What went wrong with Ukraine - An insight

Ukraine's desire to join NATO and the E.U. - a dream never fulfilled

Read more on - Polity | Economy | Schemes | S&T | Environment

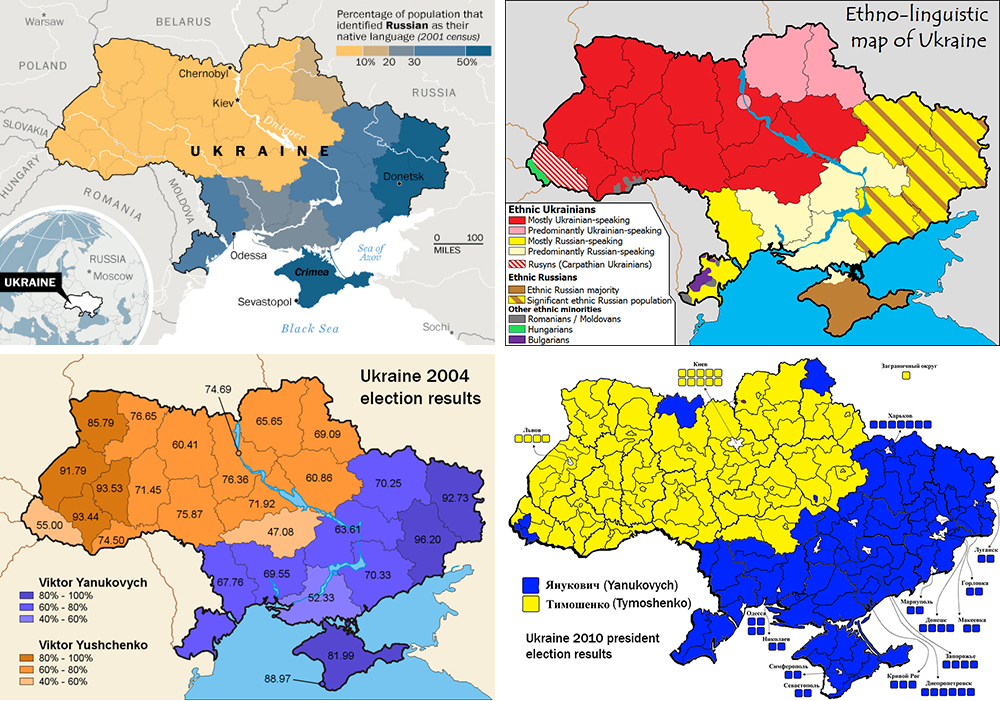

- The story: Even before the threat of a full Russian invasion, Ukraine’s dalliance with the West had cost it dearly. Nearly a decade ago, a civil uprising in Ukraine over President Viktor Yanukovych’s shift toward Moscow and rejection of a sweeping deal with the European Union forced him into exile — but not before the massacre of protesters in Kyiv’s Maidan Square. To punish free-willed Ukrainians, a jilted Russian President Vladimir Putin responded by partitioning their nation, annexing Crimea and staging a de facto occupation of the eastern Donbas region. But still, Ukrainians clung to hope. In 2019, Ukraine even enshrined its will to join the West in its constitution. “Ukraine will join the E.U., Ukraine will join NATO!” declared a jubilant Andriy Parubiy, Ukraine’s speaker of the house, after the measure passed.

- What did the West do: Western powers — even if never in agreement, or fully committed, to letting Ukraine in — dangled the hope of access to those rarefied clubs for years. Now even the distant chance that existed before of Ukraine joining NATO or the E.U. is quickly evaporating.

- U.S. and European leaders stopped short of giving Putin what he has publicly demanded — a firm promise that Ukraine will never join NATO. But they have acknowledged no immediate plans to let Ukraine in, largely citing lingering problems with corruption and a weak rule of law that haven’t helped its case to join the West’s premier clubs. Washington and major European powers have also said they will not send ground forces to defend Ukraine against the Russians — something they would have had to do if Ukraine was part of NATO. The E.U., under the bloc’s rules of collective defense, would have also been bound to respond had Ukraine joined its 27-member union.

