Supreme Court appoitments - an analysis

Appointing the Supreme Court judges

Read more on - Polity | Economy | Schemes | S&T | Environment

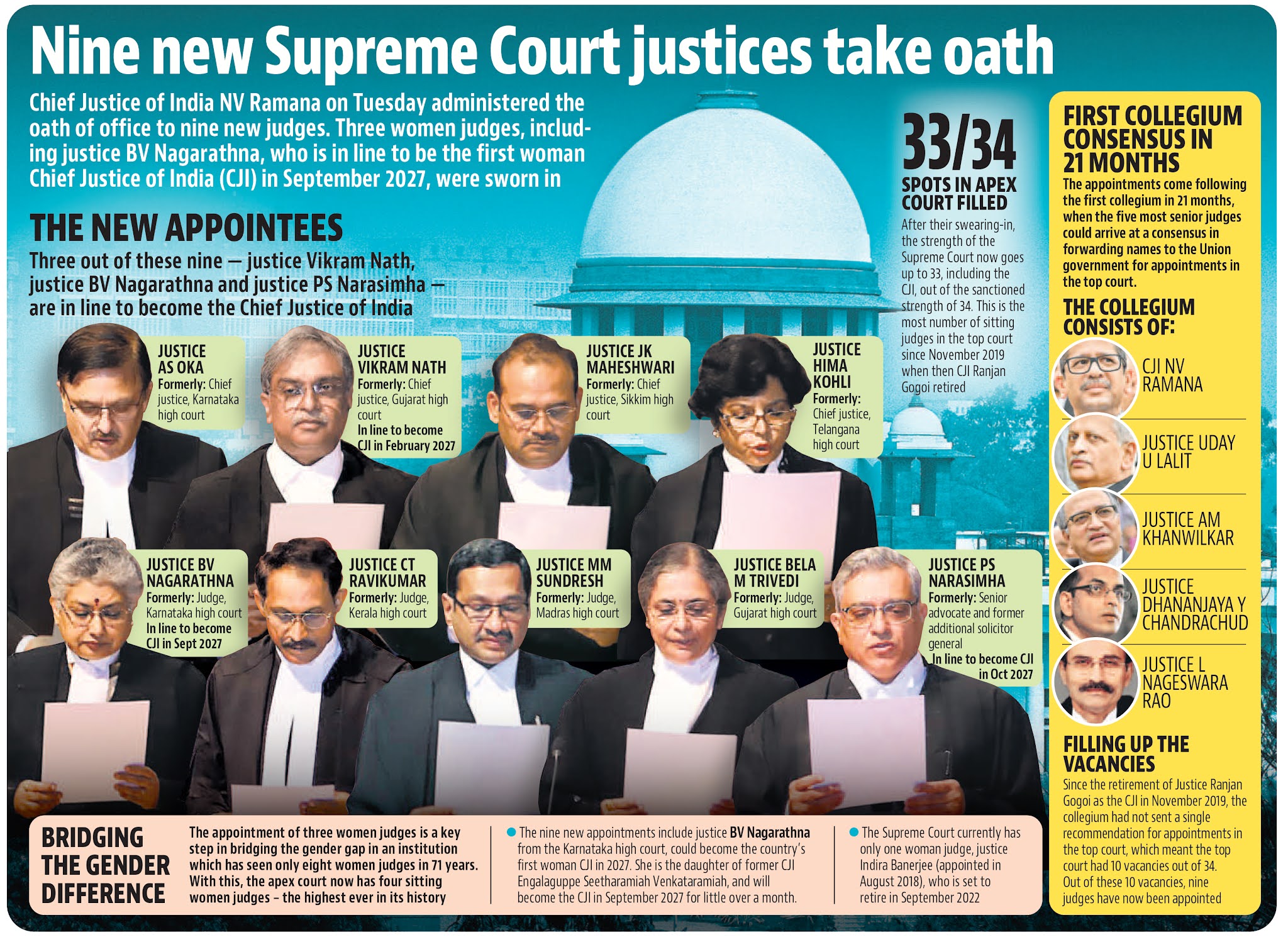

- The story: A record number of judges (nine) took oath at one go, in August 2021, taking the Supreme Court's strength to 33, of whom 4 were women.

- Who appoints SC judges: Articles 124(2) and 217 of the Constitution governs the appointment of judges to the Supreme Court and High Courts respectively.

- The President has the power to make the appointments “after consultation with such of the Judges of the Supreme Court and of the High Courts in the States as the President may deem necessary”.

