Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - begin learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

OILSEEDS IN INDIA

Read more on - Polity | Economy | Schemes | S&T | Environment

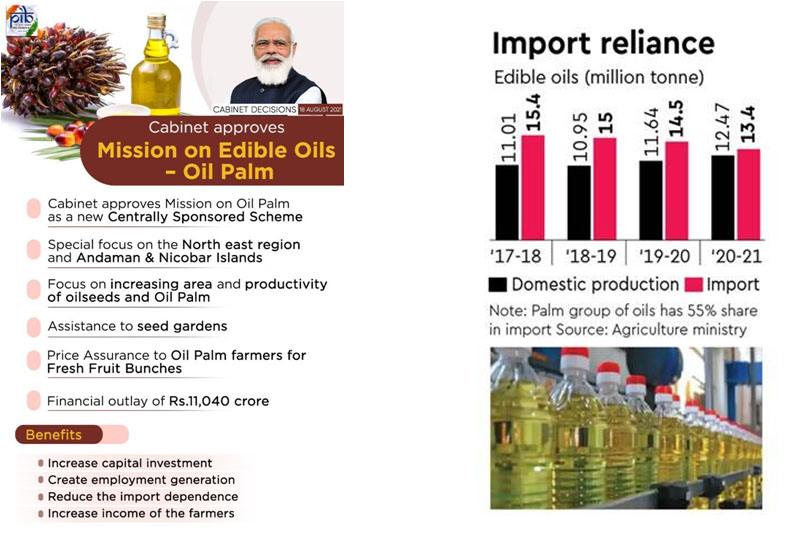

- Oily stuff: Edible oils are consumed heavily in India, and India imports most of the oil it consumes, unlike most other agricultural products which are produced locally. Even after having a diverse agro-climatic conditions, abundant land and large sections of population depending on agriculture, this import burden continues

- Consumption at individual level: Each Indian consumed 19.5 kg of edible oil every year on an average during 2015-16, up from 15.8 kg in 2012-13. This amounts to an aggregate demand of around 26 million tons of edible oils per year. (There are serious health effects of increase in oil consumption and its role on prevalence of lifestyle diseases)

- Primary sources of vegetable oil: Nine oilseeds are the primary source of vegetable oils in the country, which are largely grown under rainfed condition over an area of about 26 million ha. Among these, soybean (34%), groundnut (27%), rapeseed & mustard (27%) contributes to more than 88% of total oilseeds production and >80% of vegetable oil with major share of mustard (35%), soybean (23%) and groundnut (25%).

- Oilseed crops and Field crops: Oilseed crops are the second most important determinant of agricultural economy, next only to cereals within the segment of field crops. The self-sufficiency in oilseeds attained through “Yellow Revolution” during early 1990s, could not be sustained beyond a short period. Despite being the fifth largest oilseed crop producing country in the world, India is also one of the largest importers of vegetable oils today.

- This was launched in the year 1986, for the production of edible oil. Mustards, sesame seeds, etc. were produced to achieve self-reliance, and this came to be known as the Yellow Revolution. The father of the yellow revolution is Sam Pitroda.

- Demand-supply position of edible oils in India: India cultivated oilseeds on 25 million hectare of land, producing 32 million tons of oilseeds in 2018-19, with soybean, rapeseed and mustard and groundnut accounting for almost 90 per cent share in the area

- Assuming a country-wide average of 28 per cent oil recovery, 32 million tons of oilseeds will yield around 8.4 million tons of edible oil. The domestic production can only meet a little over 30 per cent of the total demand for edible oils, necessitating its import

- In 2019, India imported around 15 million tons of edible oils worth approximately Rs 7,300 crore, which accounted for 40 per cent of the agricultural imports bill and three per cent of the overall import bill of the country

- Palm oil accounted for the lion’s share of the total imports (62 per cent), followed by soya oil and sunflower oil (21 per cent and 16 per cent, respectively). There is a considerable increase in the share of soya oil and sunflower oil in the import basket

- The palm oil is primarily sourced from Indonesia and Malaysia, soya oil from Argentina and Brazil, whereas Ukraine and Argentina are the major suppliers of sunflower oils to India

- Apart from a significant burden on the government's exchequer, dependence on the international market for edible oils causes price volatility affecting both the consumers and producers.

- For instance, labour shortage in palm oil plantations of Indonesia and Malaysia, drought in Argentina affecting soyabean production, lower production of sunflower crops in Ukrain and rigorous buying of edible oils by China, impacted price of edible oils in domestic as well as international markets in later part of pandemic year. Subsequently, the government has to reduce import tariff of palm oil by 10 per cent in November to ease the domestic price.

- How to boost domestic production: India has the potential to increase the domestic production of oilseeds which could reduce the import dependence and also benefit the farmers. The government of India is also taking many measures to increase the domestic production of edible oil seeds.

- The Technology Mission on Oilseeds and other policy initiatives have helped India increase the area under oilseeds in India from 9 million tons in 1986 to 32 million tons in 2018-19, though insufficient to meet domestic demand.