- Boxed into an impossible position with neither membership card, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky now edged closer to acknowledging reality. Ukraine’s years-long goal of joining NATO could be little more than “a dream.” The Ukrainian leader was even weighing a possible referendum that could keep his country from joining NATO, acquiescing to a key Putin demand.

- His ruminating underscored the frustration of a nation that has sought to escape the orbit of Russia and grasp for the kind of prosperity witnessed in former Eastern Bloc countries like Poland that joined both the E.U. and NATO. Membership in NATO and the E.U. are two different things; but they were fundamentally similar in purpose: To incorporate Ukrainian into the West.

- NATO and the European Union have been flirting with Kyiv for years. At the 2008 Bucharest, Romania, summit, NATO members promised Ukraine and Georgia membership one day. Former President George W. Bush had championed a more immediate path to entry but was rebuffed by France and Germany. Since then, Russia, by attacking both nations, has sent unambiguous warnings of the cost if they do.

- Ground reality: The failure of either the alliance or the bloc to integrate Ukraine speaks to competing realities. On one hand, NATO and, to a lesser extent the E.U., aims to check Russian power and uphold the principle of national self-determination — that if Ukrainians want a democracy free of Moscow’s interference, they should be allowed to have one. But those lofty goals have been brought down to earth by recognition that the geopolitical realities and the need for a security balance in Europe effectively makes Ukrainian membership impossible as long as Putin sits in the Kremlin.

- American stand: American leaders have been very public in opposition of the idea that autocratic Russia should maintain a sphere of influence in the old Soviet bloc. But some European leaders have seemed to tactically acknowledge Moscow’s case. That was true in 2008. “We are opposed to the entry of Georgia and Ukraine [in NATO] because we think it is not the right response to the balance of power in Europe and between Europe and Russia,” former French Prime Minister François Fillon said then. And it’s still true now. “There is no security for Europeans if there is no security for Russia,” French President Emmanuel Macron said last week after meeting with Putin.

- European stand: The E.U. is known for opening the door to new entrants, only to shut it later: Think Turkey, a country that descended deeper into autocracy and state-sponsored bullying as Brussels dragged its feet on accession talks. NATO — which let in seven Eastern European nations in 2004 — has expanded in recent years to include Montenegro and North Macedonia. But letting in the Ukrainians — who Putin insists are “one people” with Russia — is far more complex.

- A democracy in transit: Ukraine’s still-messy shift to democracy remains a big issue. But the Russian leader’s morphing over the past two decades from mere autocrat to aggressive revanchist is the game changer. In 2004, when the Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia — all former Soviet republics — joined NATO, there were whines and recriminations in Moscow, but no massive troop movements to their borders.

- What’s changed is the thinking of the Russian leadership, which has become much more hostile. The thing Putin is most scared of is having a thriving democratic country with a lot of kinship with Russia right on his border. It would cause enormous problems for him. For his own narrative, for his own security and power base.

- Some argue that the West’s half-embrace of Ukraine has given it false hope, filling it with just enough bravado to keep fighting pro-Russian forces in Donbas, and clamour for the return of Crimea, rather than simply acknowledging the Russian advantage.

- Enough done: But there’s another school of thought that the West has done most of what it can for Ukraine in the geopolitical context, and its decision to refuse Russian demands for a pledge that would definitively end its NATO or E.U. dreams should be hailed. At present, the risk of nuclear war makes military confrontation with Russia on the fields of Eastern Europe a non-starter. But the West has kept a light lit on a distant porch for Ukraine, projecting what could be a far-off possibility of a new future with enough internal change — and in a Putin-free world. With an estimated 1,50,000 of Putin’s troops on Ukraine’s frontier, that future may be getting more and more distant. But until there’s a Russian flag flying over Maidan Square, it may not be dead.

- Summary: Freedom is a choice made by citizens of a country, and eventually only they can take it to the logical conclusion.

- EXAM QUESTIONS: (1) Explain the historical evolution of the Ukraine crisis. Where is it headed now? (2) Why is Russia adamant about keeping Ukraine in its own orbit? Explain. (3) What are the options for the West, as far as the Ukraine crisis is concerned? Explain.