Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - begin learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

GENE DRIVE & BIOTECH 2021

Read more on - Polity | Economy | Schemes | S&T | Environment

- Genetic engineering is, by now, middle-aged. The first genetically engineered bacterium was produced in 1973. This was soon followed by a genetically engineered mouse, in 1974, and a genetically engineered tobacco plant, in 1983.

- The first genetically engineered food approved for human consumption, the Flavr Savr tomato, was introduced in 1994; it proved a disappointment and went out of production a few years later.

- Genetically engineered varieties of corn and soy were developed around the same time; these, by contrast, have become more or less well-accepted.

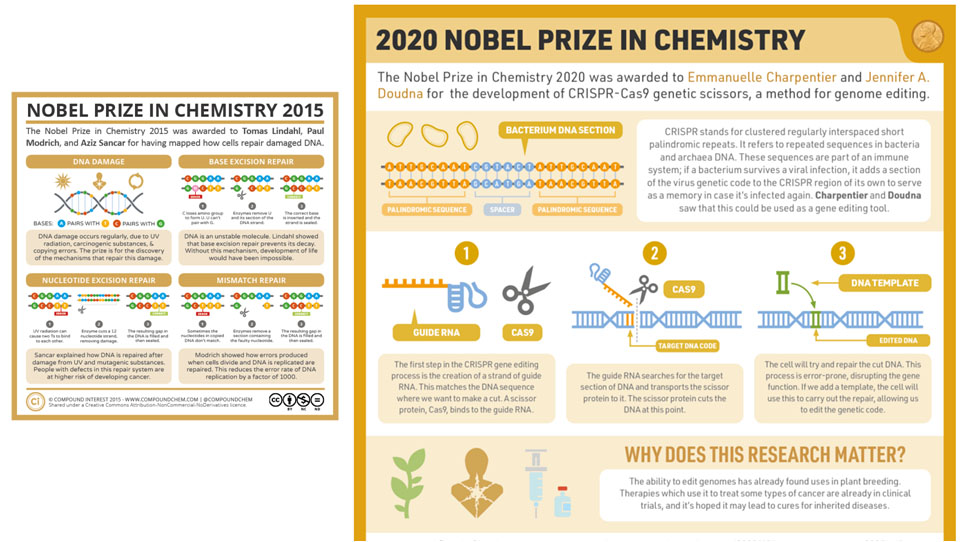

- Since 2010, genetic engineering has undergone a transformation, thanks to CRISPR. This is a suite of techniques, mostly borrowed from bacteria, that make it vastly easier for biohackers and researchers to manipulate DNA.

- CRISPR = acronym for “clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats.” CRISPR allows its users to snip a stretch of DNA and then either disable the affected sequence or replace it with a new one.

- The possibilities that follow are endless, and very dangerous. Jennifer Doudna, one of the developers of CRISPR, says: "we now have “a way to rewrite the very molecules of life any way we wish.""

- With CRISPR, biologists have already created—among many, many other living things—ants that can’t smell, beagles that put on superhero-like brawn, pigs that resist swine fever, macaques that suffer from sleep disorders, coffee beans that contain no caffeine, salmon that don’t lay eggs, and bacteria whose genes contain, in code, a series of photos showing a horse in motion.

- In 2019, a Chinese scientist, He Jiankui, announced that he had produced the world’s first CRISPR-edited humans, twin baby girls. According to He, the girls’ genes had been tweaked to confer resistance to H.I.V., though whether this is actually the case remains unclear. Following his announcement, He was fired from his academic post, in Shenzhen, and sentenced to three years in prison.

- Scientists know that many people are freaked out by genetically modified organisms. They find the idea of eating them repugnant, and of releasing them into the world anathema.

- But actually nature has worked that way. A man looks at a native Australian environment, and sees eucalyptus trees, koalas, kookaburras, whatever. What he is seeing is multiple copies of the eucalyptus genome, multiple copies of the koala genome, and so on. And these genomes are interacting with each other. Then, all of a sudden, the man put an additional genome in there — the cane-toad genome. It was never there before and its interaction is catastrophic.

- Invasive species alter the environment by adding entire creatures that don’t belong. Genetic engineers, by contrast, just alter a few stretches of DNA here and there.

- So the classic thing people tell scientists doing molecular biology is: Are you playing God? Scientists often say that no, we are using our understanding of biological processes to see if we can benefit a system that is in trauma.

- As an example, an invasive species in Australia is the Cane toad. Cane toads are not just disturbingly large; from a human perspective, they’re also ugly, with bony heads and what looks like a leering expression. The trait that makes them truly “hated,” though, is that they’re toxic.

- When an adult is bitten or feels threatened, it releases a milky goo that swims with heart-stopping compounds. Dogs often suffer cane-toad poisoning, the symptoms of which range from frothing at the mouth to cardiac arrest. People who are foolish enough to consume cane toads may die.

- Australia has no poisonous toads of its own; indeed, it has no native toads at all. So its fauna hasn’t evolved to be wary of them. The cane-toad story is thus the Asian-carp story inside out, or maybe upside down. Invasive Asian carp are wreaking havoc in America because nothing eats them; cane toads are a menace in Australia because just about everything eats them.