- Other initiatives like Oil Palm Area Expansion under Rastriya Krishi Vikas Yojana, increasing the minimum support prices of oilseed crops, creation of buffer stock for oilseeds, cluster demonstration of oilseed crops, etc are being implemented by the government to boost the domestic production.

- Increasing production - 3.6 million tons of additional oils can be produced by means of bridging the yield gap, assuming 1.5 tons per ha as a realizable yield. This requires the wide scale adoption of improved agricultural technologies like quality seeds, optimum use of agro-chemicals and better management.

- Improved varieties like Pusa 12, JS 20-34 of soybean, pusa double zero 30 and 31 of mustard which are low erucic acid as well as high yielding, newer, location specific improved varieties like Kadiri-6, Chattisghar Mungfali 1 (CGM 1) are released for cultivation.

- Farmers need to be made aware about these newer varieties and provided with access to good quality seeds. Cluster demonstrations and other extension activities in this line can be promoted.

- India can also think of expanding the area under oilseed crops by utilising fallow land. India has 11.7 mha of rice fallow, which can be used for the cultivation of safflower and mustard crops, which don’t need much water.

- Alternatives such as rice bran oil is gaining popularity amongst the urban consumers, as it is known to reduce the risk of heart diseases and type 2 diabetes. Rice bran constitutes about 8.5 per cent of the total production of rice and has around 15 % content. Around 2 million tons of edible oil can be produced using the available rice bran.

- Cotton seed is also a promising source of vegetable oil and has an untapped potential. Approximately 1.4 Mt of oil can be augmented with cotton seeds.

- Oil Palms: Another promising non-traditional source of edible oil is ‘oil palms’. Oil palms yield 4 to 5 tons of edible oil per ha, compared to around 1 tons of yield of other traditional oil seeds.

- According to studies, India has the potential to expand the area under oil palm by 1.9 million hectares, which can produce around 7.6 million tons of additional edible oil (Ministry of Agriculture, 2018).

- However, palm oil has a long gestation period, harvesting of the crop is challenging and oil palm is water guzzling crop.

- India has tinkered with tariff rates very frequently in the recent past depending on the demand-supply situation and domestic prices to regulate the imports and to protect the interest of the consumers.

- However, this is a myopic strategy and in the long run, India will gain by having a stable export-import policy. For ensuring proper price signals to increase the domestic production of edible oilseeds, a stable tariff structure is needed.

- A stable and equitable trade policy with clear direction will provide clear price signals for different market stakeholders and boost the domestic production of oilseed crops.

- Oil palm is a widely used commodity that manufacturers need to produce most of the items we use daily. However, in the tropics where it is produced, oil palm contributes to deforestation, loss of biodiversity and disturb the environment. On the one hand, oil palm participates in increasing the wealth of tropical countries, but on the other, this wealth is not well-shared and can create conflicts over land property. Demand for oil palm is expected to increase and therefore will likely cause more deforestation and biodiversity loss. Moreover, oil palm sustainability certifications are not completely respecting their promises to halt deforestation. Consumers can’t really boycott oil palm because millions of people in tropical countries rely on it to make a living, and there are no good alternatives among current vegetable oils.

- Oil palm causes deforestation in the tropics - Oil palm is grown in the tropics which are also a biodiversity hotspot with tropical forests and precious wildlife. Farmers and large private companies cut the forest down, destroying habitats rich in biodiversity, to plant oil palm and make profit.

- Oil palm plantations threaten biodiversity - Tropical forests host many plants and animals, but when oil palm is established, all trees are cut down and animals run away. Oil palm plantations have only one kind of tree, all of the same age and height. In the long term, the species which have lost their habitat are condemned to disappear.

- Oil palm makes ecosystems vulnerable to climate change - From a structurally and biologically diverse forest, the habitat is changed into a monoculture with only oil palms on large areas. The ecosystem completely loses its functions and become vulnerable to weather variation. For example, in Indonesia where peatlands are drained to establish oil palm, floods and fires are more likely to occur. Peatlands are buffer regulating the flow of water falling during rainy days. They act like a sponge, storing the water and slowly releasing it during the dry season. Once peatlands are drained and thereby destroyed, this sponge effect is lost, water flood the area during the rainy season and drought creates fire during the dry season. With a changing climate, such disturbed ecosystems which have lost their biodiversity and regulatory systems are more vulnerable to weather variations.

- Oil palm stores more carbon than alternative crops - Oil palm is not a tree, but it stores carbon almost like a tree. It is better than herbs or grasses to store carbon, but it’s not as good as a perennial tree like rubber. The trunk of oil palms still stores a significant amount of carbon, about half the amount of a primary forest. On a bare and degraded land, it is a great initiative to plant oil palm and therefore increase the amount of carbon stored in the area. However, many oil palm plantations occur at the expense of the forests and peatlands which causes carbon emissions.

- Oil palm contributes to rural development - Oil palm is cultivated in the countryside of tropical countries which are often poor. Rural populations use oil palm as an opportunity to earn more money and make profit with a land often economically idle.

