Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - begin learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

CONCEPT – The Indian monsoon – a comprehensive analysis

Read more on - Polity | Economy | Schemes | S&T | Environment

- A century’s worth of study : Today, almost a quarter of the world – 1.76 billion people – live with the South Asian monsoon. A century of meteorological progress and study means that today the IMD (Indian Meteorologial Department) can say with much more confidence than earlier how fast the summer monsoon will sweep up the nation and how much rain, overall, it will bring. When the monsoon started late in 2019, the reason given by IMD was “Cyclone Vayu” in the Arabian Sea, which upset the flows on which the monsoon depends.

- What is the monsoon : On average the monsoon is a regular wave of rain, rising and falling over the months from June to September. In any given year, though, the smooth wave is overwritten by spikes and troughs, bursts of intense precipitation and weeks of odd dryness, variations known as “vagaries” which science still struggles to grasp. There is a complex structure in space, as well as time.

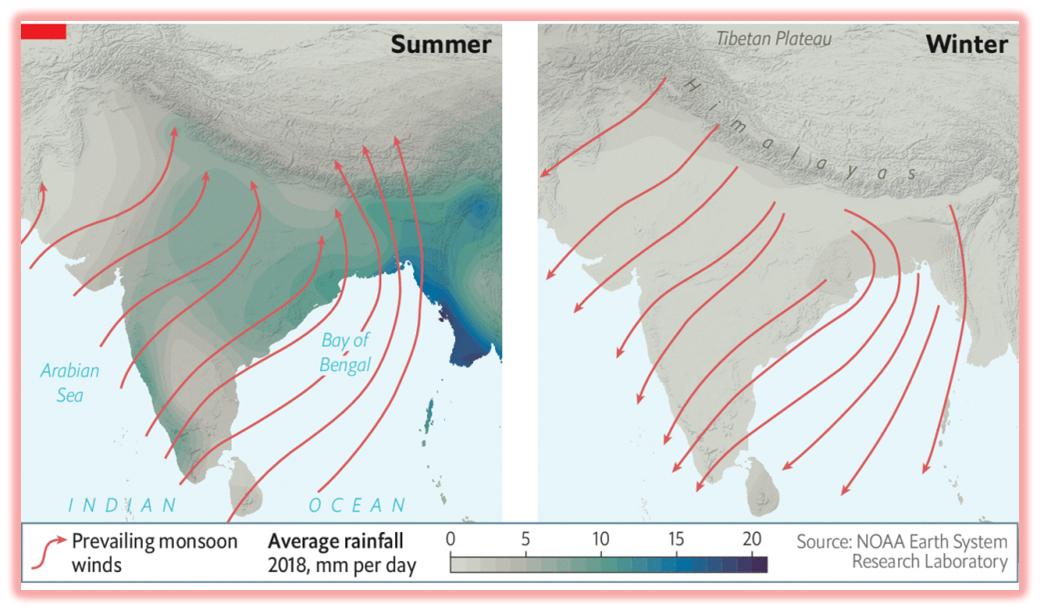

- Understanding its dynamic : The monsoon is something fairly simple: a season-long version of the sea breezes familiar to all those who live by coasts. Because land absorbs heat faster than water does, on a sunny day the land, and the air above it, warm faster than adjoining seas. The hot air rises; the cooler air from above the sea blows in to take its place. A monsoon is the same sort of phenomenon on a continental scale. As winter turns to summer, the Indian subcontinent warms faster than the waters around it. Rising hot air means low pressure; moist maritime water is drawn in to fill the partial void. This moist water, too, rises, and as it does, its water vapour condenses, releasing both water, to fall as rain, and energy to drive further convection, pulling up yet more moist air from below.

- It will only worsen : The flooding that goes with such rains is expected to become worse and wider-spread as the global climate warms. Agriculture remains the Indian economy’s largest source of jobs, directly accounting for a sixth of its GDP and employing almost half of its working people. A bad monsoon can knock Indian economic growth by a third. The effects in Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka are on a similar scale.

- Structural problems : Storage systems in cities have fallen into disuse; aquifers under farmland are depleted year by year faster than the monsoons can refill them. In a country where more people will face the risks of climate change in the decades to come than any other, the problems of the current climate are not being tackled head-on.

- Other global monsoons : There are other monsoonal circulations around the world—in Mexico and the American south-west and in west Africa, as well as in East Asia, to the circulation of which the South Asian monsoon is conjoined.

- Why South Asian monsoon is special : Geography makes the South Asian monsoon particular. The Indian Ocean, unlike the Pacific and the Atlantic, does not stretch up into the Arctic. This means that water warmed in the tropical regions cannot just flow north, taking its heat with it. It stays in the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal, lapping at India from the west and the east. And to the subcontinent’s north sits the Tibetan plateau, the highest on the planet. The summer heat there draws the monsoon’s moisture far higher into the atmosphere than it would otherwise be able to go, adding mountains of cloud to the Himalayan peaks.