- The list of species whose numbers have crashed due to cane-toad consumption is long and varied. It includes freshwater crocodiles, which Australians call “freshies”; yellow-spotted monitor lizards, which can grow more than five feet long; northern blue-tongued lizards, which are actually skinks; Australian water dragons, which look like small dinosaurs; common death adders, which, as the name suggests, are venomous snakes; and king brown snakes, which are also venomous. By far the most winning animal on the victims list is the northern quoll, a sweet-looking marsupial.

- Then scientists were brought in. They said - Toxins are generated by metabolic pathways. That means enzymes, and enzymes have to have genes to encode them. So there are tools that can break genes. Maybe humans can break the gene that leads to the toxin. A team at the University of Queensland, recently isolated a crucial enzyme behind the toxin!

- Cane toads store their poison in glands behind their shoulders. In its raw form, the poison is merely sickening. But, when attacked, toads can produce the enzyme that scientists isolated — bufotoxin hydrolase — which amplifies the venom’s potency a hundredfold. Using CRISPR, scientists edited a second batch of embryos to delete a section of the gene that codes for bufotoxin hydrolase. The result was a batch of less toxic toadlets.

- According to the standard version of genetics that kids learn in school, inheritance is a roll of the dice. Let’s say a person (or a toad) has received one version of a gene from his mother—call it A—and a rival version of this gene—A1—from his father. Then any child of his will have even odds of inheriting an A or an A1, and so on. With each new generation, A and A1 will be passed down according to the laws of probability.

- Like much else that’s taught in school, this account is only partly true. There are genes that play by the rules and there are renegades that don’t. Outlaw genes fix the game in their own favor and do so in a variety of devious ways. Some interfere with the replication of a rival gene; others make extra copies of themselves to increase their odds of being passed down; and still others manipulate the process of meiosis, by which eggs and sperm are formed. Such rule-breaking genes are said to “drive.” The most successful driving genes are hard to detect, because they’ve driven other variants to oblivion.

- Since the nineteen-sixties, it’s been a dream of biologists to exploit the power of gene drives—to drive the drive, as it were. Thanks to CRISPR, this dream has now been realized.

- The first mammal to be fitted out with a CRISPR-assisted gene drive will almost certainly be a mouse. Mice are what’s known as a “model organism.” They breed quickly, are easy to raise, and their genome has been intensively studied.

- For the past few decades, the weapon of choice against invasive rodents has been brodifacoum, an anticoagulant that induces internal hemorrhaging. Brodifacoum can be incorporated into bait and then dispensed from feeders, or it can be spread by hand, or dropped from the air. (First you ship a species around the world, then you poison it from helicopters.) Hundreds of uninhabited islands have been demoused and deratted in this way, and such campaigns have helped bring scores of species back from the edge, including New Zealand’s Campbell Island teal, a small, flightless duck, and the Antiguan racer, a grayish lizard-eating snake.

- The downside of brodifacoum, from a rodent’s perspective, is pretty obvious: internal bleeding is a slow and painful way to go. From an ecologist’s perspective, too, there are drawbacks. Non-target animals often take the bait or eat rodents that have eaten it. In this way, poison spreads up and down the food chain. And if just one pregnant mouse survives an application, she can readily repopulate an island.

- Gene-drive mice would scuttle around these problems. Impacts would be targeted. There would be no more bleeding to death. And, perhaps best of all, gene-drive rodents could be released on inhabited islands, where dropping anticoagulants from the air is, understandably, frowned upon.

- To guard against a catastrophe, various fail-safe schemes have been proposed. All of them share a basic, hopeful premise: it should be possible to engineer a gene drive that’s effective but not too effective. Such a drive might be engineered so as to exhaust itself after a few generations.

- The strongest argument for gene editing cane toads, house mice, and ship rats is also the simplest: what’s the alternative? The choice at this point is not between what was and what is but between what is and what will be, which often enough is nothing. This is the situation of the northern quolls, the Campbell Island teal, the Antiguan racer, and the Tristan albatross. Stick to a strict interpretation of the natural and these—along with thousands of other species—are goners. Rejecting gene editing as unnatural isn’t, at this point, going to bring nature back.

- Much closer to realization is an effort to bring back the American chestnut tree. The tree, once common in the eastern U.S., was all but wiped out by chestnut blight. (The blight, a fungal pathogen introduced to North America around 1900, killed off nearly every chestnut on the continent—an estimated four billion trees.) Researchers at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, in Syracuse, New York, have created a genetically modified chestnut that’s immune to blight. The key to its resistance is a gene imported from wheat. Owing to this single borrowed gene, the tree is considered transgenic and cannot be released into the world without federal permits. As a consequence, the blight-resistant saplings are, for now, confined to greenhouses and fenced-in plots.

- The reasoning behind genetic “rescue” is the sort responsible for many a world-altering screwup. The history of biological interventions designed to correct for previous biological interventions is not too motivating.

* Content sourced from free internet sources (publications, PIB site, international sites, etc.). Take your own subscriptions. Copyrights acknowledged.

COMMENTS