DNA science has revolutionised the study of history

Genetic transfer between France and Britain

Read more on - Polity | Economy | Schemes | S&T | Environment

- The story: History used to be a mysterious subject, to be deciphered from ancient documents, sifting truth from fiction. Not any more. The evidence of history encoded in human DNA has changed the narrative totally.

- Latest research: In 2018, an international research team led in part by Harvard University geneticist David Reich shined a torchlight on one of prehistoric Britain’s murkier mysteries.

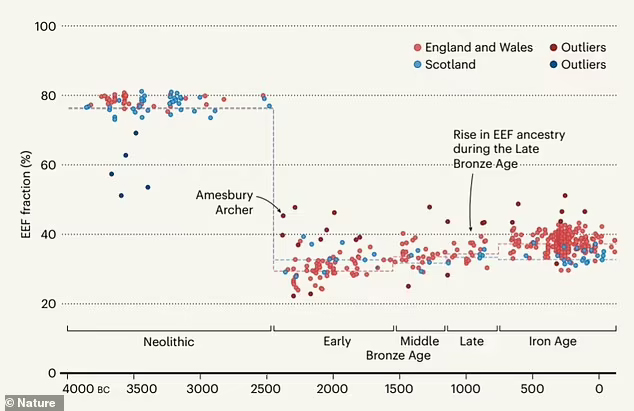

- Analyzing DNA from 793 individuals, the investigators discovered that a massive Late Bronze Age movement displaced around half the ancestry of England and Wales

- By analyzing the degraded DNA from the remains of 400 ancient Europeans, the researchers showed that 4,500 years ago nomadic pastoralists from the steppes on the eastern edge of Europe surged into Central Europe and in some areas their progeny replaced around 75% of the genetic ancestry of the existing populations.

- Descendants of the nomads then moved west into Britain, where they mixed with the Neolithic inhabitants so thoroughly that within a few hundred years the newcomers accounted for more than 90 per cent of the island’s gene pool. In effect, the research suggested, Britain was almost completely repopulated by immigrants.

- Details: According to the findings, from 1,000 BC to 875 BC the ancestry of early European farmers increased in southern Britain but not in northern Britain (now Scotland). The study proposed that this resulted from an influx of foreigners who arrived at this time and over previous centuries, and who — no doubt to the disbelief of 21st-century British nativists — were genetically most similar to ancient inhabitants of France.

- These newcomers accounted for as much as half the genetic makeup of the populace in southern Britain during the Iron Age, which began around 750 BC and lasted until the coming of the Romans in AD 43. DNA evidence from that period led Reich to believe that migration to Britain from continental Europe was negligible.

- Archaeologists had long known about the trade and exchanges across the English Channel during the Middle to Late Bronze Age. But while it was once thought that long-distance mobility was restricted to a few individuals, such as traders or small bands of warriors, the new DNA evidence shows that considerable numbers of people were moving, across the whole spectrum of society.

- Why the study is important: It takes a step back and considers Bronze Age Britain on the macro scale, charting major movements of people over centuries that likely had profound cultural and linguistic consequences. The study demonstrated how, in the past few years, archaeologists and ancient DNA researchers have made great strides in coming together to address questions of interest to archaeologists.

- To a huge extent, this is due to the large ancient DNA sample sizes that it is now possible to generate economically

- Pioneers in the swiftly evolving field of paleogenomics, these experts sequence DNA from ancient skeletal remains and compare it to the genetic material of individuals alive today, piecing together ancient population patterns that traditional archaeological and paleontological methods fail to identify.

- By overturning established theories and conventional wisdoms about migrations following the ice age, they are illuminating the mongrel nature of humanity.

- Troublesome: For all the success of what Reich calls the “genomic ancient DNA revolution” in transforming our understanding of modern humans, the practice of extracting DNA from ancient human remains has raised ethical issues ranging from access to samples to ownership of cultural heritage. Critics point out that in some parts of the world, the very question of who should be considered Indigenous has the potential to fuel nationalism and xenophobia.

- To respond to these concerns, archaeologists, anthropologists, curators and geneticists from 31 countries drafted a set of global standards to handle genetic material, promote data sharing and properly engage Indigenous communities, although the guidelines did little to assuage critics.

- Celtic pride - Since languages “typically spread through movements of people,” the wave of migration was a plausible vector for the diffusion of early Celtic dialects into Britain.

- Everybody agrees that Celtic branched off from the old Indo-European mother tongue as it spread westward, but they have been arguing for years about when and where that branching took place.

- Theory and evidence: For most of the 20th century, the standard theory, “Celtic from the East,” held that the language started around Austria and southern Germany sometime around 750 BC and was taken north and west by Iron Age warriors. An alternative theory, “Celtic from the West,” saw Celtic speakers fanning out from the Atlantic seaboard of Europe, perhaps arising in the Iberian Peninsula or farther north, and settling in Britain by as long ago as 2,500 BC. In 2020, Sims-Williams published a third theory, “Celtic from the Centre,” in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal. His premise was that the Celtic language originated in the general area of France in the Bronze Age, before 1,000 BC, and then spread across the English Channel to Britain in the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age. What is exciting is that, using genetic evidence, science has reached a compatible conclusion.

- The milk of Neolithic kindness: By leveraging the large data set of ancient DNA, scientists found that lactase persistence — the ability of adults to digest the sugar lactose in milk — increased 1,000 years earlier in Britain than in Central Europe. At the dawn of the Iron Age, overall lactase persistence on the island was about 50 per cent, compared with less than 10% in the region stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Adriatic. Analysis of the hardened dental plaque coating ancient teeth, and of traces of fat and protein left on ancient pots, showed that dairy products were a dietary staple in Britain thousands of years before lactase persistence became a common genetic trait. Either Europeans tolerated stomachaches prior to the genetic changes or, perhaps more likely, they consumed processed dairy products like yogurt or cheese where the lactose content has been significantly reduced through fermentation.

- EXAM QUESTIONS: (1) Explain how DNA science is transforming human understanding of history.

* Content sourced from free internet sources (publications, PIB site, international sites, etc.). Take your own subscriptions. Copyrights acknowledged.