Excellent study material for all civil services aspirants - begin learning - Kar ke dikhayenge!

Eight Pacific Island States saving the world’s Tuna

Read more on - Polity | Economy | Schemes | S&T | Environment

- Rich waters, poor nations: They control the richest tuna waters on the planet, an area of the Pacific roughly one-and-a-half times the size of the United States. But 10 years ago, eight island states in whose waters most of the world’s canned tuna is fished were seeing almost none of the profits. In 2011, however, they scored a striking success for small-state diplomacy when they devised a system to raise the fees foreign fleets were paying them for the privilege of fishing in their exclusive economic zones, which extend 200 nautical miles off their coasts. At the time, all they got was a scandalously low fraction of the tuna’s value—as little as 2.5 percent.

- Striking tuna gold: Today, the eight island nations have succeeded beyond their wildest dreams. They increased their take tenfold—from $50 million in 2010 to around $500 million in 2020! Not only did they grow their income, but they also imposed controls that stabilized catch rates and prevented overfishing, a rare success story in a world where ravaging the oceans is still the brutal norm.

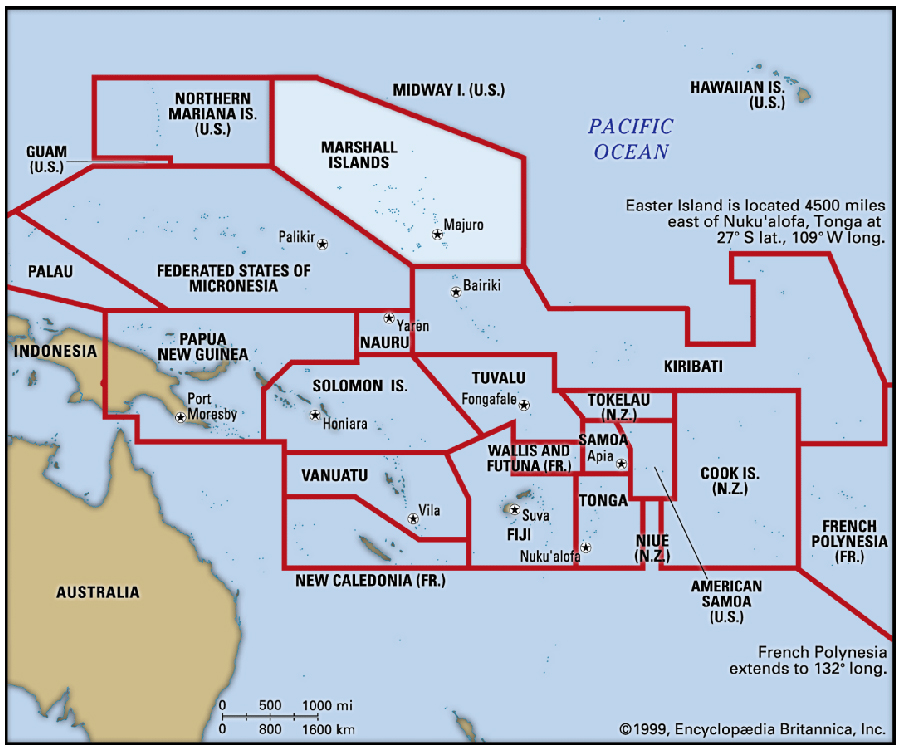

- Description: Six members of the agreement are microstates scattered between the Philippines and Hawaii: Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, Nauru, Palau, and Tuvalu. The other two are much bigger: Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, both closer to Australia. The tuna fees have turned from relatively small change to serious income—and for some of the smaller states, it’s virtually the only non-aid source of foreign exchange. They were therefore highly motivated to make the system sustainable in the long run. For that, they had to make sure the foreign fleets did not do in their waters what they have done almost everywhere else: take too many fish, thereby reducing some populations like the bluefin tuna to 3 percent of their original numbers.

- Small fish taking on the whales: As a result, the group—formally known as the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA)—have become a global model showing how poor, culturally disparate, and isolated small countries can take on the likes of the United States, China, and the European Union—and win. Some are now saying other countries whose waters have been plundered by foreign fleets, such as the nations on West Africa’s coast, should copy the PNA and do the same. Others hope the weak international bodies trying to manage fishing in the Indian, Atlantic, and Eastern Pacific oceans will also emulate them in the decades ahead.

- Tuna fishery of the world: The equatorial belt of the Western and Central Pacific is the single biggest tuna fishery in the world, worth around $6 billion. That’s because half the world’s skipjack tuna—a particularly tasty and prolific species—calls it home. About 1.5 million tons are fished there every year, virtually all of it ending up in cans. Canned tuna is one of the world’s most affordable proteins because it is caught by a method that is both relentlessly efficient and biologically absurd.

- Like most tuna, skipjack—which average under 2 feet long and around 10 pounds—travel in schools. When they come across schools of smaller fish, such as anchovies, they drive them to the surface and gobble them up, attracting seabirds that are then spotted by sharp-eyed ship captains. Fishermen speed to the feeding frenzy and encircle it with huge nets, known as purse seines, that close up at the bottom and are craned into the ship’s hold. The catch is so big that the skipjack at the bottom get crushed, but no one cares because they will end up in small pieces in cans.

- For reasons that are poorly understood, skipjack schools also like to congregate around floating objects—logs, barrels, anything. The purse seiners discovered that setting their nets around these objects yields even bigger catches, sometimes reaching 300 tons of fish at once, according to fisheries scientist John Hampton of the Pacific Community in New Caledonia.

- Using the money wisely: Unlike many other small-country governments that suddenly got an oil bonanza or mining windfall and egregiously wasted or stole it, the PNA countries seem to be spending their bonus’ rather wisely, redistributing much of the new income among their populations. Kiribati: It's a nation of only 117,000 people whose exclusive economic zone is about the size of India and the biggest of the group. The country saw its fishing income rise in the past decade from $27 million in 2008 to $160 million last year—even as it set aside around 11 percent of its EEZ as the Phoenix Islands Protected Area, where it eventually banned all fishing. Kiribati’s extra income “has made a huge difference in the life of the people.

- Summary: The PNA’s example shows that when financial and conservation goals coincide, even the unlikeliest players can score major victories.