Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - being learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

The Post Maurya Period - Part 1

1.0 Introduction

The period which began in about 200 B.C. did not witness a large empire like that of the Mauryas, but it is notable for intimate and widespread contacts between Central Asia and India. In eastern India, central India and the Deccan, the Mauryas were succeeded by a number of native rulers such as the Shungas, the Kanvas and the Satavahanas. In north-western India ,they were succeeded by a number of ruling dynasties from Central Asia. This makes the study of this part of ancient Indian history multi-layered, and interesting.

2.0 The Indo-Greeks

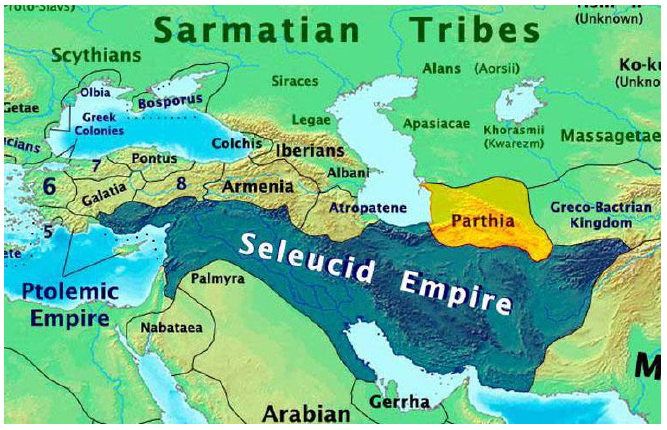

A series of invasions began in about 200 B.C. The first to cross the Hindukush were the Greeks, who ruled Bactria, lying south of the Oxus river in the area covered by north Afghanistan. The invaders came one after another, but some of them ruled at one and the same time. One important cause of invasions was the weakness of the Seleucid Empire, which had been established in Bactria and the adjoining areas of Iran called Parthia. On account of growing pressure from the Scythian tribes, the later Greek rulers were unable to hold their power in this area. With the construction of the Chinese Wall, the Scythians were now pushed back from the Chinese borders. So they turned their attention towards the neighbouring Greeks and Parthians. Pushed by the Scythian tribes, the Bactrian Greeks were forced to invade India. The successors of Ashoka were too weak to stem the tide of foreign invasions which started during the period.

The first to invade India were the Greeks, who are called the Indo-Greeks or Bactrian Greeks. In the beginning of the second century B.C. the Indo-Greeks occupied a large part of north-western India, much larger than that conquered by Alexander. It is said that they pushed forward as far as Ayodhya and Pataliputra. But the Greeks failed to establish united rule in India. Two Greek dynasties ruled north-western India on parallel lines at one and the same time. The most famous Indo-Greek ruler was Menander (165-145 B.C.). He is also known by the name Milinda. He had his capital at Sakala (modern Sialkot) in Punjab; and he invaded the Ganga-Yamuna doab. He was converted to Buddhism by Nagasena, who is also known as Nagarjuna. Menander asked Nagasena many questions relating to Buddhism. These questions and Nagasena's answers were recorded in the form of a book known as Milinda Panho or The Questions of Milinda.

The Indo-Bactrian rule is important in the history of India because of the large number of coins which the Greeks issued. The Indo Greeks were the first rulers in India to issue coins which can be definitely attributed to the kings. This is not possible in the case of the early punch-marked coins, which cannot be assigned with certainty to any dynasty. The Indo-Greeks were the first to issue gold coins in India, which increased in number under the Kushans. The Greek rule introduced features of Hellenistic art in the north-west frontier of India. This art was the outcome of the Greek contest with non-Greek conquered peoples after Alexander's death. Gandhara art was its best example in India.

3.0 The Shakas

The Greeks were followed by the Shakas, who controlled a much larger part of India than the Greeks did. There were five branches of the Shakas with their seats of power in different parts of India and Afghanistan. One branch of the Shakas settled in Afghanistan. The second branch settled in Punjab with Taxila as its capital. The third branch settled in Mathura, where it ruled for about two centuries. The fourth branch established its hold over Western India, where the Shakas continued to rule until the fourth century A.D. The fifth branch of the Shakas established its power in the upper Deccan.

The Shakas did not meet much effective resistance from the rulers and peoples of India. In about 58 B.C. we hear of a king of Ujjain who effectively fought against the Shakas and succeeded in driving them out in his time. He called himself Vikramaditya, and an era called the Vikrama Samvat is reckoned from the event of his victory over the Shakas in 57 B.C. From this time onwards, Vikramaditya became a coveted title. Whoever achieved anything great adopted this title just as the Roman emperors adopted the title of Caesar in order to emphasize their great power. As a result of this practice we have as many as 14 Vikramadityas in Indian history, and the title continued to be fashionable with the Indian kings till the twelfth century A.D., and it was especially prevalent in Western India and the Western Deccan.