- Over the years, the word “consultation” has been at the centre of debate on the executive’s power to appoint judges. In practice, the executive held this power since Independence, and a convention of seniority was evolved for appointing the Chief Justice of India.

- This changed from the 1980s as in a series of Supreme Court cases, the judiciary took charge of the power of appointment (for itself).

- The Three Judges cases: The tussle between the executive and the judiciary over judges’ appointment began following the Indira Gandhi-led government’s move in 1973 to supersede three senior judges and appoint Justice A N Ray as the CJI.

- In three cases — which came to be known as the Judges Cases — in 1981, 1993 and 1998, the Supreme Court evolved the collegium system for appointing judges. A group of senior Supreme Court judges headed by the CJI would make recommendations to the President on who should be appointed. These rulings not only shrank the executive say in proposing a candidate for judgeship, but also took away the executive’s veto power.

- In the First Judges Case — S P Gupta v Union of India (1981) — the Supreme Court ruled that the President does not require the “concurrence” of the CJI in appointment of judges. The ruling affirmed the pre-eminence of the executive in making appointments, but was overturned 12 years later in the Second Judges Case.

- In the Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association v Union of India (1993), a nine-judge Constitution Bench evolved the ‘collegium system’ for appointment and transfer of judges in the higher judiciary. The court underlined that the deviation from the text of the Constitution was to guard the independence of the judiciary from the executive and protect its integrity.

- In 1998, President K R Narayanan issued a Presidential Reference to the Supreme Court over the meaning of the term “consultation” — whether it required “consultation” with a number of judges in forming the CJI’s opinion, or whether the CJI’s sole opinion could by itself constitute a “consultation”.

- The ruling on this established a quorum and majority vote in the collegium to make recommendations to the President.

- NJAC: Executive versus Judiciary's tussle isn't new, and in 2014, the NDA government attempted to claw back control on judicial appointments by establishing the National Judicial Appointments Commission through constitutional amendments. Although the law, which gave the executive a greater foot in the door in appointments, had support across political parties, the Supreme Court struck it down as unconstitutional.

- Structure: The Supreme Court has 34 judges including the Chief Justice (CJI). In 1950, when it was established, it had 8 judges including the CJI. Parliament, which has the power to increase the number of judges, has gradually done so by amending the Supreme Court (Number of Judges) Act — from 8 in 1950 to 11 in 1956, 14 in 1960, 18 in 1978, 26 in 1986, 31 in 2009, and 34 in 2019.

- Backlog: In 2019, the Supreme Court was functioning at its full strength of 34. When CJI S A Bobde took over, he inherited just one vacancy, that of his predecessor Ranjan Gogoi. However, the collegium headed by CJI Bobde could not reach a consensus in recommending names, leading to an impasse, that led to accumulation of vacancies, of which now only one remains (until the retirements in 2022).

- What about High Courts: The High Courts on average have over a 30% vacancy. The age of retirement is 65 years for SC judges and 62 for HC judges — unlike in, say, the United States where Supreme Court judges serve for life. Thus means that in India, the process of appointing judges is a continuous one and the collegium system is multi-step process with little accountability on even the timelines that the judiciary has set for itself.

- For High Court appointments, the process is initiated by the HC collegium and the file then moves to the state government, the central government and then to the SC collegium after intelligence reports are gathered on the candidates recommended.

- This often takes over a year. Once the SC collegium clears the names, a delay also happens at the government level for final approval and appointment. If the government wants the collegium to reconsider a recommendation, the file is sent back and the collegium can reiterate or withdraw its decision.

- Has the number of women judges always been low?

- Representation issues: Before latest appointments, Justice Indira Banerjee was the only woman judge in the Supreme Court. Justice B V Nagarathna is in line to become India’s first woman CJI —80 years after Independence. In 1989, justice Fathima Beevi became the first judge to be appointed to the Supreme Court. Since then, however, the SC has had only 11 women judges, inducing the three women appointed recently. But the representation of STs, SCs and OBCs leaves a lot to be desired.

- EXAM QUESTIONS: (1) Explain how power is distributed between the executive and the judiciary, in India. How does it swing from one to the other? (2) What are the three major reasons for judicial pendency in India? How to resolve? (3) What is judicial activism? What is executive encroachment in judicial territory? Explain.

#IndianJudiciary #SupremeCourt #CJI #JudicialAppointments #NJRamana #HighCourts