- Oil palm is one of the most profitable land-use in the tropics - The expected increase in oil palm consumption makes it a very good investment. Oil palm is also a very productive plant. When natural conditions and management are optimal, oil palm can produce up to 10 tons per hectare. In Indonesia, the government subsidizes fertilizers and pesticides and promotes oil palm plantations having a high productivity. It makes people rich very fast!

- Oil palm is better than other vegetable oils - In optimum conditions, for example in Indonesia and Malaysia, on average one hectare of oil palm produces 4.5 tons of oil. This is huge compare to other common vegetable oils like rapeseed and soy which produce only 2 tons of oil per hectare. In fact, for a same area, oil palm is the most productive vegetable oil. This high productivity is an opportunity to set apart and preserve some areas for biodiversity.

- Oil palm is widely used in various products - Oil palm is used in a wide range of products spanning from public transport fuel, frozen pizzas and face care creams. We need oil palm and we need a lot of it because it is present in the most commonly used products like cosmetics, food, and fuel. Usually, it composes a small portion of the final product and this complicates the industry’s intent to create a sustainability certification.

- THE WTO PROBLEM IN BOOSTING LOCAL OUTPUT

- Several commodity exporting countries that are either suppliers to, or competitors, to India in the international market have made the World Trade Organisation (WTO) an arena to spar with India.

- The idea is to pressure India into continuing to be a major destination market for their supplies or to blunt India’s competitive edge in export.

- Agricultural commodities in question include pulses and vegetable oils that India imports in sizeable quantities and sugar that India has been exporting in recent years

- In January 2021, during India’s Trade Policy Review meeting, the US and the EU flagged certain trade-related issues including increase in import duties. They also raised certain questions about India’s agricultural support programmes such as the minimum support price for various crops.

- OBJECTIONS RAISED – At the WTO Committee on Agriculture meeting in March 2021, member-countries questioned India on various issues including continued restrictions on pulses import, wheat stockpiling, short-term crop loans, export subsidies for skimmed milk powder and export ban on onions.

- ATTACK ON OILSEEDS PLAN – The latest attack is on India’s ambitious plan to step up domestic oilseeds output so as to reduce dependence on vegetable oil imports which cost roughly $10 billion (about ?75,000 crore) in foreign exchange annually for bringing in 13-14 million tonnes of palm, soybean and sunflower oils.

- WTO member-countries are questioning India mainly regarding incentives to oilseed growers to boost output.

- Two points – (i) they have no business to question, so long as the incentives are well within the permissible limits; (ii) there indeed are ways India can boost domestic oilseeds output even without direct financial incentives or monetary support to growers.

- POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS USING NON-MONETARY TOOLS

- How can India boost domestic oilseed output without direct support?

- Raising the Customs duty on vegetable oil imports is a facile option. It has hardly had any positive impact on domestic oilseeds production in the last 25 years. So, it is not an effective policy instrument.

- Instead of the tariff route, India should look at the trade policy.

- Vegetable oil imports are excessive and speculatively driven. Building large inventory of low-priced imported oils within the country depresses domestic oilseeds prices and discourages oilseed growers. This has been going on for two decades and must be stopped.

- IMPORT CONTRACT REGISTRATION

- As a first step, a system of contract registration and monitoring of imports should be introduced. India already has the system for commodities such as steel and copper. It can be extended to vegetable oils. The government must mandate that all vegetable oil import contracts must be registered with a designated authority.

- Contract details will provide the policymakers critical information such as quantity contracted for, type of oil, origin, price and expected arrival time. This information should become the basis for intervention, if any, needed. Today, the government lacks commercial intelligence and is clueless about forward inbound shipments.

- RESTRICTED CREDIT PERIOD

- Cut importers’ credit period - The second idea relates to imposition of restriction on the ‘credit period’ enjoyed by importers. Overseas suppliers grant 90 to 150 days credit to Indian importers; but the cargo reaches Indian shores in about 10 days (palm oil) or 30 days (soft oils). The Indian importer sells the material immediately and enjoys liquidity for several months during which he indulges in rampant speculation and over-trading before he is required to remit payment. This is leading to a never-ending import cycle.

- Many vegoil importers are actually in an ‘import debt-trap’. To prevent this dangerous debt-trap, the credit period for vegoil import should be restricted to maximum 30 days for palm oil and 45 days for soft oils. This will automatically discourage excessive imports, over-trading and speculation.

- Import contract registration and strict monitoring of import together with restricted credit period will infuse a much needed discipline in the import trade. Reducing speculative and excessive imports of vegetable oil will immediately have a salutary effect on domestic oilseed prices. This is sure to encourage growers to plant more, improve agronomic practices and realise higher yields.

- Indian oilseed production has got trapped at 31-32 million tonnes. To break this stagnation and increase the output by at least two million tonnes a year, should be the goal.

- Price is the best incentive for the grower to stay motivated; and this non-monetary, non-tariff policy initiative (import monitoring and regulation) cannot be faulted by overseas trading partners.

* Content sourced from free internet sources (publications, PIB site, international sites, etc.). Take your own subscriptions. Copyrights acknowledged.