Although the Shakas established their rule in different parts of the country, only those who ruled in Western India held power for any considerable length of time, for about four centuries or so. The most famous Shaka ruler in India was Rudradaman (A.D. 130-150). He ruled not only over Sindh, but also over a good part of Gujarat, Konkan, the Narmada valley, Malwaand Kathiawar. He is famous in history because of the repairs he undertook to improve the Sudarshana lake in the semiarid zone of Kathiawar. This lake had been in use for irrigation for a long time, and was as old as the time of the Mauryas.

Rudradaman was a great lover of Sanskrit. Although a foreigner settled in India, he issued the first-ever long inscription in chaste Sanskrit. All the earlier longer inscriptions that we have in this country were composed in Prakrit.

4.0 The Parthians

The Shaka domination in north-western India was followed by that of the Parthians, and in many ancient Indian Sanskrit texts the two peoples are together mentioned as Shaka Pahlavas. In fact they ruled over this country on parallel lines for some time. Originally the Panhians lived in Iran, from where they moved to India. In comparison with the Greeks and the Shakas they occupied only a small portion of north-western India in the first century. The most famous Parthian king was Gondophernes, in whose reign St. Thomas is said to have come to India for the propagation of Christianity. In course of time, the Parthians like the Shakas before them became an integral part of Indian polity and society.

5.0 The Kushans

The Parthians were followed by the Kushans, who are also called Yuechis or Tocharians. The Kushans were one of the five clans into which the Yuechi tribe was divided. The Kushans were nomadic people from the steppes of North Central Asia living in the neighbourhood of China. They first occupied Bactria or North Afghanistan where they displaced the Shakas. Gradually they moved to the Kabul valley and seized Gandhara by crossing the Hindukush, replacing the rule of the Greeks and Parthians in these areas. Finally they set up their authority over the lower Indus basin and the greater part of the Gangetic basin, Their Empire extended from the Oxus to the Ganga, from Khorasan in Central Asia to Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh. A good part of Central Asia later included in the (now defunct) USSR, a portion of Iran, a portion of Afghanistan, almost the whole of Pakistan, and almost the whole of Northern India were brought under one rule by the Kushans. This created a unique opportunity for the commingling of peoples and cultures, and the process gave rise to a new type of culture which embraced five modern countries.

We come across two successive dynasties of the Kushans. The first dynasty was founded by a house of chiefs who were called Kadphises and who ruled for 28 years from about A.D. 50. It had two kings. The first was Kadphises who issued coins south of the Hindukush. He minted coppers in imitation of Roman coins. The second king was Kadphises II, who issued a large number of gold money and spread his kingdom east of the Indus.

The house of Kadphises was succeeded by that of Kanishka. Its kings extended the Kushan power over upper India and the lower Indus basin. The early Kushan kings issued numerous gold coins with higher degree of metallic purity than is found in the Gupta gold coins. Although the gold coins of the Kushans are found mainly west of the Indus, their inscriptions are distributed not only in north-western India and Sindh but also in Mathura, Stnvasti, Kaushambi and Varanasi. Hence they had set up their authority in the greater part of the Gangetic basin. Kushan coins, inscriptions, constructions and pieces of sculpture found in Mathura show that it was their second capital in India, the first being Purushapura or Peshawar, where Kanishka erected a monastery and a huge stupa or relic tower which excited the wonder of foreign travellers.

5.1 Kanishka

Kanishka was a king of the Kushana Empire in South Asia. He was famous for his military, political and spiritual achievements, and along with Ashoka and Harshavardhana is considered to be the greatest king by Buddhists. He had a vast empire, it extended from Oxus in the East to Varanasi in the West, and from Kashmir in the North to the coast of Gujarat including Malwa in the South. The date of his accession to the throne is not certain, but is believed to be 78 AD. This year marks the beginning of an era, which is known as the Shaka era. Under the reign of Kanishka, Kushana dynasty reached the zenith of its power and became the mighty empire in the world.

Kanishka was tolerant towards all the religions.He issued many coins during his rule. His coins depict Hindu, Buddhist, Greek, Persian and Sumerian-Elemite images of gods, showing his secular religious policy. He is remembered for his association with Buddhism. He himself was a Buddhist convert, and convened the fourth Buddhist council in Kashmir. This council in Kashmir marked the beginning of Mahayana cult of Buddhism. He patronized both the Gandhara School of Greco-Buddhist Art and the Mathura School of Hindu Art. He sent Buddhist missionaries to various parts of the world to spread Buddhism. Kanishka is remembered in Buddhist architecture mainly for the multi storey relic tower, enshrining the relics of the Buddha, constructed by him at Peshawar. The Chinese traveler Xuanzang who came to India in seventh century gives the detailed account of this multi storey Stupa. With the expansion of his territories in China he also spread Buddhism there. Various Buddhist theologians such as Vasumitra, Parshva, Sangharaksha and Ashvaghosha are associated with Kanishka. All the patronage given to Buddhism by Kanishka seems to have been political.