- The winds that made Asia : The word “monsoon” blew into English from Portuguese in the late 16th century not because European sailors cared about the rain on alien plains, but because when they followed Vasco da Gama around the tip of Africa they came across a type of wind they had never encountered, and for which they had no name. The Portuguese monção comes in its turn from the Arabic, mawsim, which means “season”. In the Atlantic Ocean, the only one to which the Portuguese were accustomed, winds in any given place tend to blow in pretty much the same direction throughout the year, though their intensities change with the season and their prevailing direction changes with the latitude. In the Indian Ocean, the prevailing winds flip back and forth.

- Role of the ITCZ : The monsoon is deeply affected by the “intertropical convergence zone” (ITCZ) which encircles the world close to the equator. It is a zone of low pressure over the warmest water. In all the oceans, this low pressure draws in steady winds from the south-east known as the southern trade winds. During the northern hemisphere’s winter, the ITCZ sits south of the equator in the Indian Ocean. As warmth creeps north, so does the ITCZ, becoming a dynamic part of the monsoon. It ends up nestled against the Himalayas, bringing the southern trades with it. But their move from the southern hemisphere to the northern, and the constraining effect of high pressure over Africa, sees them twisted from south-easterlies to south-westerlies. When these south-westerly trades pick up in late spring – wind speeds in the Arabian Sea can double over a few weeks – the rains are on their way to Thiruvananthapuram.

- The winter reversal : The monsoons reverse in winter. This is true both for the South Asian monsoon and the East Asian monsoon, which affects Indo-China, the Philippines, southern China, Taiwan, Korea and part of Japan. As the land cools in the autumn, north-easterly winds replace the south-westerlies. Because the winds are mostly dry they are not so important to farmers, though they do bring rain to some parts of southern India. But they matter a great deal to navigation, and thus to human history. The monsoon rains feed what has always been the most populous part of the human world. It is the monsoon winds, though, which brought those people together to form Asia.

- Monsoons shaped Asia : Had sailors, traders and holy men not followed their lead on the monsoon winds, Asia would not be the heterogeneous place it has been through history—and remains today, despite the nationalist narratives and more strictly bordered lives its 20th-century states forced on their newly minted citizens. Tamil merchants from southern India put up inscribed stones in Burma (modern-day Myanmar) and Thailand around the seventh century AD. They seem to have reached the southern Chinese emporium of Canton (Guangzhou) not much later. India’s influence is intense in the extraordinary ninth-century Buddhist temple of Borobudur on Java. Hindu kingdoms arose in the Indonesian archipelago. Bali represents surely the most embellished version of the Hindu faith today. Via India, Islam spread east, too, after Arab merchants carried their faith to the Malabar Coast of south-west India and, eventually, to Quanzhou on China’s eastern seaboard, where 13th-century Muslims lie beneath gravestones inscribed in Arabic. Later, with the Portuguese, Roman Catholicism came to Goa and then, via the south China coast, to Japan.

- Then came the industrial revolution : In the 19th century, with the coming of coal, steam and iron, the Europeans broke with seasonal rhythms, establishing colonial dominance over Asia by means of efficient weaponry and Suez-crossing steamships that could defy the wind to allow a constant flow of raw materials one way—cotton, jute, grain, timber, tin—and returned manufactures the other. The Asian ports established or greatly expanded at the time—Bombay (Mumbai), Calcutta (Kolkata), Madras (Chennai), Batavia (Jakarta), Manila, Shanghai—marked the birth of a fossil-fuel age. The winds were forgotten; but they were not unchanged.

- Global warming : As the build-up of atmospheric greenhouse gases which began back then traps ever more heat the monsoons will change; the vast clouds of pollutants created by Asia’s now endemic use of coal and oil are affecting them too. Ports will be susceptible to sudden flooding and rises in sea level than older, more defensible ports farther up rivers were. The 90 m inhabitants of Asia’s great seaboard cities are among the most vulnerable to the Industrial Revolution’s longest legacy.

- Empires rose and fell : The British were far from the first of the rulers of the Indian subcontinent to transform the hydraulic landscape. The water tank known as the Great Bath of Mohenjo-Daro is part of an urban complex built by rulers of the Indus valley civilisation in the third millennium BC. In 1568 AD Akbar, the third Mughal emperor, had water brought to Delhi not only to “supply the wants of the poor” but also to “leave permanent marks of the greatness of my empire”. He did so by restoring and enlarging a canal to the Yamuna river first cut two centuries earlier by a 14th-century sultan. Akbar’s works, in turn, were restored and re-engineered by the British two and a half centuries later.

