas or the kshatriyas could not establish a state system. A state cannot be set up without a regular system of taxes and a professional army, which again depends on taxes. But the existing mode of agriculture did not leave scope for taxes and tributes in sufficient measure.