Historians are uncertain about the death of Kanishka. Chinese annals tell the story of a Kushana king who was defeated by the General Pan Chao, towards the end of the first century AD, some people believe it to be the King Kanishka.

6.0 Impact on Central Asian Contacts

6.1 Structures and pottery

The Shaka-Kushan phase registered a distinct advance in building activities. Excavations have revealed several layers of construction, sometimes more than half a dozen at various sites in North India. In them we find the use of burnt bricks for flooring and that of tiles for both flooring and roofing. But the use of surkhi and tiles may not have been adopted from outside. The period is also marked by the construction of brick-walls. Its typical pottery is red ware, both plain and polished, with medium to fine fabric. The distinctive pots are sprinklers and spouted channels. They remind us of red pottery with thin fabric found in the same period in Kushan layers in Soviet Central Asia. Red pottery techniques were widely known in Central Asia, and they are found even in regions like Farghana which were on the peripheries of the Kushan cultural zone.

6.2 Better cavalry

The Shakas and Kushans added new ingredients to Indian culture and enriched it immensely. They settled in India for good and completely identified themselves with its culture. Since they did not have their script, written language, or any organized religion, they adopted these components of culture from India. They became an integral part of Indian society to which they contributed considerably. They introduced better cavalry and the use of the riding horse on a large scale. They made common the use of reins and saddles, which appear in the Buddhist sculptures of the second and third centuries A.D. The Shakas and the Kushans were excellent horsemen. Their passionate love for horsemanship is attested by numerous equestrian terracotta figures of Kushan times discovered from Begram in Afghanistan. Some of these foreign horsemen were heavily annoured, and fought with spears and lances.

Possibly they also used some kind of a toe stirrup made of rope which facilitated their movements. The Shakas and Kushans introduced turban, tunic, trousers, and heavy long coat. Even now the Afghans and Panjabis wear turbans, and the sherwani is a successor of the long coat. The Central Asians also brought in cap, helmet and boots which were used by warriors. Because of these advantages they made a clean sweep of their opponents in Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India. Later, when this military technology spread in the country, the dependent princes turned them to good use against their fanner conquerors.

6.3 Trade

The coming of the foreigners established intimate contacts between Central Asia and India. As a result India received a good deal of gold from the Altai mountains in Central Asia. Gold also may have been received by it through trade with the Roman Empire. The Kushans controlled the Silk Route, which started from China and passed through their Empire in Central Asia and Afghanistan to Iran, and Western Asia which fanned part of the Roman Empire in the eastern Mediterranean zone. This route was a source of great income to the Kushans, and they built a large prosperous Empire because of the tolls levied from the traders. It is significant that the Kushans were the first rulers in India to issue gold coins on a wide scale.

6.4 Polity

The Central Asian conquerors imposed their rule on numerous petty native princes. This led to the development of a feudatory organization. The Kushans adopted the pompous title of 'king of kings', which indicates their supermacy over numerous small princes.

The Shakas and the Kushans strengthened the idea of the divine origin of kingship. The Kushan kings were called sons of god. This tide was adopted by the Kushans from ihe Chinese, who called their king the son of heaven. It was used in India naturally to legitimatize the royal authority. The Hindu law-giver Manu asks the people to respect the king even if he is a child, because he is a great god ruling in the form of a human being.

The Kushans also introduced the satrap system of government. The Empire was divided into numerous satrapies, and each satrapy was placed under the rule of a satrap. Some curious practices such as hereditary dual rule, two kings ruling in the same kingdom at one and the same time, were introduced. We fand that father and son ruled jointly at one and the same time. Thus it appears that there was less of centralization under these rulers.

The Greeks also introduced the practice of military governorship. They appointed their governors called strategos. Military governors were necessary to maintain the power of the new rulers over the conquered people.

6.5 New elements in Indian society

The Greeks, the Shakas, the Parthians and the Kushans ultimately lost their identity in India. They became completely Indianized in course of time. Since most of them came as conquerors they were absorbed in Indian society as a warrior class, that is, as the kshatriyas. Their placement in the bralunanical society was explained in a curious way. The law-giver Manu stated that the Shakas and the Parthians were the kshatriyas who had deviated from their duties and fallen in status. In other words, they came to be considered as second-class kshatriyas. In no other period of Ancient Indian history were foreigners assimilated into Indian society on such a large scale as they were in the post-Maurya times.