- Great famines : In 1876 and 1877, when the summer rains failed completely, India’s administrators invoked the authority of Adam Smith to argue against intervening in the famine which began to spread across the dry land, eventually claiming 5.5 m lives. A couple of years earlier, during a local drought in Bihar, a major catastrophe had been averted through imports of rice from Burma. Yet such expenditure on relief had met with much criticism!

- Amartya Sen : A century later, Amartya Sen, a Nobel-winning economist, argued that what happened in the 1870s was the rule, not the exception: governments are the general cause of famine. Mass starvation is not brought about by a crop-disease- or climate-driven absolute lack of food but by policies and hierarchies which stop people from exchanging their primary “entitlement”, in Mr Sen’s terms—for instance, their labour—for what food there is. Such policies are a feature of autocracies; where the entitlements of the people include real political power, as they do in functioning democracies, they are normally untenable. As a child Mr Sen lived through the Bengal famine of 1943, during which Indians died in the street in front of well-stocked shops guarded by the British state.

- The Great Bengal famile 1943 : That famine, in which up to 3m Bengalis died, followed a devastating cyclone. But much of the damage was done by the scorched-earth policy of colonial officials who, fearing a Japanese invasion, burned the vessels that local cultivators used to ship rice. Britain sent no relief, in part, perhaps, because of Winston Churchill’s active dislike of Indians agitating for independence. Jawaharlal Nehru, who would later become India’s first prime minister, but was at the time imprisoned by the British, wrote from jail “that in any democratic or semi-democratic country, such a calamity would have swept away all the governments concerned with it.”

- ENSO : One of the global climate features impacting Indian monsoon was the “Southern oscillation”. The usual pattern of air pressure over the Pacific features high pressure over Tahiti and low pressure over Darwin, in northern Australia. This dispensation helps drive the trade winds westward the better to feed the monsoon as the intertropical convergence zone sweeps north over India. But a few times a decade a reversal takes place; the pressure that was up goes down, and that which was down goes up. Low pressure over Tahiti and high pressure over Darwin disrupts the trade winds. The South Asian monsoon weakens. In the tropical Pacific the eastern waters, off South America, tend to be cooler than the western ones. Periodically, though, the waters of the east warm while those of the west get cooler. It is this which causes Walker’s seesaw to tip. But the atmosphere in its turn influences the ocean. The strength of the easterly winds in the Pacific is one of the factors that governs distribution of warmth between the east and west. The winds and the oceans operate as a “coupled system”, with heat and momentum shifting from one to the other and back again.

- Coupled system : It has been known as ENSO: EN for El Niño, the name that Peruvians give to warm waters around Christmas time; SO for the Southern oscillation. There are other regular oscillations in the planet’s climate, but ENSO is by far the most important one. When ENSO shifts in the warm-water-off-Peru direction known as its positive phase—as it did, though not very strongly, this past winter—warmth stored in the waters of the Pacific flows into the atmosphere, warming the whole globe. The changes are felt not just in the Pacific and India, but around the tropics and to some extent beyond. When ENSO is in its positive phase, drought can be expected in parts of southern Africa and eastern Brazil, too, while the southern United States can expect things to be wet. In the negative phase—“La Niña”—the situation is largely reversed.

- The Bay of Bengal : The world’s biggest bay has a notable oddity. It boasts a distinct surface layer of light, comparatively fresh water floating atop its deep-sea salinity. This layer is maintained by two things. One is the Brahmaputra, the Ganges and the rest of the lesser rivers, such as the Godavari and the Krishna, that drain most of the subcontinent’s rainfall into the sea to its east. The other is rain that falls onto the bay itself. This fresher water means the top few metres of the bay are much less well mixed than is the norm in oceans—and thus that the sea-surface temperature can vary more quickly. This thermodynamic skittishness is passed on to the air above.

- Bay impacts the vagaries : The bay’s quick changes are the key to the breaks between monsoon rains. Rain falling onto the bay itself cools the surface layer enough to limit the convection that would produce more rain for a while before the surface heats back up again.

- Urban development fails its water : India’s urban development has outrun the wells and rivers. In late June 2019, Chennai, India’s sixth-biggest city, was officially declared to have run out of water. Its municipal authorities blamed the drought. Yet years ago they abandoned any coherent policy of water supply. They allowed developers to fill in the water tanks and seasonal lakes for which the city was once famous. That lack of concern for the city’s future is mirrored everywhere, and India needs a complete reworking of its policy towards water management now.

* Content sourced from free internet sources (publications, PIB site, international sites, etc.). Take your own subscriptions. Copyrights acknowledged.